This post was originally published on this site

“Gas is just a ripoff,” the guy at the table next to me at Starbucks said to his pal, as he sipped whatever he was drinking. Even if it was the cheapest thing on the menu —plain, old Pike Place coffee — it costs, at $2.85 plus tax for a 16-ounce grande, the equivalent of about $23. Now that’s a rip off.

But it’s gas we complain about. The average price of regular gas nationwide on Monday $4.06 a gallon, according to AAA. When it hits $4.11 — maybe today — the media will call it an “all-time high,” but the truth is when adjusted for inflation, the all-time high would now be $5.37. In other words, we’ve seen worse.

Marching in lockstep with the complaining is the closely watched Baker Hughes rig count, which tracks the number of oil rigs in operation in the United States and elsewhere. As of March 4, that number was 1,680, up 35% from a year ago. The bulk of this increase, by the way, was in the U.S. and Canada.

That’s the market at work. Oil (West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. benchmark) was $64 a year ago on the NYMEX; this morning it was $126

CL.1,

Brent crude was $130. Thus more rigs are coming back online as producers take advantage of higher global prices.

And why are prices higher? Because Russian supply is being knocked out of the global market. In 2020 we got 7% of our imports from Russia. But between increased drilling here at home and reliable friends in Canada and Mexico — which together supply about two-thirds of all U.S. crude imports — we can easily replace Russia’s supply. But U.S. drillers, mindful of the slew of bankruptcies which happened the last time they overdrilled — just two and three years ago — must balance their greed with caution.

Returning to Putin, we can put the screws to him in other ways. President Biden, whose leadership during this Russia-Ukraine crisis has won even Republican praise, dispatched an envoy to Venezuela last week to discuss easing U.S. sanctions and helping that South American oil giant boost exports. The Trump administration cut off ties with Venezuela in 2019 over concerns of, ironically, electoral fraud, but we have bigger fish to fry now.

U.S. officials have also been visiting Gulf sheiks in the Middle East to solicit their help as well. What about Saudi Arabia? Riyadh has indicated that they intend to stick by previous OPEC plans for a small output rise in April, but not on the scale of what the U.S. wants. This has led to talk, first reported by Axios, that Biden himself might go to Saudi Arabia in April. This would be a mistake. The president of the United States is no one’s suppliant.

Iran is also part of this global Rubik’s cube. Even as we spar indirectly with the Russians, we’re working with them, China, Britain, France and Germany (the so-called “P5+1” group) to revive the 2015 agreement to limit Tehran’s nuclear program. It’s believed that Iran’s bomb-making capacity has accelerated since then-President Donald Trump unilaterally pulled out of the agreement in 2018; constraining it is something that the Washington, Moscow and Beijing and the others have in common.

Here’s how a new Iran deal could squeeze Putin. Iran has offered to restrict its enriched uranium production — the key to a nuclear warhead — and centrifuge testing, and also allow western inspections. In exchange, Iran would get sanctions relief and the ability to sell more oil.

Increased global supply, the thinking goes, would offset Russia and eventually lower global prices. In turn, Tehran will restrict its enriched uranium production and centrifuge testing and accept enhanced international inspections. The U.S. gets to hurt Russia while tightening the leash on Iran. At least that’s the theory.

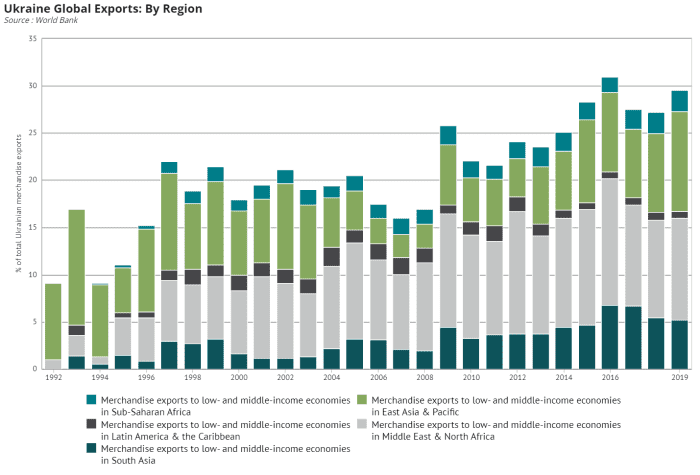

Energy isn’t the only thing that has been disrupted by Putin’s war. Russia and Ukraine together export — or used to — about a quarter of the world’s wheat. The bulk of this has traditionally gone to the Middle East and North Africa.

But the Ukrainian government Sunday announced that it will suspend agricultural exports. The timing couldn’t be worse. Drought (climate change?) has meant crop reductions in countries like Iran, Syria, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt, says U.S. Wheat Associates, a trade group, and thus higher prices. This is on top of existing strains from pandemic/supply chain issues. As we saw with the Arab Spring revolts of a decade ago — which were largely sparked by rising goods prices — we could see new unrest in these parts of the world.

These sorts of problems — global competition for energy, food, and, increasingly, water — dovetail with long-running CIA and Pentagon analyses of how regional and global instability can increase.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made it all worse. Americans must understand — as higher food and energy prices have painfully shown — that we are hardly immune from such troubles.