This post was originally published on this site

It’s been months since LaJoy Johnson-Law stayed within her grocery budget — but that’s not for a lack of trying in a time of high inflation.

When Johnson-Law shops for herself and her daughter, her goal is to spend a monthly maximum of $300. In December, the Washington D.C. mother spent $350. In January, she spent $400.

It’s not looking good for February. Last week, Johnson-Law walked into her Giant supermarket with a plan: spend no more than $100. Her bill was $165.

“My dollar isn’t working as hard. Even this last trip, I didn’t get much, it wasn’t a lot and I spent $165,” said Johnson-Law, 33, who works at a nonprofit helping families navigate the Washington, D.C. school system as she also pursues a master’s degree in public policy and administration.

Because Johnson-Law’s dollar isn’t going as far, she’s making an extra effort to contain costs. She makes careful lists and schedules her grocery store trips in advance to cut down on the chances of making impulse buys.

And after checking to make sure the ingredients are comparable, Johnson-Law increasingly opts for the store brand, also called the “private label” version, instead of the brand name product.

Her recent $165 grocery tab included an off-brand ketchup, oatmeal and a generic version of the Cap’n Crunch cereal that tastes just as good to Abria, her 10-year-old daughter. “There’s no need for a name brand,” Johnson-Law said.

It’s a shopping strategy more people may be considering at a time when inflation rates are at 40-year highs. So how much money can a person save these days by choosing the no-frills generic instead of the brand-name product?

Sometimes a lot, but not always, data show.

LaJoy Johnson-Law and her daughter, Abria. On a recent trip to the supermarket, she saved money by buying off-brand ketchup, oatmeal and cereal. ‘There’s no need for a name brand,’ she said.

Photo courtesy LaJoy Johnson-Law

Consider Johnson-Law’s store brand Cap’n Crunch

PEP,

Cereals are categorized as grocery purchases, according to NielsenIQ, a consumer data analytics company. Salad dressing, canned goods and products with long shelf lives also count as grocery purchases.

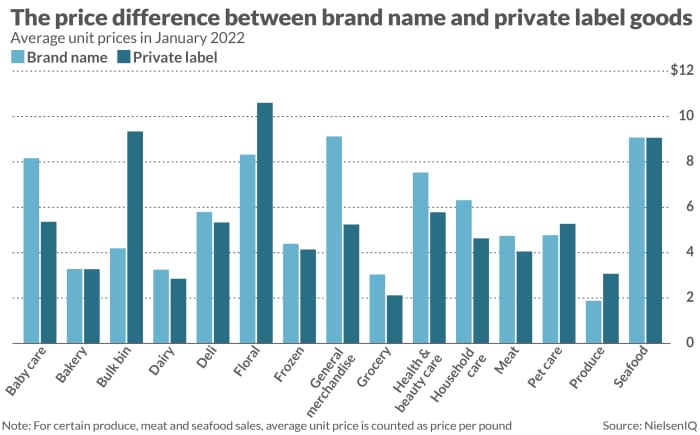

Brand-name grocery products in America had a $3.04 average unit price in January while off-brand or private label grocery products had a $2.12 average unit price last month, according to NielsenIQ data.

The average unit price on dairy, like the milk for Johnson-Law’s cereal, was $3.25 for brand name in January and $2.85 for private label, NielsenIQ said.

But there’s essentially no difference in price on seafood, at least during January. It was a single penny difference between the $9.07 average unit price for brand name and $9.06 for store brand seafood, the numbers showed.

For some purchases, the brand name can be cheaper: the January average unit price of brand-name produce was $1.88 compared to the $3.07 for private label. For fresh flowers and anything else in NielsenIQ’s floral category, the average unit price on brand name was $8.32 versus $10.60 for the private label.

Keep in mind a unit would be anything with a barcode, so that could be a generic item purchased in bulk, or it could be smaller brand name item. But the numbers show the cost savings from private-label goods aren’t automatic.

The NielsenIQ numbers show costs creeping up for both private label and name brand goods. For example, the January average unit price on brand name groceries is up 9.6% year over year and up 8.2% for private label groceries in that same time.

“Despite the fact that consumers are often mindful of their spending, meaning they seek good value for a good price, NielsenIQ research shows that consumers, particularly those in developed markets, are willing to pay more for unique products that boast a point of differentiation and delivers on that promise,” said Carman Allison, NielsenIQ’s vice president of thought leadership.

Private-label goods are making inroads in consumers’ wallets, Allison noted. Many see these off-brand goods as perfectly fine substitutes or equivalents. “Consumers are making category-by-category decisions, and retailers and brands need expertise to understand consumers in every single category,” he said. “In many markets, private-label offerings are becoming a local alternative to premium.”

Polling and market data paint a mixed picture on whether people are going more for private label products instead of the brand name. Off-brand product sales are growing, but it’s possible people are buying the brand name and off-brand version too.

Shoppers bought $13.8 billion in private-label goods during January, according to NielsenIQ data. That’s a 4.2% increase from the same point last year. But shoppers also purchased $61.9 billion in brand-name goods in January, NielsenIQ data showed — a 6.6% year-over-year increase.

Three in 10 consumers say they are buying more store-brand food and drinks compared to a year ago, according to an almost 2,000-person poll from Mintel, a market research firm. But almost two-thirds (65%) say they’re buying the same amount, said the poll, conducted in December. When people buy store-brand goods, almost half (47%) say it’s because of “rising food/drink prices.”

Sodas and cereals are the purchases where polled consumers said they prefer going name brand, at 63% and 60% respectively. The name-brand preference is weakest for frozen vegetables (31%) and fresh produce (28%).

‘Milk is milk. Eggs are eggs.’

In the suburbs of Austin, Texas, Terry Carter, a self-described “cheap son of a gun,” has been buying mostly off-brand goods for three decades — a necessity as he raised six kids. “You gotta look at cost savings to cut every corner,” said Carter, 57, who handles development and operations for a real estate company’s back office functions.

When he’s not expecting any particular flavor, he buys off-brand. “Milk is milk. Eggs are eggs,” said Carter. The same goes for products like chicken, lunch meat and also generic medication. He often starts with lower cost, off-brand home improvement tools at Harbor Freight . Carter considers buying the brand name if the tool breaks and he’s planning on using it a lot.

Terry Carter is a longtime buyer of off-brand products. ‘You gotta look at cost savings to cut every corner,’ the father of six said.

Photo courtesy Terry Carter

The Aldi discount grocery store that recently opened nearby has been a real find, Carter noted. He doesn’t pass up the $4 protein shakes at the store. That’s at least two dollars less than comparable shakes at a Walmart

WMT,

he said.

But Carter has his limits for bargain-seeking, like when his wife bought off-brand canned soup. “Nope, we’re going back to Campbell’s

CPB,

Some generic can be too generic,” Carter said. “When I go brand, I’m buying the quality or the flavor. That’s what the brand is.”

The looming question is whether rising prices are going to force consumers to put their money concerns ahead of their allegiances to certain brands and flavors, and to what extent?

Student loan payments are slated to resume in May. The last of the advance child tax credit payments hit bank accounts in December. Almost half (47%) of parents say the payment’s absence will have a “major impact” on their finances, according a poll this month from the National Parents Union. And then there’s the question how long high inflation sticks around.

Darren Seifer, food and beverage industry analyst at the NPD Group, a market research company, hasn’t yet seen consumers swapping brand name for off-brand bargain products on a mass scale during the pandemic. But 2022’s conditions are ripe for some to make that switch. “I think this is the year people make that decision where they spend their food dollars,” Seifer said.

The lapse in the child tax credit payments intensify inflation’s pinch on Johnson-Law, who makes between $35,000 and $40,000 annually. When she went over budget on groceries in December, her $250 payment took some of the sting out.

“It’s really disheartening to know that, as we are trying get out of COVID, to have an increase in prices, but to take away resources,” she said.

For now, Johnson-Law said she’ll hang on with her cost-limiting strategies as best she can, which includes keeping her eyes open for cheaper off-brand products.

She’ll also have to reconsider her expectations on household expenses. “I need redo my budget.”