This post was originally published on this site

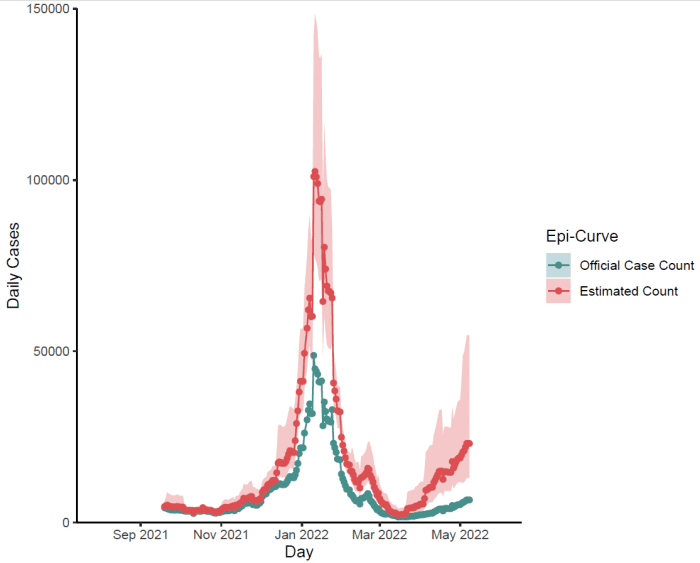

The majority of people in the U.S. who are testing positive for the coronavirus right now likely aren’t being included in official case counts, and that means our understanding of current — or future — waves of the virus is weaker than it’s been in the past.

For the week ending May 7, there were an estimated two positive COVID-19 laboratory tests for every five positive at-home tests, which largely go unreported.

The crowdsourced data comes from Outbreaks Near Me, a site that gathers voluntary information from individuals to identify COVID-19 hot spots through a partnership with Momentive

MNTV,

the company that owns SurveyMonkey.

“A couple of weeks ago, we had a shift, where more people are now testing positive with the at-home tests than all other testing combined,” said Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist and chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital. (Outbreaks Near Me is a project that came out of his laboratory at the hospital.)

The widespread availability of at-home tests has been a good thing for Americans. Ever since the start of this year, when the Biden administration made at-home COVID-19 tests available free to American households, they’ve become part of our everyday lives. Boxes of BinaxNow and FlowFlex are stacked near pharmacy checkout lines. A certain number of tests can be reimbursed by insurance. And fewer people are waiting in long lines for a PCR test or days to get a result.

But there’s downsides to these tests. Because there is no easy way to report results to local or state governments, this data isn’t often included in official case tallies, which are used to calculate positivity rates and can serve as an indicator of the amount of virus in a community.

“The more that people start to use these tests, the more that it will create this further gap between what public health knows and is able to respond to and what’s actually happening on the ground,” Brownstein said.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in New England is rising, though many of those infections are not being included on official case counts because they were detected using at-home tests. Source: OutbreaksNearMe and Momentive

A new wave?

The number of new infections in the U.S. has doubled over the past month due to the spread of BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 — both subvariants of omicron. The U.S. reported about 161,000 new cases on Wednesday, the largest number of new daily infections over the past three months and largely driven by an increase in cases in the Northeast, according to the New York Times case tracker.

“We’re probably in the midst of a large surge,” said Dr. Michael Mina, a former Harvard University epidemiologist who is now the chief science officer at eMed, which connects at-home tests with telehealth services. “We’re seeing right now rates that are higher than any other time in the pandemic, with the exception of during the very, very, very peak of omicron.”

The U.S. first saw a signal in wastewater surveillance that COVID-19 cases were rising around mid-March. Then the number of new infections begin to climb around mid-to-late March. Hospitalizations, which tend to lag cases, recently began ticking up and have increased 20% over the last two weeks, according to the Times tracker. Death rates, which usually tail hospitalizations by a few weeks, are still low, with about 320 new deaths being reported every day.

Mina, who has long been a proponent of at-home testing during the pandemic, now sees two problems with at-home tests.

Not only are the results not often included in official case counts, people who do find out they have tested positive for the virus are sometimes unclear what to do next. They may wait to seek care until it’s time to be hospitalized or miss the window to be prescribed the antiviral Paxlovid, which should be started within five days of symptoms.

“People just aren’t acting upon their self test, and they’re also not reporting so it’s kind of a double whammy,” he said.

Other changes to how the U.S. tests for COVID-19

The increasing use of at-home tests is one reason why official case counts may not reflect a more accurate tally of new infections, but there are several other factors that are influencing the perception of COVID-19 prevalence right now.

-

The government in March stopped paying for tests for uninsured Americans, a decision that prompted Quest Diagnostics Inc.

DGX,

+0.22%

to begin asking for payment upfront from those individuals. (“As a result, we’ve seen a decline in our uninsured COVID-19 molecular testing volumes in late March and into April,” the CEO recently said.)

- Most states this spring changed how often they report COVID-19 information, according to a Nature editorial published in March. Washington, D.C., hasn’t reported infection data to the CDC for two weeks, according to the Washington Post, and Florida now reports COVID-19 data every two weeks.

- And, finally, there’s pandemic fatigue. Experts say some people are no longer worried about testing as local and state governments have lifted mask mandates and milder infections among the vaccinated and boosted have been reported.

So, why does it matter?

Public-health experts say that there is an additional concern to consider: the U.S. uses samples gathered from PCR tests to conduct genomic surveillance of the virus. This is how we identify new variants.

“We’ll have gaps in our ability to see a new variant emerge here,” Brownstein said.