Last week, crypto investors learned just how dangerous stablecoins can be. TerraUSD (UST)

USTUSD,

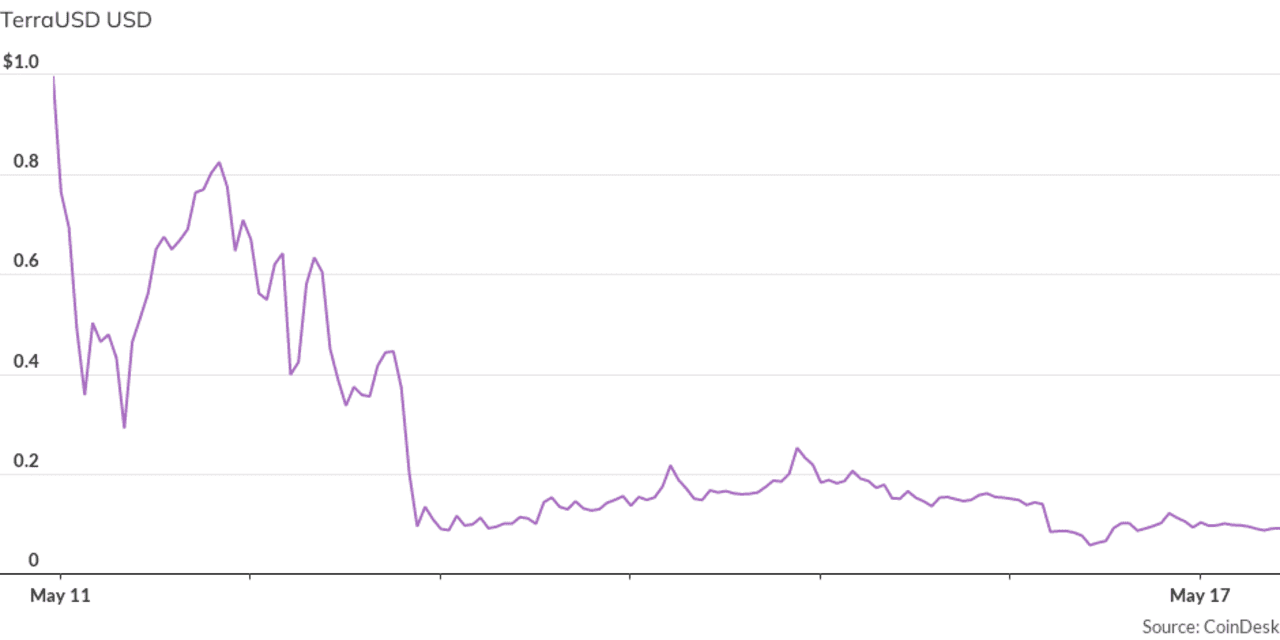

—until recently the third-largest stablecoin by market capitalization—plunged more than 87% in value to $0.12 as of Monday afternoon, causing more than $16 billion in losses to UST holders and sending ripple effects across the crypto market.

Observers and scholars have long warned of the unique risks posed by stablecoins—while promising that they can always be exchanged one-to-one for actual U.S. dollars

BUXX,

stablecoins can run.

Longstanding authority

The fact that UST “lost its peg” caused many commentators to call for new legislation to govern stablecoins. These calls, however, ignore the reality that federal agencies hold longstanding statutory authorities to impose stability on these products, which they should use immediately.

Although stablecoins appear novel, UST’s failure is not a new phenomenon.

Bank runs were a frequent occurrence before the Great Depression (think “It’s a Wonderful Life“), and money-market mutual funds, a class of investment products developed in the 1970s in which shares aim to be pegged to $1, can also run.

Yet Congress and financial regulators have acted to defend banks and money-market funds against runs: In 1933, Congress effectively prohibited entities from accepting demand deposits (that is, taking dollars with the promise of on-request redemption) unless they chartered banks or were regulated like banks, and the Securities and Exchange Commission highly regulates money-market funds to ensure their stability, and may soon subject them to even tighter scrutiny.

Two options for regulation

The collapse of UST indicates that action must be taken right away, as the failure of a stablecoin can be a significant market event that poses risks to markets and harms asset holders who expected their tokens to maintain their value. Fortunately, the existing financial regulatory laws can and should be used to tackle the problem now.

Given their structure and operations, if stablecoin issuers want to operate in the United States and issue tokens pegged to $1, they have two choices: 1) They can either obtain a bank charter and be regulated as a depository institution subject to state or federal banking laws and deposit insurance requirements, or 2) they can register as a money-market fund and be regulated as such.

If a stablecoin issuer does not become a bank or a money-market fund, federal authorities have two options for enforcing the law.

The first option is Section 21(a) of the Glass-Steagall Act, which makes it unlawful to take deposits repayable on demand unless the person receiving the deposits is regulated like a bank. Since violation of this law is a criminal offense, the U.S. Justice Department could bring enforcement actions against stablecoin issuers for unlawfully accepting deposits because the issuers are not banks.

In effect, this would mean that only regulated banks would be able to issue stablecoins—which would likely lead to less volatility than under today’s status quo of minimal oversight.

Alternatively, the SEC could use the Investment Company Act of 1940 and Rule 2a-7. The act requires any entity that is “being engaged primarily…in the business of investing, reinvesting, or trading in securities” to register with the SEC. Rule 2a-7 requires money-market fund issuers to adhere to strict standards regarding the makeup of their assets and operations to prevent runs from occurring.

In effect, each stablecoin would be an ownership share of the pool of assets, and the SEC would regulate the assets the issuer could purchase.

Unregulated and risky

The collapse of UST demonstrates that stablecoins pose significant risks to crypto investors so long as they continue as unregulated, risky investment products. While Congress has begun considering legislative options to regulate stablecoins, regulators already have the authority to take urgently needed steps and should not wait for Congress to act.

The law already makes clear that stablecoin issuers must either be regulated as banks or as money-market funds. Either of these two options would allow federal authorities to immediately act using longstanding laws designed to mitigate this exact kind of market turmoil—and either option is preferable to today’s lightly regulated environment.

Importantly, SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has recognized that stablecoins fall within his agency’s jurisdiction and has committed to ensuring stablecoin issuers comply with the securities laws. Gensler should work with the DOJ to make use of their existing authorities to protect investors and bring clarity to the regulatory environment around stablecoins.

Todd Phillips is the director of financial regulation and corporate governance at the Center for American Progress. Alex Fredman is a research assistant at the Center.

More on crypto regulation

Terra crash sharpens Washington’s attention on crypto regulations

Yellen says run on UST stablecoin illustrates crypto’s risk to financial stability

From Barron’s: Senate Bill Would Give Washington Huge Powers Over Crypto