This post was originally published on this site

A major advocate for investors who want companies to reveal how they’re contributing to, or trying to limit, climate change has been updated to reveal some 69% of the companies targeted have now made net-zero emissions commitments for the coming decades.

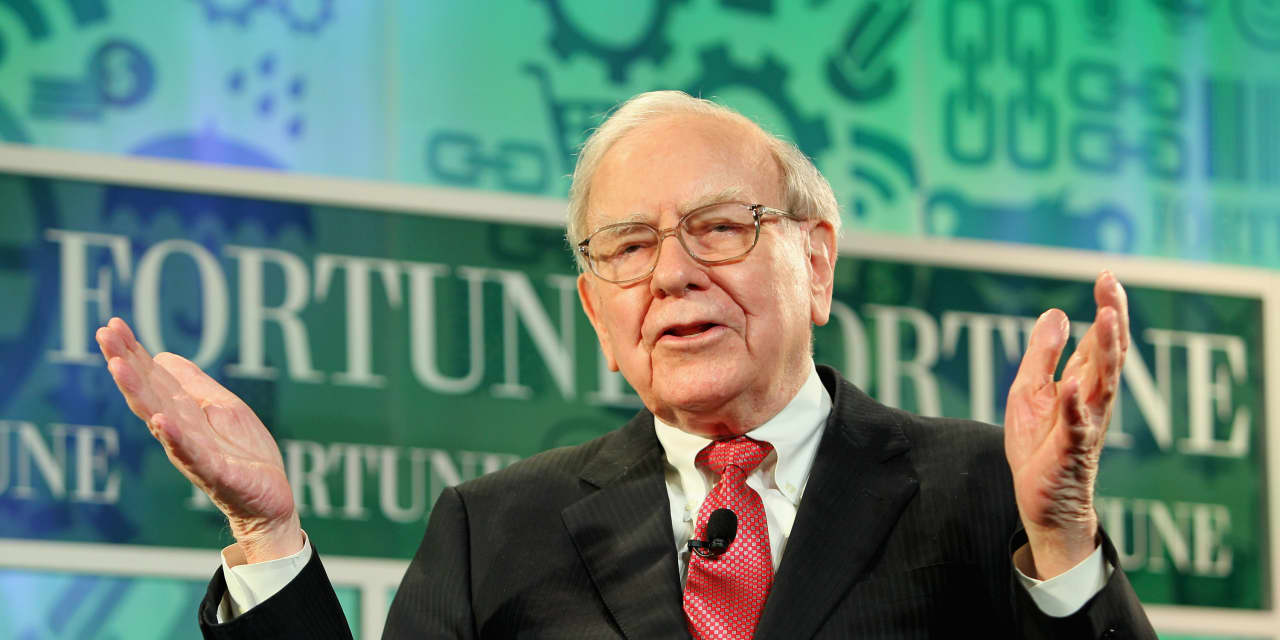

But that updated global list, called the Climate Action 100+, reveals one notable North American holdout: Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway

BRK.B,

The holding behemoth that dips into dozens of sectors has historically been betting both on the resilience of traditional fossil-fuel industries for the foreseeable future and on newer energy sources. Buffett, for instance, has backed efforts to build the U.S.’s largest solar installation.

Last year, in his always highly anticipated shareholder letter, Buffett said: “We’ve invested in excess of $30 billion into renewables, and have really completely changed the way our businesses do business, i.e. our utility businesses. They have been decarbonizing and delivering a valued product to our stakeholders, to our customers.”

But there are corporate practices that get Buffett and Berkshire compared to the opaque reporting of PetroChina

PTR,

the listed arm of China’s state-owned energy interests: no access to emissions data or other parts of the climate-change ledger, at least in any official capacity.

““I think that the message that investors are trying to give to companies is to say, ‘Hey, if you’re not at least disclosing or following TCFD disclosure, you’re going to be behind the curve even in terms of regulation.’””

With the Climate Action 100+ results, it’s clearer that some companies are trying to get ahead of expected tougher regulation in reporting environmental risk, including a company’s own energy-usage track record, its emissions from main operations, and how much pollution its suppliers and customers might be spewing into the atmosphere, which are known as Scope 3 emissions and are the most difficult to report. The Securities and Exchange Commission earlier this month advanced its proposed climate-change reporting rules for stock-issuing companies.

“I think that the message that investors are trying to give to companies is to say, ‘Hey, if you’re not at least disclosing or following TCFD disclosure, you’re going to be behind the curve even in terms of regulation,’” Morgan LaManna, director for investor engagements at Ceres, the nonprofit that created the Climate Action program, told MarketWatch. TCFD, or the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, was created in 2015 to develop apples-to-apples, voluntary climate-related financial-risk disclosures for use by companies, banks and investors in providing information to stakeholders.

“That’s a big focus with Berkshire Hathaway, which is one of — actually it’s the only — North American company that meets none of the disclosure criteria on the [Climate Action 100+] benchmark, both last year and this year,” said LaManna.

“So I think companies like that, I mean, they’re going to be way behind when it becomes regulation,” she said. “And it is also an opportunity for these companies, you know, to be leaders.”

‘More challenging net zero by 2050 scenario’

The benchmark for corporate climate reporting established in 2021 for the Climate Action 100+ program has just undergone a second round of assessments, essentially measuring progress against the reporting yardstick set last year, and it will be due for an annual review moving forward. With the update, the companies on the list are assessed against the International Energy Agency’s more challenging “net zero by 2050 scenario” when applicable. It also added new indicators and assessments focused on a “just transition” as well as climate accounting and auditing.

Search by company or read the full list.

The Climate Action 100+ has been billed as the world’s largest investor engagement initiative and aims to get more big economic engines and notable polluters to make emissions pledges — or at least expose their progress to investors. Backing the program are 700-plus investors, including fund managers, pension funds and others, with a combined $68 trillion in assets.

“The global focus list of companies spans some 30 different countries. They’re really important to the economies in each country. And they’re the world’s biggest greenhouse-gas emitters. There are 54 companies to make the list based in North America,” said LaManna.

Buffett’s reluctance is also magnified considering the traditional energy, agricultural and auto maker names called out positively in the Ceres update. For instance, nine companies have newly set medium-term Scope 3 (indirect emissions) targets since last year: Bunge

BG,

Chevron

CVX,

Ford

F,

General Motors

GM,

Paccar

PCAR,

Phillips 66

PSX,

Procter & Gamble

PG,

Wayerhaeuser

WY,

and Xcel

XEL,

The focus companies assessed have an imperative to act, as they are responsible for 80% of global industrial greenhouse-gas emissions, Ceres said.

Proxy season looms

The assessments also come as the Ukraine invasion has reinvigorated calls in Washington for a clean-energy transition and prompted those largely representing fossil-fuel

CL00,

states to double down on calls for U.S. energy independence based on traditional drilling and pipelines. Its release is timely too, as it will help inform shareholder voting heading into the 2022 U.S. proxy season, which is expected to feature the most climate-focused attention to date.

The update shows some progress from companies toward the goals set with the 2015 U.N. Paris agreement. That effort says global warming ideally does not exceed 1.5 degrees C, and at the least is capped below 2 degrees. According to the report:

- 69% of companies worldwide now have net-zero emissions commitments, including 33 companies in North America.

- Roughly three-quarters of North American companies have set medium-term emissions-reduction targets, including the nine companies noted above that set medium-term Scope 3 (or indirect emissions) targets since the last round of assessments.

- 90% of companies have some level of board oversight of climate change, and 89% are now committed to or have already produced a TCFD report.

Improvement isn’t meant to invite complacency, Ceres stressed.

Much more corporate climate progress is needed to stave off the worst impacts of the crisis, which is worsening, as the latest report from the U.N. made clearer than ever.