This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

You know that feeling when you’re having a delightful time at a picnic, but you start seeing storm clouds in the horizon? That’s pretty much what prospects for retirement look like for most working Americans, according to the latest annual survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) and Greenwald Research.

Data in the Retirement Confidence Survey suggested two major storm clouds: 1) expectations that the Federal Reserve may raise interest rates repeatedly in 2022, leading to costlier credit cards and loans as well as rising debt loads and 2) a continuation of steep inflation (currently at an annual rate of 8.5%), putting the squeeze on savings and household budgets.

For low-income workers with little savings today, however, those storms are already here. And their chances for a comfortable retirement seem likely to worsen in the year ahead due to those lurking negative economic forces for 2022.

Retirement confidence in the U.S.: The big split

EBRI’s survey — a January 2022 online poll of 1,545 workers and 1,132 retirees — said that 42% of workers with incomes under $35,000 feel less confident about retirement as a result of the pandemic and its economic impact.

“They’re feeling that nothing is helping them” for retirement, said Craig Copeland, director of Wealth Benefits Research at EBRI, a nonpartisan, nonprofit research institute based in Washington, D.C., and chief researcher for the group’s 32nd annual Retirement Confidence Survey. “The pandemic has really split the economic workforce between those that have well-paying jobs and those that don’t.”

The EBRI survey results echo recent ones about the pandemic and Americans’ finances from the Pew Research Center. According to Pew, a nonpartisan think tank also based in Washington, D.C., “the financial hardships caused by the COVID-19 recession in the U.S. were endured mostly by lower- and middle-income families.”

More from the survey: A majority of workers have confidence in Social Security. Should you?

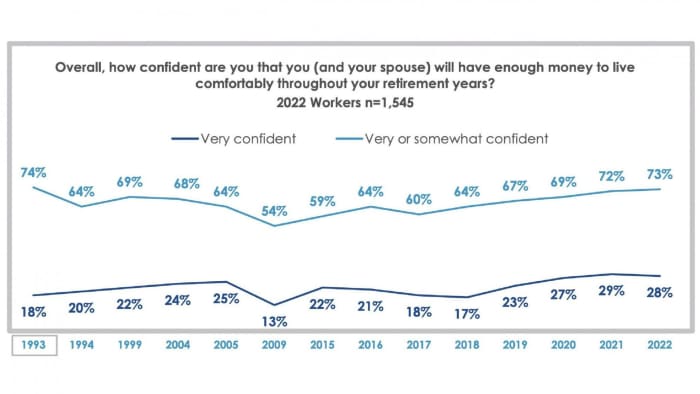

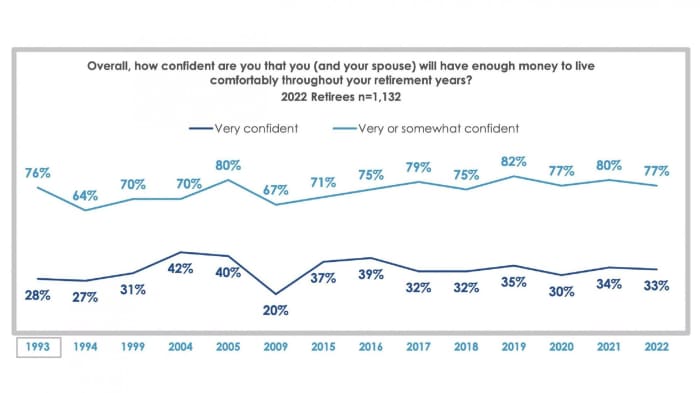

Overall, retirement confidence remained about where it was a year ago for both U.S. workers and retirees — pretty high. And the numbers are significantly higher than in EBRI’s survey soon after the pandemic began in March 2020.

Some 73% of workers and 77% of retirees now say they are very or somewhat confident they (and their spouses, if they have them) will have enough money to live comfortably throughout their retirement years. And roughly a third of each group are very confident about their retirement outlook.

By contrast, in 2009, just 54% of workers and 67% of retirees were confident about retirement. Back then, only 13% of workers and 20% of retirees were very confident.

The workers least confident about retirement: members of Generation X, who are now aged 42 to 57 and closing in on the traditional age of retirement. “They don’t know where they’ll be come 65,” said Copeland.

How debt loads affect retirement outlooks

More than half of workers surveyed and one in three retirees said their debt level is a “major or minor problem.” And those with major debt problems were especially fearful about retirement.

2022 Retirement Confidence Survey/Employee Benefit Research Institute

Nearly half of workers said debt has hurt their ability to save for retirement and EBRI saw a rise in the percentage of retirees saying debt has made it harder for them to live comfortably in retirement.

“Debt affects people’s ability to save, their ability to participate in retirement plans and to save for emergencies.”

Some 54% of workers who said they had major debt problems felt less confident about retirement due to the pandemic, compared with just 19% of those with no debt problem. Similarly, 61% of retirees with major debt problems felt less confident about retirement, compared with 15% of retirees with no debt problem.

Also see: Can we close the retirement security gaps in America?

“Debt affects people’s ability to save, their ability to participate in retirement plans and to save for emergencies,” said Copeland. “So, it ends up just being a snowball effect if they don’t get control of debt.”

Participating in a 401(k) retirement savings plan at work is also a key factor in Americans’ retirement confidence. EBRI found that 42% without such a plan felt less confident about retirement due to the pandemic.

2022 Retirement Confidence Survey/Employee Benefit Research Institute

Only about two-thirds of private-industry workers in the U.S. have employer-sponsored retirement plans, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Nevin Adams, head of research at the American Retirement Association, a nonprofit that represents five retirement industry associations told the New York Times that workers are 12 to 15 times more likely to save for retirement if they have a retirement plan at work.

What about inflation?

The effects of rising inflation on retirement began showing up a bit in this year’s survey. But since the study was conducted before the past few months’ consistently high Consumer Price Index figures, inflation was not yet a concern to most respondents.

Roughly two-third of workers and 72% of retirees were confident they would have enough money to keep up with inflation in retirement, though 35% of workers who felt less confident about their ability to live comfortably throughout retirement cited inflation as the reason.

Retirees who told EBRI they were spending more than they had anticipated cited a combination of the rising cost of housing and treating themselves to more traveling and entertainment than they expected.

Copeland said he thinks that if inflation persists — which looks likely for 2022 at least — that will depress retirement confidence. In early April 2022, 72 economists surveyed by Bloomberg said they expect inflation to average 5.7% in the final three months of the year; a month earlier, they forecast 4.5%.

How and when people plan to retire

Some of the EBRI survey’s findings about what people expect to do in retirement and when they expect to retire (if at all) were especially fascinating.

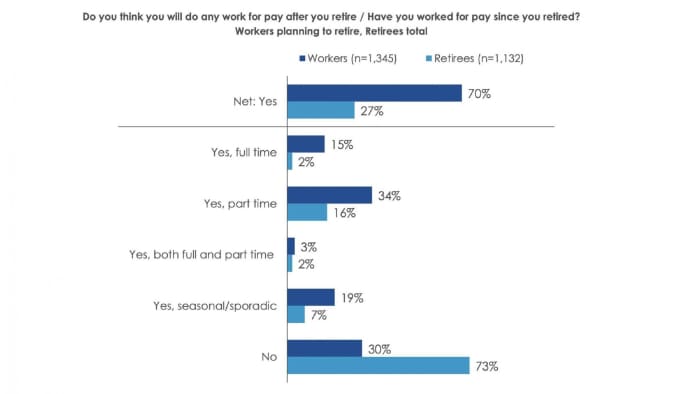

As in the past dozen years or so, the new survey revealed a wide chasm between the high percentage of workers who said they expect to work part-time in retirement and the low percentage of retirees who actually are working.

While 68% of workers told researchers that they expect work for pay will be either a major or minor source of their retirement income, only 20% of retirees have employment income.

2022 Retirement Confidence Survey/Employee Benefit Research Institute

Copeland cited a few explanations for the disparity. Some people who think they will work in retirement don’t because of health issues, an inability to find jobs or a lack of interest in employment. Nearly half of retirees EBRI surveyed said they retired earlier than expected.

The Great Resignation is playing a role, too, in the realities of working in retirement, Copeland noted. He said some new retirees have quit their jobs because they felt unfilled there and haven’t discovered part-time positions that get their juices flowing.

This, Copeland added, also partly explains why only 44% of workers said they expect to gradually transition to retirement, down from 51% a year ago.

While a third of workers expect to retire between ages 62 and 65, a growing percentage now expect to quit full-time work between ages 66 and 69 — 14%, compared with 11% in 2021. And a shrinking percentage plan to retire between 55 and 59 (7%, down from 11% last year).

Copeland attributes this partly to the inching up of Social Security’s Full Retirement Age for benefits. It was age 65 for people born in 1937 or earlier (they’re now 85 or older) and has crept up to 67 for those born in 1960 or later (who are now 62 or younger).

Don’t miss: How to invest now as your 401(k) tanks — according to a top money manager

Social Security benefits rise 8% for every year recipients delay claiming between their Full Retirement Age, as determined by the Social Security Administration, and age 70. “People are starting to understand that if they can work an additional year [past their nominal Full Retirement Age], that’s a big return on their Social Security,” said Copeland.

Growing concern about Social Security and Medicare

Speaking of Social Security, EBRI’s study found that workers are growing gloomy about the future of both Social Security and Medicare and what that might mean for their retirement.

Just 14% of workers said they were very confident the Social Security system will continue to provide benefits of at least equal value to the ones retirees receive today. A year ago, 17% said this.

Just 15% of workers are very confident the Medicare system will continue providing benefits of at least equal value to those retirees now receive, down from 18% in 2021.

Also on MarketWatch: What dogs can teach us about life and death

This makes sense, considering that Social Security’s trustees said in September 2021 that Social Security would be insolvent by 2033, a year earlier than what they said in 2020. And Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which pays for Medicare Part A medical services, is now expected to be able to pay scheduled benefits only until 2026.

“Funding continues to be a challenge for both,” Copeland said.

Which means, unless Congress and the president get serious about dealing with these two solvency problems, retirement could be an increasing challenge, too.

Richard Eisenberg is the former Senior Web Editor of the Money & Security and Work & Purpose channels of Next Avenue and former Managing Editor for the site. He is the author of How to Avoid a Mid-Life Financial Crisis and has been a personal finance editor at Money, Yahoo, Good Housekeeping, and CBS Moneywatch.

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2022 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: