This post was originally published on this site

There’s mounting evidence that the historical returns private equity (PE) has produced aren’t as good as they otherwise seem, and that, in any case, its future returns are unlikely to be as good as in the past. In addition, there may be public-market alternatives that can be expected to perform almost as well — if not better.

Up until now, PE was of little more than academic interest to most retail investors. It was the exclusive province of large institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments. But this is beginning to change. Mutual fund giant Vanguard Group since 2020 has created two private equity funds, and the first was closed within a year after attracting twice as many assets as originally targeted. More such funds are surely on the way.

Ironically, just as the PE world is beginning to open up to individual investors, it’s looking less attractive. This is partly because PE’s historical returns are being reassessed, and partly due to headwinds that will make it difficult for PE to produce returns in the future that are as good as those in the past.

Private equity’s past performance

Recent research has uncovered the outsized role that various methodological assumptions play in calculating PE funds’ returns. One study, for example, found that some PE funds increased their reported returns by 2.6 percentage points simply by changing how they accounted for money that investors had committed to investing in those funds but not yet paid in. Another study analyzed the valuations of so-called unicorn s— private companies reportedly worth more than $1 billion. The authors found that, using these companies’ own internal documents, their reported valuations on average were 50% above actual, or fair, value. This study illustrates the large leeway that PE funds have in calculating their net asset values.

Some researchers I interviewed believe that, when correcting methodological biases, PE funds don’t outperform public markets. Other researchers I interviewed disagreed. There’s no way in this column I can do justice to this debate, much less determine which side is right. But the very existence of this methodological dispute should give you pause. If PE funds can be shown to have both beaten the public market and to have lagged it, depending on how their returns are calculated, then PE might not be all that it’s cracked up to be.

Future performance

Regardless of how PE has performed in the past, serious doubts can be raised about whether it will perform as well in the future. One who harbors these doubts is Christopher Tessin, the founder and managing partner of Acuitas Investments, a Seattle-based firm that focuses on micro-cap stocks — those with market caps of about $1 billion or less. Many of the stocks his firm has invested in have been bought out by PE firms, so Tessin is familiar with the industry.

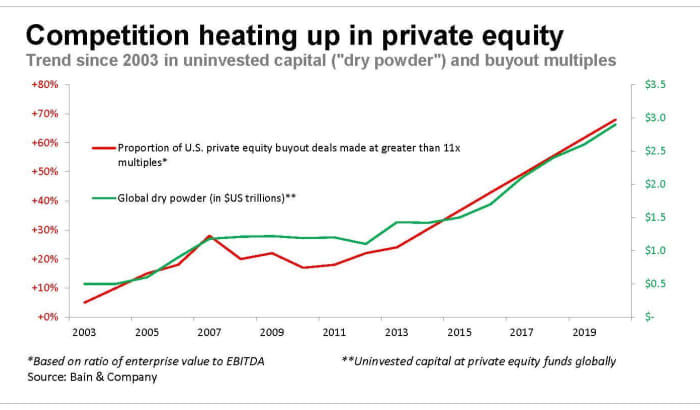

In an interview, Tessin identified several sources of headwinds that he expects PE to face in coming years. Perhaps the biggest is the sheer amount of uninvested cash that PE firms have — so-called “dry powder.” Tessin predicts this will create increasingly intense competition among PE funds, leading them to pay higher and higher premiums when buying out public companies and taking them private. That in turn will reduce their profit when they eventually sell those companies.

To put this headwind in context, consider data from the latest “Global Private Equity Report” from Bain & Company. The firm reports that global dry powder now stands at close to $3 trillion, versus $0.5 trillion in 2003. Coincident with this increase has been a big jump in the multiples of cash flow that PE firms pay when acquiring companies. In 2003, fewer than 5% of U.S. buyout deals were made at greater than 11 times cash flow, according to Bain. The comparable proportion today is more than two-thirds, as you can see in the chart below.

Microcap advantage

Tessin says he expects this increase to continue, with the consequence that microcap stocks will become a more compelling investment than PE itself. His reasoning is that such stocks are typically the buyout targets of PE firms, so the higher multiples that PE firms must pay will shift the investment landscape away from being a buyer’s market favoring PE to a seller’s market that favors microcap stocks.

Diversification is especially important when investing in microcap stocks, since there is a wider distribution of returns in this corner of the market than among larger-cap stocks. One way to gain that diversification is with an index fund, such as the iShares MicroCap ETF IWC, which is benchmarked to the Russell Microcap index.

“Nearly two thirds of all public companies that were M&A targets over the last decade have been microcap companies,” Tessin says. Plus, “over the past decade, more than one-third of the Russell Microcap Index’s entire return has been from companies that were acquired.” Tessin says he wouldn’t be surprised if this proportion becomes even higher in coming years.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.

More: These eight stocks — all highly indebted — may benefit most from higher inflation

Also read: This market-timing model has made stock investors more money than the ‘Super Bowl Predictor’