This post was originally published on this site

If you want to know why Americans are so grumpy about the economy, let’s start with the fact that despite strong job growth and sizable increases in wages, their incomes are simply not keeping up with inflation.

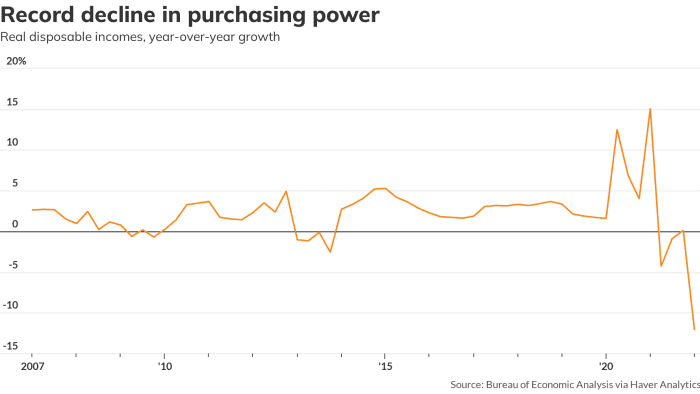

Americans just don’t feel poorer—they are poorer. In fact, they have never lost so much purchasing power in one year.

And if you think that our inflation crisis stems from “too much money chasing too few goods,” you should breathe easy now that American families are no longer getting all that money from Uncle Sam and Uncle Joe. Inflation will surely fade away now, right?

Probably not. My view is that inflation has more to do with supply issues than with excess demand. I think inflation will stay high until the supply constraints are resolved or the economy crashes.

The purchasing power of households’ incomes fell 12% in the past year

MarketWatch

Here are the data:

Real disposable incomes—how much is left after subtracting taxes and inflation—fell at a 7.8% annual rate in the first quarter of the year, the Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated Wednesday. That is virtually unheard of outside of recession.

Read more about the GDP report: U.S. first-quarter GDP shrank 1.6%. The second quarter isn’t looking much better for the economy

It gets worse. Real disposable incomes have fallen in each of the past four quarters and are down 12% in the past year, a decline that shatters the prepandemic record of -2.6% set in 1974.

Incomes have plunged by $2.5 trillion in the past year. The extraordinary drop in real incomes can be primarily explained high inflation and by the expiration of several federal tax and spending programs designed to provide relief to struggling households and businesses during the pandemic.

“ Fed Chair Jerome Powell argues that the economy is good shape and can handle higher interest rates because households are in strong financial shape with plenty of cash saved up. ”

Now, a lot of people think this drop in incomes is a good thing, because they believe that our current inflation problems were brought on by the government giving people too much money during the first two years of the pandemic in the form of higher unemployment checks, widespread stimulus checks, expanded Medicaid, the monthly child tax credit, and various other tax and spending programs.

The stimulus worked, but did it work too well?

That relief was credited with keeping millions of people out of poverty as the economy shut down and slowly reopened during the COVID pandemic in 2020 and 2021. The payments kept families fed, sheltered and clothed. But many critics say the extra cash fueled the inflationary pressures that have pushed consumer prices up by 6.3% in the past year (as measured by the same price index that the BEA uses to calculate real disposable incomes).

Our inflation is simply a matter of too many dollars chasing too few goods and services, they say.

Most of those government programs have now been dropped or scaled back. Transfer payments from the government have fallen by $2.5 trillion in the past year, with almost all of that loss hitting poor and middle-class families.

Meanwhile, taxes paid have risen by nearly $500 billion, fed by capital gains after yet another year of double-digit gains for S&P 500

SPX,

bracket creep and the expiration of the child tax credit and other temporary tax provisions. Taxes rose to 14.4% of personal income in the first quarter, just a tick off the record of 14.5% seen in 2001.

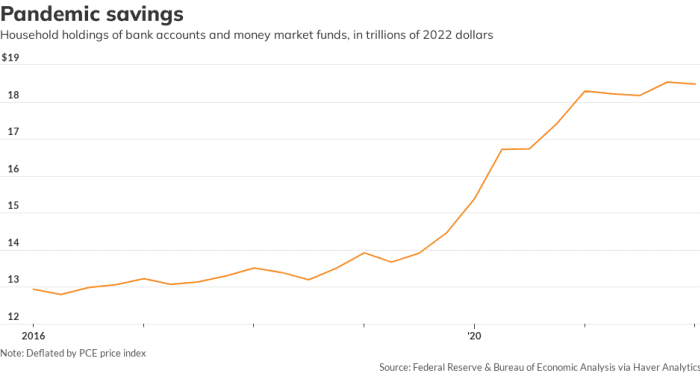

But while the government has stopped giving American families “too many dollars,” it doesn’t mean our inflation problem is licked. Because American families saved a lot of money (somewhere between $2 trillion and $4 trillion) during the pandemic, they have plenty of cash to spend, even though their incomes have fallen, some say.

The latest word from the Fed: Powell says no guarantee of soft landing for U.S. economy

Fed Chair Jerome Powell endorses this view, arguing that the economy is good shape and can handle the expected higher interest rates

FF00,

TMUBMUSD10Y,

because households are in strong financial shape with plenty of cash saved up.

Rex Nutting: Why interest rates aren’t really the right tool to control inflation

The real value of households’ checking accounts, savings accounts and money-market funds rose by about $4 trillion since the pandemic began.

MarketWatch

Theories fill the void left by the facts

Here’s where the trail of facts I’ve been following peters out: All the numbers I’ve discussed so far are aggregate data. The government adds up everyone’s savings, from Elon Musk’s to the homeless guy under the tracks and to everyone in between. What we don’t know is how that $2 trillion or $4 trillion in excess savings is distributed among the 330 million people living in this country.

If the cash hoard is mostly held by middle-class families who saved up their stimulus and child tax credit checks, then they could spend down those savings for months or even years as they try to maintain a lifestyle that their monthly income can no longer support. That would keep inflation boiling, since consumer demand would continue to exceed the supply of goods and services.

The odds of recession are rising, but the U.S. economy is not doomed to a downturn

But if the excess savings are mostly held by the ultrarich who pocketed some of their paper wealth during the great bull market of 2020 and 2021, then the inflationary pressures would be weaker. Rich people have a much lower propensity to spend out of their savings, so their cash wouldn’t fuel so much excess demand.

The Fed tries to estimate the distribution of different asset classes every quarter in its flow of funds report, but the Fed admits that its model isn’t up to the task of accurately assessing which kind of families are saving—rich or poor, young or old, black or white. The Fed is now conducting the 2022 survey of consumer finances that will pinpoint the distribution of the cash hoard, but that data won’t be released for years.

The smell test

Fed economists strongly suspect that regular families increased their savings by a lot during the pandemic. Researchers looking at anonymized bank account data from JP Morgan Chase and Bank of America come to the same conclusion.

But that doesn’t pass the smell test for me. If most families have tens of thousands of dollars in the bank or in a money-market fund, why are they so anxious about inflation? Why are they so grumpy?

My hunch is that many if not most families are struggling to pay the bills, and they are beginning to cut back on discretionary expenses as the cost of buying the necessities soars. If I’m right, consumer spending will slow faster than economists and the Fed expect. Which means the Fed may get the recession it’s hoping to avoid.

That means one of the biggest unanswered questions in the economy should be a simple one: How much do typical families have in bank? We need some answers now, Mr. Powell.

More must-reads on inflation:

The Federal Reserve can’t even get the direction of the economy right

Inflation inequality is hitting the working class harder than at any other time on record