This post was originally published on this site

With the Federal Reserve all but certain to begin raising interest rates in March, market prognosticators have been quick to reassure investors that history shows stocks tend to do just fine as policy makers embark on a monetary policy tightening cycle.

But like most things related to markets, there’s more to the story.

It turns out that when the Fed moves fast to hike rates, as it has signaled it’s prepared to do in a scramble to rein in U.S. inflation running at its hottest since the early 1980s, the stock market’s short-term performance hasn’t been quite as stellar, said Ed Clissold, chief U.S. strategist at Ned Davis Research.

“It’s intuitive that the Fed’s job when they start to raise rates is to take the punch bowl away before the party gets going too much,” he said, in a Thursday interview. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that “the quicker they’ve been, the more markets have taken note.”

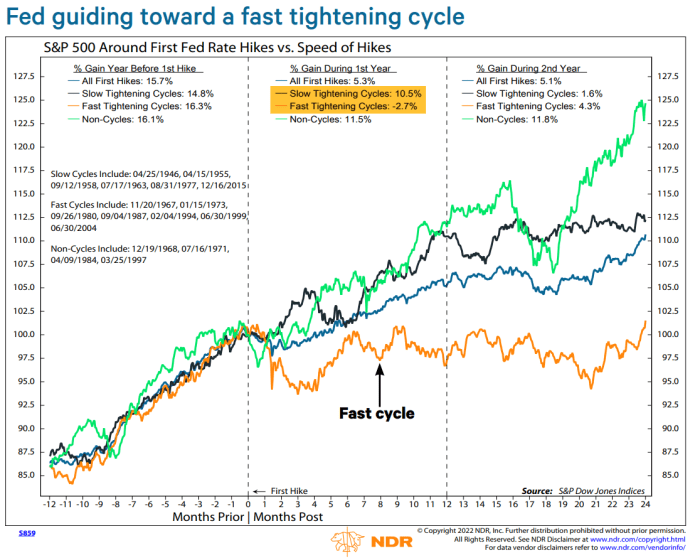

Clissold and Thanh Nguyen, NDR’s senior quantitative analyst, detailed the difference between market performance in “fast” versus “slow” cycles in a Feb. 9 note. They found that in the year following the initial rate increase, the S&P 500

SPX,

rose an average 10.5% in slow cycles versus an average fall of 2.7% in fast cycles (see chart below).

Ned Davis Research

The median gain during the first year of a slow cycle was 13.4% versus 2.4% for fast cycles. The median maximum drawdown in slow cycles was 11%, compared with 12.1% for fast cycles.

Overall, the “return and drawdown statistics of a fast cycle are consistent with choppy conditions, but not necessarily a major bear market,” Clissold and Nguyen wrote.

So how fast is fast? It’s a bit subjective, Clissold told MarketWatch, but past cycles have shaken out relatively clearly between the two categories. NDR expects four or more rate increases over the Fed’s seven remaining policy meetings in 2022 alongside the start of a reduction in the size of the central bank’s balance sheet — a pace that would put the cycle clearly in the “fast” category.

Some Fed watchers see a faster pace than that, and fed-funds futures traders have increasingly priced in the prospect of policy makers kicking off the cycle with a half-point rate increase rather than the typical quarter-point, or 25 basis point, move.

The market’s pricing of an aggressive rate-hike scenario appears reasonable given the inflation picture, said Lauren Goodwin, economist and portfolio strategist at New York Life Investments.

That said, it’s worth remembering that both the market and the Fed itself, via the central bank’s so-called dot-plot forecast for benchmark interest rates, have been relatively poor at predicting the actual rate outcome, she noted, in a phone interview.

That isn’t a criticism, she said. Rather it merely reflects just how difficult it is to make accurate rate predictions. New York Life Investments, for its part, looks for four quarter-point rate increases in 2022, possibly frontloaded.

The point, she said, is that there has already been substantial volatility around rate expectations and, moreover, that’s likely to continue as data comes in. That could make for more volatility in the rates market and the yield curve, which has flattened significantly since the beginning of the year as rates at the short end have risen sharply in anticipation of Fed tightening while longer-dated yields have risen less sharply.

The yield curve is viewed as an important indicator in itself. An inversion of the curve, particularly when the 2-year or shorter-dated yields rise above the 10-year yield, has been a reliable recession indicator.

That hasn’t happened yet, but the rapid flattening of the curve may reflect fears aggressive Fed tightening could throw the economy into recession, some analysts say. Others offer a more benign interpretation, with the flattening reflecting expectations a quick response by the Fed will help wrestle down inflation without requiring rates to rise to eye-watering levels.

On the surface, the latter scenario would seem to favor stocks of companies tied to the economic cycle, particularly those that are able to pass on rising costs and navigate rising capital costs, Goodwin said. In asset class terms, that would tend to favor value stocks over growth stocks, she said.

But it’s not that simple. “It really depends on the company and that their capital structure and competitiveness in this type of environment,” she said, noting that some technology stocks have fared very well in an environment that seems to no longer favor growth, while others have suffered.

That makes for a more “company by company” picture that favors active managers, Goodwin said.

It’s all part of a “midcycle” environment. Economic growth remains healthy, which is constructive for stocks, but growth is only likely to slow from here, she said, and that makes “earnings and earnings quality particularly important.”

That will change when there are clearer signs the economy is simply decelerating, which is when more broad level asset class considerations play a bigger role in determining outcomes for investors, she said.

U.S. markets will be closed Monday for the Presidents Day holiday. Meanwhile, investors, like Fed officials, will remain glued to inflation data, while keeping watch on developments around Ukraine as U.S. officials warn of the threat of a Russian invasion.

See: What a Russian invasion of Ukraine would mean for the stock market, oil and other assets

Ukraine-related jitters were blamed in part for the stock market’s stumble over the past week, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

falling 1.9%, while the S&P 500 fell 1.6% and the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

lost 1.2%.

Friday will bring the Fed’s favored reading on price pressures with the release of the January personal consumption and expenditures, or PCE, inflation reading. The University of Michigan’s final February take on five-year consumer inflation expectations is also due Friday.