This post was originally published on this site

Child care is one of the most significant expenses for American families. Costs top housing and often college tuition. While child care is often presented as a personal, family issue, parents’ abilities to find and afford child care is inextricably connected to economic stability and growth, and the strength of the nation’s economic recovery relies on bold child-care reform.

In the State of the Union address earlier this month, President Joe Biden shared that many families pay up to $14,000 per year on child care, but that number does not capture the full cost to parents and communities.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has broken down the costs of lack of child care into three major buckets: lost income for individuals, primarily mothers, who miss work or leave the workforce, the cost to businesses of replacing employees who are forced out of work due to care challenges, and lost tax revenue to states and the federal government.

$57 billion

The cost of an unstable child-care sector on the country’s economy is immense.

The national economy loses upward of $57 billion annually, directly attributable to child-care issues. And these issues are largely shouldered by women—particularly women of color—whose families often depend on their earnings.

During the pandemic, millions of women left their jobs and nearly 1.2 million fewer women are in the workforce today relative to pre-pandemic levels. According to Wells Fargo economists, nearly one million additional women would enter the workforce if mothers of children under age 6 were able to work at the same rates as mothers of school-age children.

Women’s abilities to participate in the workforce are critical for their families’ economic security as well as broader economic growth.

Costs skyrocketing

Federal guidelines recommend that parents pay no more than 7% of their income for child care. Yet, even before the pandemic, families who paid for child care spent, on average, 10% of their income on child care—and low-income families spent nearly 35%. The impacts of such high costs are significant for parents, particularly for women who face a long history of wage discrimination.

Since the pandemic, these costs have skyrocketed, and child-care prices have soared at double the rate of inflation.

For families with infants, the need for relief is even more dire. At the start of the pandemic, in most states, there were child-care slots for fewer than one-quarter of children under age 3. Infant and toddler care also tends to be more costly than care for older children (sometimes 50% more). Reductions in parents’ incomes, most often mothers, following the birth of a child result in additional debt, which in addition to increasing costs of care, compounds financial stress for families at a vulnerable time.

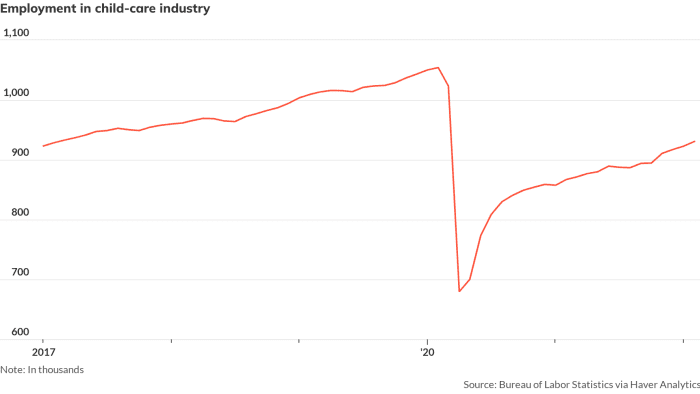

The number of jobs in the child-care industry is down more than 10%.

MarketWatch

Poverty wages

While cutting staff wages is typically a first choice for providers looking to reduce expenses, they end up contributing to significant financial struggles for workers, who are overwhelmingly women, and disproportionately women of color—deepening existing inequities. The child-care workforce is paid poverty wages.

As anyone who has ever spent time with a toddler knows, child care is difficult work, yet the average hourly wage for a child-care worker is $11.83. Even child-care professionals with master’s degrees struggle to afford basic needs, sometimes skipping meals, and nearly one-quarter take on other jobs. More than half rely on some form of public assistance.

As of February 2022, the child-care sector employment remained 11.7% below its February 2020 level—in stark contrast to the overall workforce recovery. This workforce-specific recovery also differs from women’s overall jobs recovery, which has now reached 98% of its pre-pandemic levels.

Top economists at Wells Fargo estimated that nearly half a million families still struggle to find care, accounting for more than half of the remaining drop in the labor force since the pandemic began. Given the disproportionate expectations of care placed on mothers, many—particularly moms of color—are left without choices. Parents, especially moms, are forced to leave the workforce to, impacting their long-term professional advancement and earning potential, while also making it more difficult for employers to hire. Conversely, other women, whose families depend on their incomes, are often forced into choosing expensive care arrangements, far from their homes in order to keep working and make ends meet.

The American Rescue Plan, which just celebrated its first anniversary, provided critical rescue dollars that helped states stabilize their child-care sectors and extend support to marginalized communities. But rescue plans are not permanent plans.

Dangerous spiral

Without a permanent solution, the child-care market is entering a dangerous spiral: the cost of high-quality care is extremely high, and parents struggle to afford it. In turn, providers do what they can to reduce parent cost, which often comes at the expense of child-care workers or program quality. Eventually, parents can no longer afford care, or the provider can no longer cover their expenses and the program closes.

Low- and middle-income families would see significant monthly savings with a federal policy that capped child-care costs at the 7% threshold. These savings could help families with necessities: affording rent, getting a checkup at the doctor or buying medication, making a utility payment, or purchasing healthy groceries for their children.

While existing initiatives, like the child care and development block grant program, distribute resources to states and low-income families, current funding is only sufficient to serve one in nine eligible children and the funds can’t be used to increase supply. Policy makers, advocates, and families agree that child care is the backbone of our economy, and that we need a significant, holistic, rather than piecemeal, investment to ensure the market does not collapse.

Federal investments are the only way to improve access, affordability, and quality. A comprehensive federal package would provide significant funding split between lowering costs for families, increasing compensation for teachers, and building capacity through new or expanded businesses.

Federal investments

By targeting all sides of the market, a federal investment would (1) put families within the recommended 7% cap on costs, collectively saving millions of dollars each year; (2) create millions of jobs with adequate pay and additional training and credentialing, to ensure that centers are staffed by qualified educators and reducing turnover; and (3) create a unified system that promotes parents’ choices of care for their children.

Through these investments, states could also create systems that track workforce data and bolster quality ratings, partner with local intermediaries to ensure that underinvested communities have access to expanded services, and guarantee centers receive financial support that reflects the true cost of care.

Recent polling shows that over half of all Americans support providing child care to help expand the economy’s productive capacity. And now with a supportive administration in the White House, Congress faces an opportunity to establish a unified child-care sector for the first time in American history. Comprehensive child care, as opposed to our current, fractured child-care system, could be revolutionary for families and support parents’, primarily mothers, and child-care professionals’ workforce participation—enhancing productivity, increasing economic growth and making U.S. markets more globally competitive.

Absent congressional intervention, economic challenges will continue to worsen. High costs, persistent low wages, and enduring workforce challenges prevent the child-care sector from recovering—or advancing—without action. Every American, in every industry, is affected by these losses.

Hailey Gibbs is a senior policy analyst and Maureen Coffey is a policy analyst with the Early Childhood Program at the Center for American Progress.