This post was originally published on this site

Legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden in the spring of 2021 was supposed to bring debt relief to socially disadvantaged farmers. A little over a year later, lawsuits blocking the program threaten to accelerate a long-running decline in the number of Black-owned farms.

“It’s leaving people in bad shape,” John Boyd Jr., the founder and president of the National Black Farmers Association, said in a phone interview. “It’s going to wind up leading to more farm foreclosures, especially for Blacks and other farmers of color, because you can’t get access to credit.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture was due last June to begin making debt-relief payments to socially disadvantaged farmers, meaning those belonging to groups that have been subject to racial or ethnic discrimination — part of a $4 billion provision in the sweeping $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. The program was meant to redress decades of discrimination by the federal government, particularly the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and banks.

The debt-relief program, which is held up in the courts, had met immediate resistance from groups of white farmers as well as banks. White farmers argued that the relief amounted to reverse racial discrimination and sued the USDA to block the program. Separately, the early repayment of loans under the program upset banks, which said they were being unjustly deprived of interest payments.

Courts have issued preliminary injunctions blocking the relief.

That’s left qualifying farmers who completed paperwork paving the way for debt forgiveness deeper in debt and struggling as they deal with soaring costs for fuel, fertilizer and other inputs, Boyd said.

“There are folks so concerned that the program won’t be implemented, they’ve already started liquidating assets,” said Dania Davy, the director of land retention and advocacy at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, a nonprofit cooperative association of Black farmers, landowners and cooperatives with members largely across the South.

Many face significant challenges accessing credit because their cash-flow plans had been predicated on getting debt relief, and they were subsequently unable to meet financial metrics for last year as the relief was blocked, Davy said in a phone interview.

An appeals court earlier this year granted the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund a motion to intervene on behalf of Black farmers as they fight a lawsuit in Texas aimed at halting the relief.

Decades of discrimination

The threat posed to Black farm ownership is part of a long-running historical trend. While Black farm ownership rose in the decades after the Civil War brought an end to slavery, the number of Black farmers in the U.S. has fallen sharply and disproportionately over the last century, research shows.

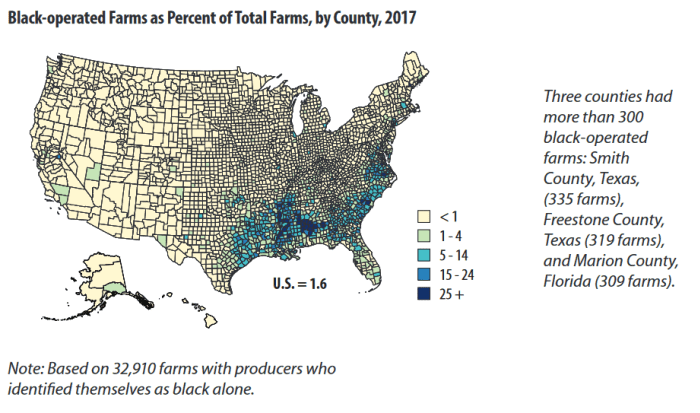

Black farmers owned around 16 million acres by 1910 and accounted for more than 14% of producers. The latest Census of Agriculture in 2017 estimated Black farm ownership at around 4.7 million acres and Black farmers at less than 2% of all farmers.

U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service

Research has shown that decades of discrimination drove a large number of Black farmers off their land. The Agriculture Department acknowledged discriminatory treatment of Black farmers in 1999 and 2011 settlements of lawsuits known as the Pigford cases.

The lawsuits were brought on behalf of Black farmers contending that they had been discriminated against by local USDA county committees when applying for farm loans or attempting to participate in other programs. Discrimination took the form of obstacles to applying for loans and delays in loan approval; Black farmers were also were foreclosed upon more quickly and with less recourse than other producers.

A 2001 investigation by the Associated Press documented a pattern that saw Black Americans cheated out of land or driven off it by intimidation, violence and, in some case, murder. Government officials approved land takings in some cases, and participated in them in others, the reporting found.

Critics argued the Pigford settlements were inadequate. Some farmers have argued that they were shut out of the settlement and that foreclosures against Black-owned farms continued at a disproportionate pace.

‘It’s leaving people in bad shape,’ Boyd says of stalled debt relief.

Courtesy of John Boyd Jr.

The USDA and the Biden administration have faced criticism from Black farm advocates who contend that the relief could have been rolled out more quickly last spring and that more could be done to help tide over producers.

USDA spokespersons didn’t respond to emails or a phone message seeking comment for this article. In June 2021, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack criticized the lawsuits aiming to block the debt relief.

“It’s a wonder where those farmers were over the last 100 years when their Black counterparts were being discriminated against, and didn’t hear a peep from white farmers about how unfortunate that circumstance was,” Vilsack said, according to a news report.

‘Lost opportunity’ to grow intergenerational wealth

The land losses have taken a deep economic toll, according to economists and legal scholars. A paper published last month pegged the present, compounded value of the Black land loss from 1920 to 1997 at roughly $326 billion.

That’s a conservative estimate, said Dania Francis, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston and a co-author of the paper, which argues that had Black families not been intimidated off their farms, they might have invested in more land, which had a high return in the 20th century. Also, data limitations meant the researchers started their estimate in 1920 rather than 1910, which marked the peak of Black land ownership — meaning that a decade of losses wasn’t included in the estimate.

The findings are a springboard to examining neglected causes of the racial wealth gap, Francis said in an interview.

“When I see this amount of wealth being extracted from Black families and Black communities, it represents more than just a dollar figure,” Francis said. “It represents opportunities to spring into the middle class … particularly at a time when the middle class was being formed in the United States and growing.”

“It represents the lost opportunity of growing intergenerational wealth” and helps put the historical origins of the American racial wealth gap into perspective in a way that is not always part of the narrative, which often focuses instead on calls for Black families to save and invest more wisely, Francis said.

Davy said the federation’s legal and other advocacy efforts reflect the fear of a “next wave of Black land loss,” as a program that was intended to bring relief to the community remains blocked.

It’s a threat not only to farmers eligible for debt relief, but is also dissuading young would-be farmers from pursuing production agriculture, Davy said.

“Unfortunately, because of the way the program has not been implemented, it’s actually creating a very poor reputation for both USDA and agricultural production across the rural Black community,” she said.