This post was originally published on this site

In the course of my long career as a financial journalist I have again and again come across things I just wasn’t smart enough to understand.

Back in 1999, for instance, I didn’t understand how internet companies with no profits, revenues or even web traffic could be valued at billions of dollars.

Around 2006 I was baffled at how condos in Las Vegas, probably the least land-constrained city in the world, could sell for twice their cost. And how subprime mortgage baloney could be turned into AAA-grade investment sirloin if you sliced it right.

And not long ago I confess I was confused at why people would pay tens of millions of dollars for something that looked very much like a screenshot from an iPad.

As you can tell, I must be a bit of a dummy because I could never make heads or tails of any of these things.

Here’s something else that’s got me scratching my head. It’s called Medicare Advantage.

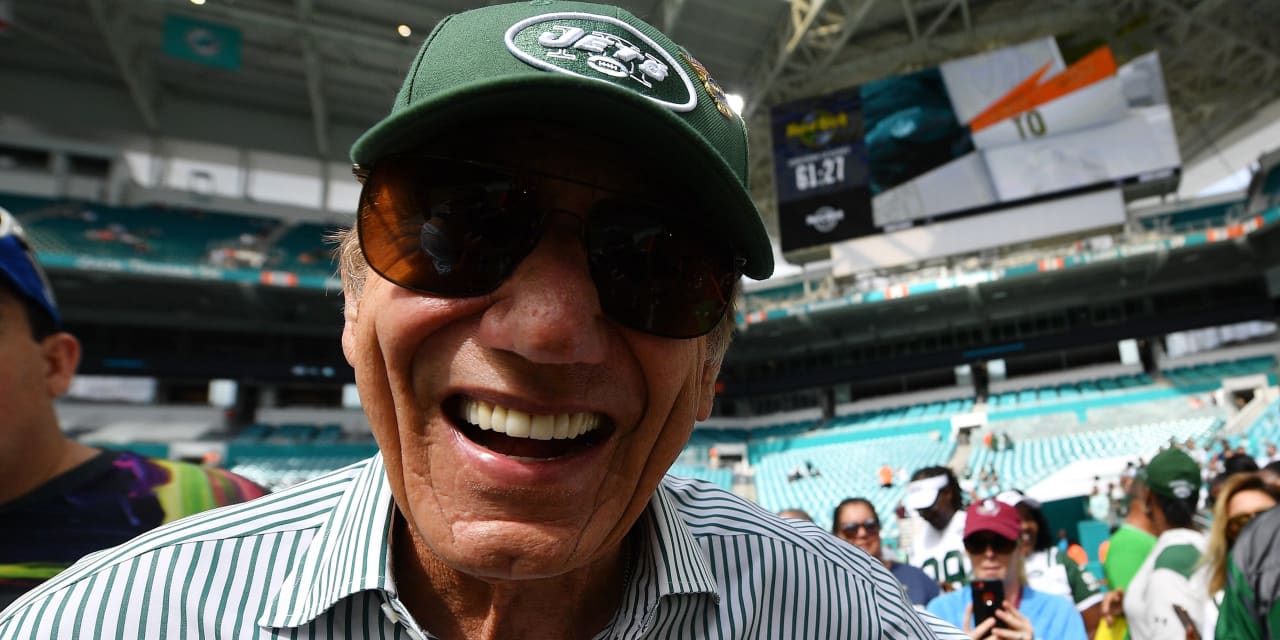

It’s the suite of Medicare plans run by private health insurance companies, and which you can sign up to as an alternative to regular or “fee for service” Medicare. You have probably seen TV commercials for Medicare Advantage plans, featuring celebrities like Joe Namath. These plans can offer things that regular or FFS Medicare doesn’t — for example by covering additional services, or by charging lower premiums (or none at all).

Medicare Advantage plans typically offer some kind of integrated managed care service, for example, with special networks of doctors and specialists, to replace the regular Medicare menu. The theory behind the program is to include choices, and private sector competition and efficiencies, in what would otherwise be a public sector, bureaucratic monopoly. You can switch from one to the other, and back again, during open enrollment every year.

Medicare Advantage is now wildly popular. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, enrollment has more than doubled in the past decade. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, the independent Congressional watchdog that oversees the program, reports that about 46% of Medicare beneficiaries now opt for Medicare Advantage instead of the regular Medicare program, and in total 186 Medicare Advantage organizations bill Uncle Sam—meaning you and me — $350 billion a year for the program. At current rates, Medicare Advantage will account for more than half of all Medicare enrollees within a year or two.

But here’s what’s got me a little perplexed.

How can this program cost taxpayers less than regular Medicare, provide seniors with more health coverage…and still find tons of extra money left over for the stockholders, the CEO, and TV advertising programs featuring celebrities?

How does that work? Are the “efficiencies” of running a managed care network really that big?

It turns out I am not alone in wondering. Congressman Frank Pallone of New Jersey has just held hearings into the so-called Medicare Advantage program, following various reports which argue that the program may not be the win-win-win that it is supposed to be.

“While there are many plans that appear to be acting responsibly,” he said during this week’s hearings, “some are not, and these bad actors are costing taxpayers money and, more importantly, jeopardizing the healthcare of seniors.”

For example, the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services recently found that some insurance companies running Medicare Advantage plans “sometimes delayed or denied Medicare Advantage beneficiaries’ access to services, even though the requests met Medicare coverage rules,” and also sometimes “also denied payments to providers for some services that met both Medicare coverage rules and MAO billing rules.”

Meanwhile there’s the staggering news that the U.S. Government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services says that it “estimates that 9.5 percent of payments to MA organizations are improper, mainly due to unsupported diagnoses submitted by MA organizations.” (My italics.)

And MedPAC told Congress in its latest report that the program does not save taxpayers money—and never has, since it was first set up in the 1980s.

“Medicare spends 4 percent more for MA (Medicare Advantage) enrollees than it would spend if those enrolled remained in FFS (here it stands for Fee For Service, meaning regular) Medicare,” MedPAC says. “The MA program has been expected to reduce Medicare spending since its inception…but private plans in the aggregate have never produced savings for Medicare.” (My italics.)

But it’s not so simple as all that. The industry argues that many of these cost comparisons are not apples-to-apples: For example, a senior with chronic health conditions is going to cost more to insure than one who is comparatively healthy. If those with worse health are more likely to sign up for Medicare Advantage, you would expect the program to be more expensive.

There are endless technical debates about how “quality” healthcare is measured, government rebates are paid out, and how beneficiaries’ healthcare needs are tracked.

Medicare Advantage plans “consistently outperform original Medicare on clinical quality measures and efficiency of care delivery,” AHIP, a health insurance industry association, told Pallone’s committee in a written statement.

The “Better Medicare Alliance,” a Medicae Advantage advocacy group, cited studies that argued the program was cheaper for taxpayers, better for beneficiaries, and highly popular with users.

Even many independent Medicare Advantage critics defend the program, arguing that it’s a good idea in theory and often in practice. The main problems, they argue, lie with complicated and flawed payment methods.

They may be right. But Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s sidekick and Svengali, is famous for talking about the way incentives drive behavior in every organization. “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome,” Munger likes to say.

My concern with all health insurance is that the insurer has an automatic economic incentive to try to give me the least amount of medical care possible. That must be true in Medicare Advantage as anywhere else. And I know that TV advertising campaigns, celebrities, and CEO pay packages don’t come cheap—and the money has to come from somewhere.