This post was originally published on this site

Value stocks on average over the past century have significantly outperformed growth stocks — a pattern known as the “value effect.” But value has topped growth for a lot longer than we knew.

New research should go a long way to persuading skeptics that the value effect is genuine. Entitled “The Cross-Section of Stock Returns before 1926 (And Beyond),” the study was conducted by Guido Baltussen, Bart van Vliet and Pim van Vliet of Robeco Quantitative Investments in the Netherlands. To study the pre-1926 period, the researchers first had to create a database of individual stock prices, dividend yields and market capitalizations for the 61 years from January 1866 to December 1926. As you can imagine, this was a monumental undertaking, involving painstakingly hand-collecting the data. As far as they know, they are the first to create such a database.

Test of time

Armed with this data, the researchers were able to measure how value stocks performed relative to growth stocks in this never-before-studied period.

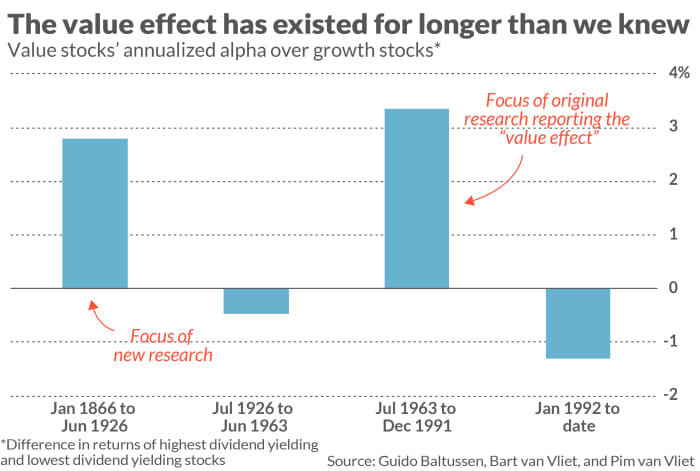

To understand what they found, it’s important first to review what, up until now, has been known about the long-term returns of value- and growth stocks. The original research to document the value effect, published in the early 1990s, covered the period back to mid-1963; it was conducted by University of Chicago professor (and Nobel laureate) Eugene Fama and Dartmouth College’s Ken French. They found that, over the period studied, value stocks significantly outperformed growth stocks, on average.

The gold standard in statistical analysis is to subject this original finding to out-of-sample tests, since that helps eliminate the possibility that the original finding was the result of data mining. The first out-of-sample test occurred when the professors subsequently extended their analysis back to 1926. The second out-of-sample test covers the period since 1991. Over both of these periods the value effect was weaker than in the 1963-1991 period.

There have been additional out-of-sample tests that focused on non-U.S. stocks, though some have questioned whether these other tests truly are “out of sample.” That’s because the international equity markets are considerably integrated, with the result that different countries’ returns may be significantly correlated.

This discussion sets the context for what this new research found. By analyzing the value effect over a lengthy period of stock market history that has never before been studied, the researchers conducted what arguably is the most significant out-of-sample test of the value effect.

Value wins

The researchers found that the value effect was markedly strong over the 1866-1926 period. It was far stronger than in the 1926-1963 and the post-1991 periods, and almost as strong as in the period that was the focus of the original Fama-French research. (See chart, below.)

Note that the researchers were unable to measure the value effect back to 1866 using the price-to-book ratio, the indicator Fama and French based their analyses on and which has become the standard metric for differentiating value from growth. But data on the book values of publicly traded companies don’t exist back to 1866. As Baltussen pointed out in an email: “U.S. companies listed on the NYSE [New York Stock Exchange] were only required to publish audited accounting statements as of 1932.”

As a proxy for value, the researchers instead relied on the dividend yield. Stocks with the highest yields were considered value, while the lowest-yielding stocks were put into the growth camp. Baltussen says that “though the lists of value and growth stocks constructed with the dividend yield are not identical to those constructed using the price-to-book ratio, there is a high degree of overlap.”

The bottom line of this new research? The value effect rests on a far stronger historical foundation than previously known. Even if value continues to lag growth for a while longer, as it has on balance over the past 15 years, we can be more confident than previously that the value effect eventually will eventually reassert itself.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: This market-timing model has made stock investors more money than the ‘Super Bowl Predictor’

Also read: These eight stocks — all highly indebted — may benefit most from higher inflation