This post was originally published on this site

Welcome to Is This Working?, a column about the future of work through the lens of gender. That’s a question many workers, particularly women, are asking two years into a pandemic that has strained many systems to their breaking point, laid bare longstanding inequities, and prompted people to reevaluate what they want and need from work.

After the Great Recession in 2009, Black women’s employment didn’t recover for a decade. This has been the trend over the past 50 years: Unemployment among Black workers has recovered more slowly from recessions than that of their white counterparts.

The same is true this time. As the U.S. economy rebuilds in wonky pandemic conditions, Black women are again enduring a slow employment recovery and difficult labor-market outcomes. C. Nicole Mason, the president and CEO of the nonprofit Institute for Women’s Policy Research, worries that without significant action, “it’ll be déjà vu” — a replay of the Great Recession with some groups, particularly Black women, getting left behind.

Mason said she hopes the U.S. can change the trend this time around. “We have an opportunity to really dig a little bit deeper and address some of the structural and institutional barriers to workforce participation for people of color, and Black women in particular,” Mason said.

‘A red flag’ in the pandemic recovery

You’ve seen the sanguine headlines about job growth and a falling unemployment rate, showing the economy continues to rebound even with the Fed hiking interest rates to curb inflation. But topline economic snapshots hide the fact that many women of color, particularly Black women, aren’t recovering at the same pace.

Take February’s jobs report: While the overall U.S. unemployment rate fell from 4% in January to 3.8% in February, and the economy added 678,000 jobs, unemployment for Black women ticked up from 5.8% to 6.1%, the highest rate for women of any race or ethnicity. Some 31,000 Black women exited the labor force.

Black women, who have typically had the highest labor-force participation rates among women — owing, as economist Nina Banks puts it, to societal expectations of Black women as workers and discrimination against Black men in the labor market — saw their labor-force participation rate fall from 61.9% in January to 61.7% in February. In contrast, their pre-pandemic participation rate in February 2020 was 63.9%, the National Women’s Law Center notes.

Unemployment rates don’t include people who’ve left the labor force and are no longer job hunting — but if you were to count the 199,000 Black women who have left the labor force during the pandemic as unemployed, the unemployment rate for Black women would be 7.8% rather than 6.1%, according to the NWLC’s analysis.

“Black women aren’t sharing in this strong job growth, and that’s a red flag,” said Kathryn Zickuhr, a labor market policy analyst at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. “There’s a degree of volatility and unpredictability here that can be harmful for these workers and their families.”

The duration of unemployment for some groups is also a concern, Zickuhr says, pointing out that the average length of unemployment is 26.9 weeks for Black women and 30.7 weeks for Asian American women, compared to 24.1 weeks for white women. “That’s just among workers still in the labor force, and doesn’t capture those who have left,” she added.

‘Other parents are struggling just like I am’

Lafleur Duncan, a mother of two in Bushwick, Brooklyn, who had been a nanny for more than 30 years, lost her job in March of 2020 when the family she worked for moved away from the city. With the loss of her income — which made up the majority of her family’s earnings — and her husband working reduced hours at his job as a chef at a corporate building, the couple has struggled to afford food and the $2,400 monthly rent for their apartment in an affordable-housing building. The small business she started from their home has yet to get off the ground.

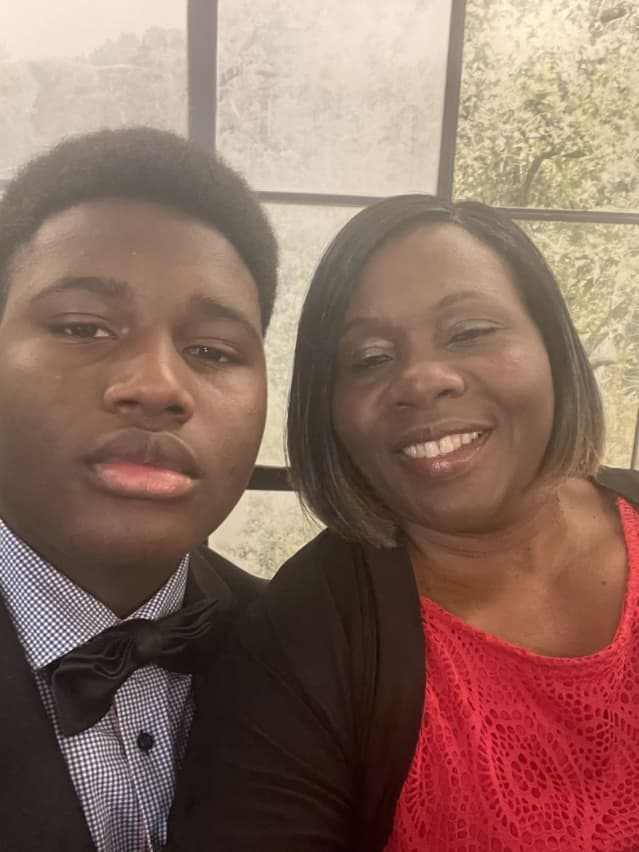

Lafleur Duncan with her 14-year-old son.

Courtesy of Lafleur Duncan

Duncan, 53, said she appreciates this opportunity to spend more time with her 14-year-old son and help with his virtual schooling. But the other side of the coin, she added, is “the strain of not being able to pay the rent, because there’s only one income at this time coming in.”

While Duncan was able to put monthly payments from the enhanced child tax credit last year toward asthma medication, college savings, and shoes and clothes for her rapidly growing teen — “It stopped a big hole in my family,” she said — those payments came to an end in December. (Duncan, a member of the grassroots organization MomsRising, has been an advocate for this relief.) She was also able to access emergency rental assistance through the city and has applied for cash benefits through the city as well. But her landlord plans to take her family to court over remaining back rent they owe.

“The struggle is real with us out here,” Duncan told MarketWatch. “I’m not the only individual; I’m not the only mother. … Other parents are struggling just like I am in the African-American community.”

‘Interlocking and amplifying’ forces fuel an unequal recovery

Structural weaknesses that drove lower wages and worse economic outcomes for Black women before the pandemic set the stage for the losses we see now, Zickuhr said. As a group, Black women workers experience “several interlocking and amplifying factors” that mean they’ve been more exposed to many of the pandemic’s harms, but are also less likely to have access to many of the supports that contribute to economic security and resiliency in the labor market.

For example, Black women experience discrimination in the workforce and in pay; often end up in low-wage work through occupational segregation; experience disparities in household wealth; and often have greater care responsibilities, Zickuhr said. While that’s not an exhaustive list, she added, these factors “connect and contribute to the challenges they face both during an economic crisis and during the broader economic recovery.”

Black women, along with Latinas, are overrepresented in sectors like leisure and hospitality, healthcare and retail, which were hit hardest by the pandemic, Mason noted.

“‘When they’re thinking about reentering the workforce, parents have to know and believe that they have reliable child care so they can sustain employment.’”

Although schools and daycares have reopened, Mason added, child care for many parents, especially those who must physically show up to a workplace to get paid, “remains unpredictable and unreliable.” Almost 16,000 child-care centers and home-based care programs shuttered between December 2019 and March 2021, translating respectively to a 9% and 10% loss, according to an analysis of available data by Child Care Aware of America, which advocates for access to affordable child care. Black, Latino and Asian families have been disproportionately impacted by child-care center closures.

As Child Care Aware points out, the U.S. already had an insufficient supply of high-quality child care pre-pandemic, particularly for Black and Latino families who — alongside structural obstacles that impact education, employment and access to services — are more likely than their white counterparts to work nontraditional hours. The pandemic has only worsened child-care supply problems, and labor-force exits associated with living with children have been more common among Black and Latina women, according to the Minneapolis Fed.

“When they’re thinking about reentering the workforce, parents have to know and believe that they have reliable child care so they can sustain employment,” Mason said.

Women, particularly women of color, are also more likely to work in care sectors that were harder hit by the pandemic and have not recovered. These jobs are often undervalued and provide low pay, due to what MarketWatch’s Jillian Berman describes as the industry’s “quirky economics,” as well as historical racial and gender discrimination. In fact, many of these workers can’t afford child care for their own kids.

Some entrepreneurship ‘borne out of necessity’

Another Great Recession-era trend: a surge in the number of businesses owned by women, particularly Black women and Latinas, between 2007 and 2012, according to a 2015 report by the National Women’s Business Council. Pre-pandemic, Black women were the fastest-growing group of business owners from 2014 to 2019.

Black business ownership fell most steeply compared to other groups in the pandemic’s early months (by 41%), and business owners of color struggled to access Paycheck Protection Program loans. Black women-owned businesses have also faced many challenges during COVID-19 with respect to capital, funding and consumer demands, but some data points suggest women of color, including Black women, have led the way in starting businesses during the pandemic. One NBER-distributed working paper found communities with greater shares of Black residents have seen higher relative increases in startup formation between 2019 and 2020.

Many of the same forces keeping Black women from an equitable pandemic recovery — labor-market discrimination, overrepresentation in sectors hit hardest by COVID-19, pay gaps and child-care challenges that leave them caring for kids at home — may also be driving some to launch businesses, said Mason and Saran Nurse, a postdoctoral fellow at Kean University who studies racial disparities in entrepreneurial outcomes.

“Some of this entrepreneurship is borne out of necessity,” Mason said.

Nurse, who until recently owned her own pet-care services business for 20 years, agreed. “It’s not necessarily a good thing that they are [being pushed toward entrepreneurship],” she said. “It’s not as if they’re pursuing it because of opportunity, because a lot of it is necessity-based.”

“Creating a more resilient economy and a true recovery for Black women — and for all workers — means making long-overdue investments in workers, families and communities.”

Black women-owned businesses often also struggle to keep their businesses afloat, Nurse added. This is due to a variety of factors, including lack of access to financial capital.

Duncan, for her part, said she had not experienced labor-market discrimination — but nonetheless feels like the pandemic’s circumstances pushed her into entrepreneurship. Business is slow so far, but she hopes the venture can lead to greater freedom with both her time and finances. She and her husband want to eventually buy their own house.

The pandemic, she said, “pushed me into seeing the fact that you don’t have to rely on others’ income.” “You can build for yourself,” Duncan said. “You can go out there and make things better for you and your family.”

Pre-pandemic baseline is ‘not necessarily the goal’

Relative to pre-pandemic levels, Black women’s employment continues to be the weakest compared with that of Latina and white women, and women’s employment overall hasn’t recovered as much as men’s, Zickuhr said. But the way things were right before COVID-19 wasn’t ideal either, she added, given the many workers experiencing wage gaps, occupational segregation and poor job quality.

“Where we were right before the pandemic is not necessarily the goal of where we want things to be, because that baseline has a lot of inequities built into it,” she said. “That would be, in one sense, recovery — but definitely not the finish line. We can still do much better.”

Creating a more resilient economy and a true recovery for Black women — and for all workers — means making long-overdue investments in workers, families and communities, Zickuhr said.

The list is long: There’s evidence that providing income supports, investing in child care, raising the minimum wage, strengthening anti-discrimination laws and enforcement, bolstering labor protections, and investing in paid family and sick leave would help, she said.

Democrats are working with the White House to rebrand parts of President Biden’s doomed “Build Back Better” social-spending and climate agenda as a strategy to lower rising costs and win over West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, the key Democrat holdout on the bill. Earlier versions of Build Back Better had included paid family leave, universal pre-K, large investments in child care, and an extension of the expanded child tax credit.

Advocacy groups like A Better Balance also say the bipartisan Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, which the House passed last May, would help keep pregnant workers in their jobs by requiring employers to provide reasonable workplace accommodations.

Some scholars, like Margaret Teresa Brower of Harvard University and Jamila Michener of Cornell University, have called for policies that are responsive to Black and Latina women’s specific economic experiences, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. Their research analyzing state-level policies during the tail end of the Great Recession and white, Black and Latina women’s economic well-being found that “policies have unequal consequences across subgroups of women,” and the relationship between public policies and economic status varies by race and ethnicity.

In a February 2021 Washington Post piece, Brower and Michener wrote that Biden’s actions to pause student-loan payments and evictions and expand access to insurance coverage were of particular importance to women of color. “If the Biden administration wishes to support economic stability and mobility for Black and Latina women, it could consider tailored federal legislation that pays attention to how policies affect women of color,” they added, noting that job-creating policies are “especially imperative.”

To be sure, no one policy can magically solve these issues, Zickuhr said.

“We’re talking about deep, systemic problems that have enabled and sometimes furthered discrimination and inequities in labor market outcomes for Black women and for their families,” she said. “We have a lot of evidence around these policies, and they often reinforce each other, which is one of the reasons why there’s no single lever to pull.”

A chance to renegotiate the terms of work

Women thinking about reentering the workforce are weighing flexibility, paid time off, healthcare and other benefits that contribute to economic security, Mason said. Before COVID-19, many women of color working in what were not considered “good jobs” were “just making do, trying to figure it out,” she said. “But post-pandemic, we understand — and it’s not just women of color — that it makes a difference: My wages make a difference; whether I have paid sick or family leave; healthcare. It’s all these things together.”

That’s why the so-called war for talent right now is good not just for white-collar workers, but for all workers, because it gives people an opportunity to renegotiate the terms of work, Mason said. Many workers have capitalized on the current tight labor market to secure better wages and benefits, though some early evidence suggests that it hasn’t necessarily helped service workers secure lasting gains with respect to wages and predictable hours, as inflation persists and employers continue to rely on part-time scheduling.

Mason says companies now have an opportunity to ensure they’re providing workers with good benefits, competitive pay, and dignity and respect that makes them feel like their skills and talents are being used.

“Right now, there are a lot of businesses that fall short in one of those three areas,” she said. “And some companies, in the absence of federal action, are raising wages. They’re examining their workforce policies and practices. They are leading and serving as models for how we can shift in this moment.”