This post was originally published on this site

You almost certainly are too optimistic about how fast your retirement portfolio will grow.

And that could cause grave problems for you in coming years. A too-high return assumption leads you to withdraw too much from your portfolio early in your retirement—thereby shortchanging your later years.

This is why a realistic rate of return is perhaps the most important single input to a sound financial plan. Unfortunately, given our tendency to extrapolate the recent past into the future, stocks’ and bonds’ extraordinary returns in recent years have encouraged many of you to be even more unrealistic than you were before.

The reason to avoid extrapolating the recent past into the future is most easily understood as it applies to the bond market. Bonds have produced impressive returns over the last couple of decades as interest rates have declined, but only if rates decline as much over the next couple of decades would you be justified in extrapolating this past experience into the future.

Most of you can readily appreciate why that is unrealistic. If anything, you want to do the opposite of extrapolating: Given today’s historically low interest rates, probably the most realistic long-term return expectation for the fixed income portion is that, at best, they will merely keep even with inflation—and more likely produce significant losses.

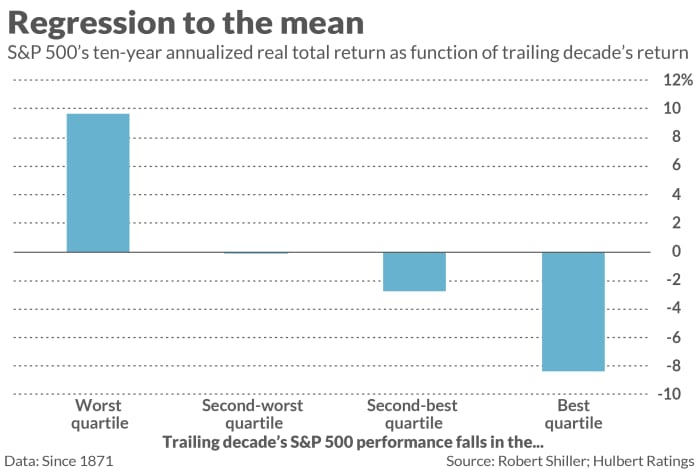

A similar pattern applies to the stock market. Take a look at the accompanying chart, which reports the S&P 500’s

SPX,

10-year real total return as a function of how it did over the trailing 10 years. I constructed this chart based on all rolling 10-year periods since 1871, courtesy of data from Yale University finance professor Robert Shiller.

Notice that the best average returns occurred after 10-year periods in which stocks performed most poorly—and vice versa. The negative correlation in the chart is significant at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is genuine.

Extrapolation bias

These statistics are sobering enough, but most investors make matters worse. Instead of appreciating that the correlation is negative, they instead assume it is significantly positive. The source of their error is a cognitive bias known as extrapolation bias—sometimes known as recency bias: We overweight recent events, and downplay long-ago history, when forming our projections of what’s to come. This behavioral tendency is why investors tend to be overweight at market tops and underweight at bottoms.

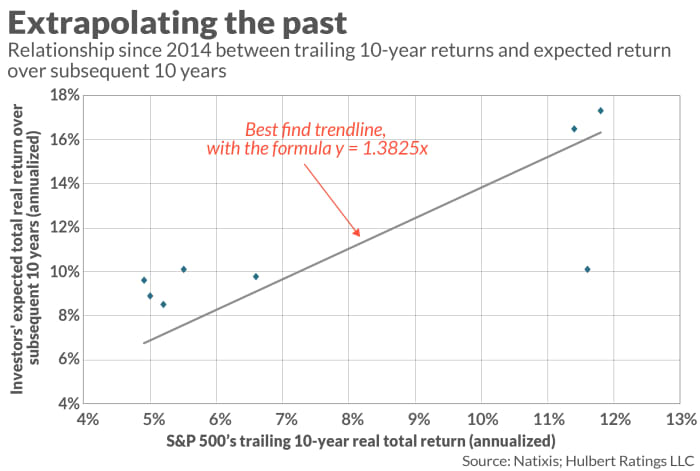

Recency bias is evident in investor expectations. Consider the responses to Natixis’ annual “Survey of Individual Investors.” Each year, one of the questions the firm poses to respondents is: “What are the real annual returns (above inflation) you expect to achieve in the long term?” On average since 2014, their answers have been higher when the stock market’s trailing returns were also higher. That’s just the opposite of the negative correlation I found between the S&P 500’s forward and trailing 10-year returns.

This positive correlation between trailing returns and expected future returns is plotted in the accompanying chart. Notice the best-fit trendline in the chart, which not only is positive but steep. In fact, the formula for this trendline indicates that investors’ expectations grow faster than do past returns. In other words, as past performance improves, investors become even more bullish.

According to the most recent Natixis survey, U.S. investors currently are expecting that their portfolios will enjoy a long-term real return of 17.3% annualized. That’s nearly triple the 6.1% annualized real return the U.S. equity market has produced over the last two centuries. Furthermore, as shown in the first chart above, we’re unlikely to even do as well as this historical average over the coming decade.

A bull market is the ideal time to subject your retirement plan to a reality check. Err on the side of being too conservative. The downside of doing that is that, in your later retirement years, you have more in your portfolio than you otherwise were projecting. That would be a nice problem to have.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.