This post was originally published on this site

When interest rates rise, as is happening now at an accelerated pace, bond prices fall. But that doesn’t mean you should avoid bonds.

You may have read that bonds have performed poorly as the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy. That’s only half the story. Credit quality in the U.S. is strong — defaults are rare. Nearly all bond issuers are making interest payments on time.

Holding a portion of your portfolio in bonds is actually a way to cut risk. That may sound counterintuitive but read on. Explained below are strategies that can help you mitigate the risk of bond investments, even though the current interest-rate cycle will likely push prices down.

The mechanics of bonds

Bonds’ market values have declined. What does that mean to you? If you hold a bond and plan to keep holding it until it matures, the decline in market value doesn’t change the fact that you will receive the face value when it matures.

If you purchased a bond at a discount (for less than the face value), you will have a gain when it matures. Vice-versa if you paid a premium for your bond. The day-to-day price fluctuation doesn’t affect the payout at maturity. You continue to receive interest until the bond matures.

But if you own shares of a bond fund, your share price has been declining. But the interest is still flowing, and as bonds mature in the fund, they will be redeemed at face value and replaced with higher-paying (or higher-yielding) bonds. That eventually helps the share price to recover. How much does the decline in your bond fund’s share price bother you?

With inflation running at a 40-year high, it may take a long time before the upward direction of interest rates (and consequent decline in bonds’ market values) reverses. Can you wait? How long might you have to wait?

If you have money to invest, bond-fund or individual bond investments have already become more attractive with higher yields.

A case for bonds

A traditional model for stock- and bond-market exposure is called 60/40, with 40% of a portfolio invested in the bond market either though individual holdings or shares of bond funds.

The notion of a 60/40 portfolio seemed antiquated during the long period of declining interest rates, when stocks have produced some of the best performance in decades.

Central banks’ stimulus, low interest rates and very low (or even negative) yields for long-term bonds have pushed money into U.S. equities. The S&P 500 Index’s

SPX,

average annual return (with dividends reinvested) for the past five years is 15.8%. That compares to an average of only 7.3% for the previous 10-year period, according to FactSet.

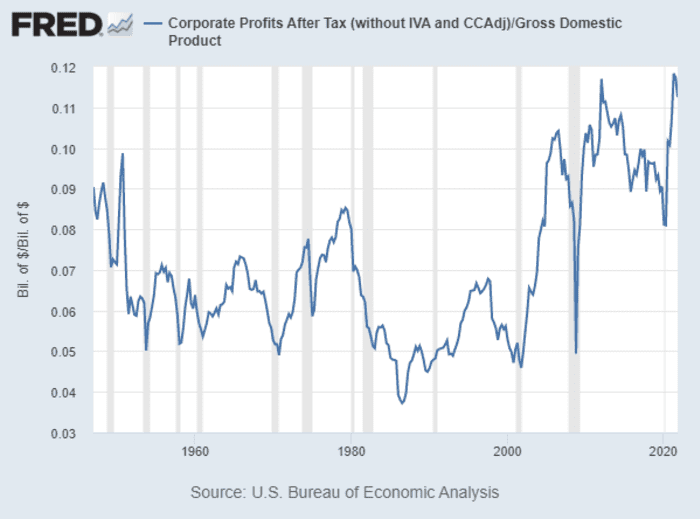

Meanwhile, profits for U.S. companies hit their post-war maximum during 2021:

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

High inflation and rising costs, especially for labor, and an eventual resistance to price increases, may push the the above chart in the other direction. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve is pointing to an accelerating cycle of increases for short-term interest rates and a reduction of its bond holdings, which has the bond market already sending long-term rates significantly higher this year.

Taken together, that makes this an ideal time to consider adding more bond-market exposure, according to Mark Hulbert.

Find out your bond fund’s duration

A bond portfolio’s average duration is a measure of its sensitivity to the movement of interest rates. It factors in premiums or discounts when bonds are purchased and is expressed as a number of years. The higher the duration, the more volatile the bond fund will be as interest rates move up or down, and the longer it will take for a downward price cycle to reverse as bonds mature at face value and are replaced by higher-yielding bonds.

Hulbert explains how duration affects volatility and provides simple advice on how to reduce bond-fund risk in this aptly named article, as part of the How to Invest series:

A bond fund’s name will give you some idea of its duration — the fund may have “intermediate” or “short-term” in its name. But you should find out your fund’s exact duration, which is easy to do on the fund manager’s website. The average duration for the Vanguard Intermediate Term Treasury ETF

VGIT,

for example, is 5.4 years.

Since most bond funds are managed to maintain their average duration, Hulbert cited research showing that a good rule of thumb is that if you hold a bond fund in a rising-rate environment and your share price falls, the replacement of maturing bonds with higher-paying bonds will make up for that decline if you hold on to your investment for a period of at least one year less than twice the fund’s average duration.

So for Vanguard’s VGIT, that would mean being able to stay in for almost 10 more years. Would you be able to do that without worrying through the worst period for price declines? If so, a bond fund with a similar duration remains a viable way to diversify your portfolio away from stocks.

The case for owning bonds until maturity

If you buy your own bonds and hold them until maturity, you know how much you will be paid back when the bonds mature. You might have an easier time navigating a period of declining bond prices than you would if you were watching your bond-fund share price decline.

Ken Roberts, a registered investment adviser with Four Star Wealth Management based in Truckee, Calif., helps income-seeking clients with strategies in the bond and stock markets. He discussed various income strategies during an interview.

First, here’s a list of yields at the end of the day on April 6 for U.S. Treasury securities of various terms:

Click on the maturities in the left column to go directly to that Treasury security’s quote page.

Click here for Tomi Kilgore’s detailed guide to the wealth of information available for free on the MarketWatch quote page.

The above shows the yield curve for U.S. Treasury securities. Interest paid on Treasury bills, notes and bonds is exempt from state and local taxes. Depending on your tax situation, you might prefer to invest in municipal bonds, which are exempt from federal income taxes.

The Treasury table provides a good indication of the overall bond-market rate curve, and you can see that three-year and five-year notes have higher yields than 10-year notes. This has been an indicator of previous recessions, however, it might have a very long lead time.

Roberts outlined three typical strategies for bond portfolios:

-

Bullets. This strategy means loading up on intermediate-term bonds. Three-year U.S. Treasury notes

TMUBMUSD03Y,

2.733%

have a higher yield than 10-year Treasury Bonds

TMUBMUSD10Y,

2.703%

and even 30-year bonds

TMUBMUSD30Y,

2.722% . - Barbells. This means allocating to the short and long sides of the yield curve. The advantage on the short side is quick maturities that might be replaced with higher-yielding paper as rates rise. This strategy “probably isn’t best” for the current rate environment, according to Roberts, because of the inverted yield curve. “The bullets make more sense,” he said.

- Ladders. This is a strategy followed by many bond funds. It “probably works best when the yield curve is normal,” Roberts said. A normal yield curve is one in which longer maturities have progressively higher yields. He provided this example: If you have $200,000 to invest in bonds and want to do a 20-year ladder, you cant allocate $10,000 for a bond that matures a year from now, and so on, out to 20 years. “Then you have one maturing every year. So if rates rise, you go out further and lock in rates. If rates fall, you lock in gains. It is a good strategy to work with, for different interest rates,” Roberts said.

These strategies may seem complicated, but they are typical ones that you can follow with the assistance of a broker of investment advisor.

Other Treasury bond strategies

TIPS

TIPS stands for Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, which pay interest twice a year and have their principal amounts adjusted upward, based on the inflation rate, or downward if there is deflation. The interest rate is applied to the adjusted principal, so these securities offer good protection for investors in a high-inflation environment.

Roberts pointed out that investors can participate in TIPS in an easier way, with an exchange traded fund, such as the iShares TIPS Bond ETF

TIP,

The ETF pays a monthly dividend.

A more sophisticated strategy for the TIP ETF is to make use of covered-call options to increase income. You can read about covered-call income strategies in detail here.

I-Bonds

Series I savings bonds are available directly from the Treasury. It is easy to set up an online Treasury Direct account. Savings bonds might seem to be a quaint notion until you realize that I-Bonds are now yielding 7.12% if you purchase them before the end of April. The rate is adjusted every six months, in May and November, based on the U.S. inflation rate. Interest is added to the bonds and paid when you redeem them.

I-bonds must be held for at least a year. They can be redeemed after five years with no penalty. If you redeem earlier, the penalty is three months’ interest. Keeping in mind that this is money you wish to invest for the long term outside the stock market, that penalty isn’t very high, especially when inflation and the I bonds’ interest rates are so high.

Treasury Direct accounts are set up as individual or corporate accounts. The regular limit for annual purchases of I-Bonds is $10,000. However, you can also receive I-Bonds in place of your federal tax refund, up to $5,000 a year. For a couple, two individual accounts make for a regular annual limit of $20,000.

Hulbert digs further into I-Bonds and their tax implications here.

Don’t miss: These 10 dividend stocks with yields of at least 5% can help you take on stagflation or a recession