This post was originally published on this site

Investors on Friday got a taste of the sort of market shock that could come if Russia invades Ukraine.

The spark came as Jake Sullivan, the White House national security adviser, warned Friday afternoon that Russia could attack Ukraine “any day now,” with Russia’s military prepared to begin an invasion if ordered by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

U.S. stocks extended a selloff to end sharply lower, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

dropping more than 500 points and the S&P 500

SPX,

sinking 1.9%; oil futures

CL.1,

surged to a seven-year high that has crude within hailing distance of $100 a barrel; and a round of buying interest in traditional safe-haven assets pulled down Treasury yields while lifting gold, the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen.

Putin and U.S. President Joe Biden were slated to talk by phone Saturday in an effort to defuse tensions.

Analysts and investors have debated the lasting effects of an invasion on financial markets. Here’s what investors need to know.

Energy prices set to surge

Energy prices are expected to soar in the event of an invasion, likely sending the price of crude above the $100-a-barrel threshold for the first time since 2014.

“I think if a war breaks out between Russia and Ukraine, $100 a barrel will be almost assured,” Phil Flynn, market analyst at Price Futures Group, told MarketWatch. U.S. benchmark oil futures

CL00,

CLH22,

ended at a seven-year high of $93.10 on Friday, while Brent crude

BRN00,

BRNJ22,

” the global benchmark closed at $94.44 a barrel.

“More than likely we will spike hard and then drop. The $100-a-barrel area is more likely because inventories are tightest they have been in years,” Flynn said, explaining that a monthly report Friday from the International Energy Agency warning that the crude market was set to tighten further makes any potential supply disruption “all that more ominous.”

Beyond crude, Russia’s role as a key supplier of natural gas to Western Europe could send prices in the region soaring. Overall, spiking energy prices in Europe and around the world would be the most likely way a Russian invasion would stoke volatility across financial markets, analysts said.

Fed vs. flight to quality

Treasurys are among the most popular havens for investors during bouts of geopolitical uncertainty, so it was no surprise to see yields slide across the curve Friday afternoon. Treasury yields, which move the opposite direction of prices, were vulnerable to a pullback after surging Thursday in the wake of a hotter-than-expected January inflation report that saw traders price in aggressive rate increases by the Federal Reserve beginning with a potential half-point hike in March.

Analysts and investors debated how fighting in Ukraine could affect the Federal Reserve’s plans for tightening monetary policy.

If Ukraine is attacked “it adds more credence to our view that the Fed will be more dovish than the market currently believes as the war would make the outlook even more uncertain,” said Jay Hatfield, chief investment officer at Infrastructure Capital Management, in emailed comments.

Others argued that a jump in energy prices would be likely to underline the Fed’s worries over inflation.

Stocks and geopolitics

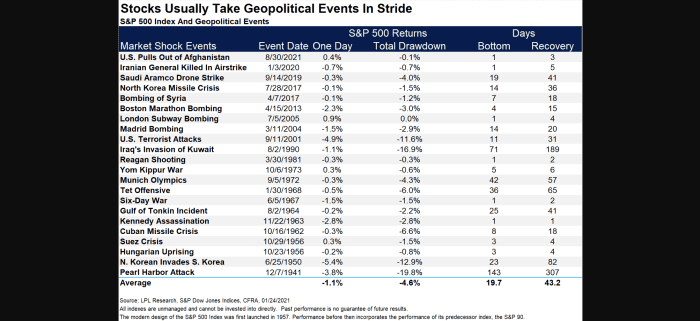

Uncertainty and the resulting volatility could make for more rough sledding for stocks in the near term, but analysts noted that U.S. equities have tended to get over geopolitical shocks relatively quickly.

“You can’t minimize what today’s news could mean on that part of the world and the people impacted, but from an investment point of view we need to remember that major geopolitical events historically haven’t moved stocks much,” said Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist at LPL Financial, in a note, pointing to the chart below:

LPL Financial

Indeed, the takeaway from past geopolitical crises may be that it’s best not to sell into a panic, wrote MarketWatch columnist Mark Hulbert in September.

He noted data compiled by Ned Davis Research examining the 28 worst political or economic crises over the six decades before the 9/11 attacks in 2001. In 19 cases, the Dow was higher six months after the crisis began. The average six-month gain following all 28 crises was 2.3%. In the aftermath of 9/11, which left markets closed for several days, the Dow fell 17.5% at its low but recovered to trade above its Sept. 10 level by Oct. 26, six weeks later.