This post was originally published on this site

Of course summer is “hot” at times for much of the U.S. But a steady tick higher in average temperatures over recent decades will push Americans to rethink how to keep summer heat tolerable, fun and above all, safe.

Humans, with our driving

RB00,

flying, cooking and more, have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the air by 40% since the late 1700s. Other heat-trapping greenhouse gases, including the methane emitted from agriculture or natural gas extraction, are also adding to pollution, though efforts to curb these emissions are underway. In all, GHGs have warmed the surface and lower atmosphere of our planet about one degree during the last 50 years, the Environmental Protection Agency says.

Closer to the ground, that means summertime has been trending hotter, including this week in much of the U.S. Since the 1980s, there have been three daily record high temperatures for every two record lows set in the U.S.

Much of the Midwest and a swath of the South felt a potentially dangerous and deadly heat this week, with temperatures that hit record highs for this time of year in some places. Combined with humidity, it easily felt like a 100 degrees or hotter in spots. More than 100 million people were expected to be affected.

Running the air conditioning overtime — if you’re lucky enough to have it — can put a strain on the electric grid and household budgets. It’s an extra expense hitting as recent consumer price index readings, which measure changes in the cost of food, housing, gasoline, utilities and other goods, rose by 8.6% over the past 12 months, a 40-year-high.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, which serves 10 million people in Tennessee and parts of six surrounding Southern states, said that on Monday, it experienced record power demand for any single day in June. It said it provided 31,311 megawatts of energy at an average temperature of 94 degrees in its region, which broke the previous June high of 31,098 megawatts that was set on June 29, 2012. The power provider said similar demand could continue through the end of the week due to more expected hot and humid weather.

Read: Yellowstone flood wake-up call: Is your home adequately insured?

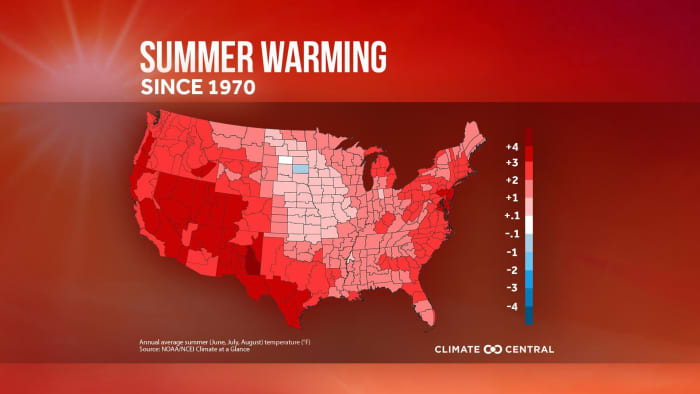

Since 1970, some 96%, or 235 of 246 U.S. locations had an increase in their summer average temperature, says Climate Matters, a nonprofit that joins scientists with science-focused communication professionals.

And 81%, or about 200, had seven or more summer days with above-normal temps. The comparison was against typical summer temperatures for a particular area spanning 1991-2020.

Nearly 40 U.S. locations had 30 or more summer days above the 1991-2020 normal. Atlanta, for instance, has had 31 days above what would already be considered toasty summer temps, since 1970.

The Southwest is getting even hotter.

Climate Central

Read: The top U.S. cities labeled as dangerous ‘heat islands’ include a few small-population surprises

Isn’t it supposed to be hot in the summer?

Yes. But it’s the frequency of heat waves, and extraordinary hot days in recent years, such as those in the typically temperate Pacific Northwest, that raise alarms.

A heat wave is defined by the National Weather Service as a period of abnormally and uncomfortably hot and unusually humid weather that typically lasts two or more days. The World Health Organization defines it in human-health terms: prolonged periods of excessive heat that results in dehydration, heat stroke, heart kidney failure and a host of heat-related illnesses that can lead to mortality.

For certain, vulnerable populations, like children, athletes, low-income households that may be without AC or great ventilation, outdoor workers, and people with chronic illnesses, are most at risk to extreme heat.

Extreme or relentless summer heat can also exacerbate poor air quality by trapping harmful pollutants close to the Earth’s surface and creating ground-level ozone. These pollutants can trigger respiratory issues in people with asthma and other lung diseases.

From 1979 to 2018, more than 11,000 Americans died from heat-related illness, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. And in a recent study, researchers concluded that heat-related deaths in the U.S. may be “substantially larger than previously reported.”

Atlanta, for instance, has had 31 days above what would already be considered toasty summer temps, since 1970.

Climate Central

Treat heat like hurricanes

The Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance (EHRA), which formed in 2020 and includes the Red Cross, mega insurers and dozens more members, has pushed for a standard practice of naming and ranking heat waves globally, just as tropical storms are.

That means communities and people can communicate about the emergency, adequately prepare and, hopefully, lives can be saved.

This month, Seville, Spain is poised to become the first city to start naming severe heat waves. Five other cities — Los Angeles; Miami; Milwaukee; Kansas City, Missouri; and Athens, Greece — have also started piloting a similar initiative, using weather data and public health criteria to categorize heat waves.

And if it gets much hotter?

By mid-century, heat waves are expected to affect more than 3.5 billion people globally — 1.6 billion people in urban centers — as they grow in frequency, duration and intensity. As temperatures rise, the urban poor will likely remain susceptible, suffering from a combination of medical conditions (e.g., cardiovascular or respiratory diseases) that are exacerbated by heat, an inadequate awareness of heat risks, and insufficient means to mitigate (e.g., costs of cooling measures such as air conditioning) the effects of high heat.

Beyond the threat to human life, economic and financial losses are substantive. According to the International Labour Organization, costs of lower labor productivity due to rising temperatures is expected to reach up to $160 billion in lost wages annually in the U.S. by 2090.

Globally, GDP losses from heat are projected at greater than 20% by century’s end.

Check out how your community handles extreme heat

The EPA maintains a Community Actions Database of measures that communities are taking to mitigate the heat island effect in their area.

Emergency management can help reduce climate risk in vulnerable communities. FEMA has a dedicated page with tools, data, and resources on climate resilience.

And, for state-specific emergency management information, search for your state on the USA.gov site.

Read: Was the deadly Kentucky tornado due to climate change? It’s ‘complicated.’

The Associated Press contributed.