This post was originally published on this site

Color-coded maps in the 1930s designated predominantly Black and immigrant neighborhoods as too risky to receive New Deal-era government-backed home loans, a practice known as redlining.

Without any fresh investment, buildings in these neighborhoods often fell into disrepair, and housing discrimination played a major role in fueling the racial wealth gap. The typical white family today holds eight times the wealth of a typical Black family and five times the wealth of a typical Hispanic family, according to Federal Reserve data.

In the post-Watergate reform era, Congress tried to reverse redlining through the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which aimed to incentivize banks to invest in and serve the credit needs of poor neighborhoods. Initially, the government turned to a relatively simple method: tracking the number of branches banks operated in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

Yet studies show that redlining continues today.

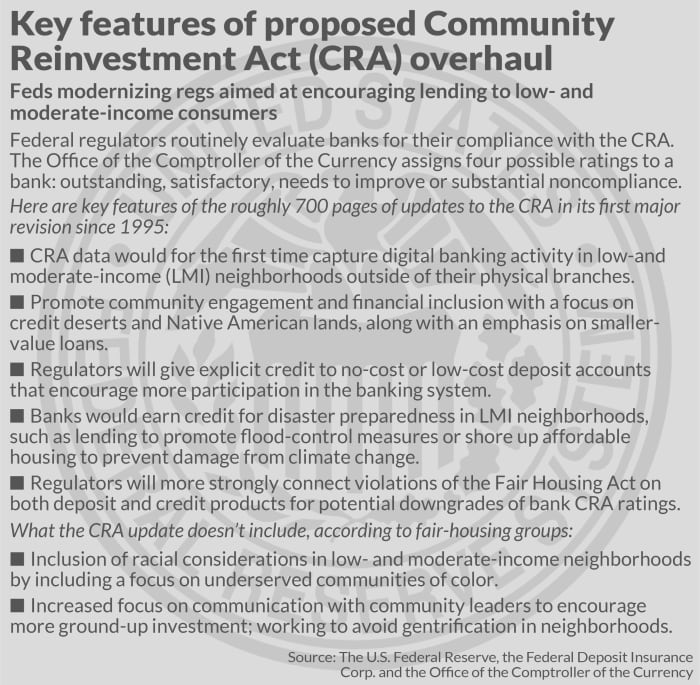

A proposed modernization of the CRA released May 5 would give banks credit for online lending in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods — one basic area that continues to draw support from both sides of the aisle and from the banking industry. The update would also require more disclosure of racial and ethnic data on who gets mortgages, more closely tie any fair-lending infractions by banks to reviews of their CRA compliance, and recognize the role of smaller lenders in helping neighborhoods advance.

See: Effort to bring civil rights era banking law into digital age begins

Some critics, however, say the reform falls short on closing the racial lending gap because it lacks more specific language on addressing underserved communities of color.

Industry groups, social-equity advocates and other stakeholders have begun offering their support and criticisms as regulators work to revise the measure this year.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Concerns from across the political spectrum

The proposed CRA revamp stands out as a major joint effort of the three powerful banking regulatory bodies: the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). But it must still run the gauntlet of a bitterly divided partisan atmosphere in Washington.

“In general, Republicans have concerns that this could be an increased regulatory burden [for banks] without enough of a benefit,” said Ian Katz, an analyst at Capital Alpha Partners.

Reflecting this concern, Michelle Bowman, a community banker appointed by former President Donald Trump to the Fed’s board of governors, said recently there’s no way of knowing “if the costs imposed under the proposal will be greater than the benefits.”

Meanwhile, progressive Democrats want the CRA to do more to increase bank involvement in their communities, Katz said. Democrats also support getting rid of overdraft fees, preventing gentrification in neighborhoods, and doing more to encourage banks to lend to people of color.

Moderates see progress.

David M. Dworkin, the president and CEO of the National Housing Conference, an advocacy group, said the CRA update marks a “significant improvement.”

“This proposed regulation succeeds in improving the clarity and consistency of CRA enforcement for both banks and community advocates, without crossing the line into government credit allocation,” Dworkin said. “It improves the way CRA serves both low- and moderate-income communities and the people who live in them. And it ensures that modernization does not lead to the displacement of the very people it is meant to help.”

Katz said the proposed CRA update is “a bit more rigorous” on the banks than the current version. Banks with $10 billion-plus in assets would be required to share more data with the government on their customer deposits and loans in low- and moderate-income areas, he said.

Banks would also be required to release racial and ethnic data on mortgage borrowers to provide a better window on lending to people of color.

Since the late 1970s, CRA ratings have drawn the most attention when banks try to merge. Critics of bank lending practices to people of color attempted to use a bank’s CRA ratings to block or slow a broad-based move in the industry to consolidate. While such efforts have not stopped industry consolidation, banks still had an incentive to get the highest possible score, said Ed Mills, an analyst at Raymond James.

Banks almost always pass their CRA exams, he added.

“In some ways, the current CRA is like Lake Wobegon, where everyone is above average,” Mills said. “Democrats have been concerned about a certain amount of grade inflation in CRA exams and that the CRA has not been enough of a check on mediocre banks being able to be differentiated from very good banks, especially as they get bigger.”

‘A missed opportunity’ vs. a once-in-a-generation overhaul

Black families comprise 32.6% of homeowners in low-income neighborhoods, but get only 17.4% of bank mortgages, according to data from the Urban Institute, a center-left think tank.

In recent comments, Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard summed up the massive, multi-agency effort to overhaul the CRA as a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

“We believe that the proposal that we put out will strengthen the CRA, make it updated for today’s banking system, today’s communities and the future of banking and the way communities develop,” Brainard said at a June 3 panel discussion hosted by the Urban Institute.

Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard, in front of Fed Chair Jerome Powell.

Bloomberg

The proposed CRA update has drawn praise from fair-housing and other advocates for its efforts to bring the law into the digital age and give more prominence to violations of the federal Fair Housing Act when regulators give banks CRA grades.

But in its current form, the act lacks strong language for improving lending to Black and Latino Americans and other people of color, advocates say. The CRA focuses only on encouraging lending and other financial services to low- and moderate-income people — but research by the Urban Institute has shown that LMI neighborhoods do not highly overlap with neighborhoods of color.

“‘There are provisions … that we think will have the effect of serving communities that have faced systemic inequities.’”

Lisa Rice, the president and CEO of the National Fair Housing Alliance, said the continued focus on income in the CRA update represented “a missed opportunity.” Data shows that high-income Black consumers, Native Americans and other consumers of color lack the same access to credit as low-income white people, she said.

“Just focusing on income is not going to really advance the ball on racial-equity issues,” Rice said. “We thought this rule-making would be an opportunity to really mold the CRA into being an effective tool for advancing racial equity.”

Rice said there’s nothing preventing regulators from including a focus on underserved communities of color, since those groups are a component of the low- to moderate-income neighborhoods targeted in the CRA.

Asked during the panel talk about how the CRA update could ease racial disparities in lending, Brainard said regulators considered the civil-rights spirit of the law to address redlining based on race.

“There are provisions in there that we think will have the effect of serving communities that have faced systemic inequities,” Brainard said.

Some of those measures include collecting already available data to track bank activity in a comparable, consistent way, a practice Brainard said would lead to additional investments in communities of color. The proposed rules also encourage banks to work with smaller businesses with revenues of $250,000 or less and participate in special purpose credit programs, which are lending efforts supported by nonprofits and other advocacy groups.

The new CRA “doubles down” on strengthening its “very strong connection” between Fair Housing Act and fair lending enforcement in CRA exams, Brainard added.

Speaking at the same Urban Institute event, acting FDIC chairman Martin Gruenberg said a proposed CRA mortgage disclosure provision will help regulators shine more light on lending activity to people of color.

“That’ll allow us to look at an institution’s lending in communities of color compared to other communities and compare them to other institutions,” Gruenberg said. “It gives us a line of sight … in the public’s understanding in how these institutions are serving these communities. That’s quite important.”

Power dynamics are key

With Democratic leadership in the White House, the OCC and the FDIC, the CRA overhaul has moved to the front burner. Brainard is leading the effort at the central bank.

When Republicans controlled the White House, former comptroller of the currency Joseph Otting updated the CRA rules in May 2020, but the effort did not receive backing from the Fed or the FDIC and ultimately failed in late 2021, leaving the CRA’s 1995 update in place.

“Because of politicization, there’s a view that you have to have all-Democratic heads or all-Republican to get joint rule-making done,” said Mills, the Raymond James analyst. “Federal banking regulations typically involve a joint process. They work together to develop rules, and any one regulator has veto authority over a regulation being implemented.”

To be sure, the power dynamics in Washington will likely change after this fall’s midterm elections, which are widely expected to benefit the GOP. This potential shift may motivate Biden administration regulators to finalize the new CRA rule before the next Congress takes over in January.

As the proposed rule goes through its final stages in coming months, the banking industry and Republicans are expected to push for objectivity — rules that are as specific as possible to appeal to the lending industry’s meticulous approach to the business. Meanwhile, regulators will want to retain some subjectivity to rules to get banks to do more work to address the spirit of the law.

‘If it works, all the needs will be met’

Former Consumer Bankers Association CEO Richard Hunt said banks currently invest $500 billion a year into all types of communities, and that modernizing the CRA “will give banks more clarity as to which investments will count — allowing them to do more, not less. It will also help ensure CRA investments reach those communities most in need.”

Banks have long called for more clarity and certainty in CRA-eligible activities, as well as equal weight to both branch and non-branch channels and to avoid an “overly strict, one-size-fits-all framework,” Hunt said.

Brian Adkins, senior counsel and a member of the real-estate practice group at the business law firm Buchalter, said in an email to MarketWatch that the CRA update amounts to a well-intentioned effort that could use some refining.

“The CRA has created regulatory burdens and oversight that constrain the market and at the same time have implemented enforcement mechanisms to punish those who are non-compliant, but has not created enough positive reinforcement to incentivize businesses to voluntarily comply,” he said. “I think more effective use of a ‘carrot’ to incentivize private business to balance out the ‘stick’ of various enforcement mechanisms would be essential to making the CRA a long-running success.”

Given that the technological landscape has changed so drastically in recent years, banks now have the potential to use artificial intelligence and other advanced tools to help shape a more equitable society, added Laura Close, an expert on diversity, equity and inclusion and co-founder of the hiring startup Included.ai.

“It’s time for financial institutions and companies to re-examine and up-level their approach to more effective practices that support diversity,” Close said.

The proposed CRA modernization solicits feedback on 180 questions — a sign that regulators remain open to suggestions and answers from interested parties, said Michael Hsu, acting comptroller of the currency.

“If it works, all the needs will be met,” Hsu said at the Urban Institute event. “There would be no redlining. There would be no discrimination. All of the communities, especially for low- and moderate-[income] communities, would be beneficiaries.”