This post was originally published on this site

In 1997, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution guaranteed every child, no matter how wealthy or poor, the right to what it calls a “sound basic education.” The state wasn’t allocating enough money to achieve that goal, the court found, and would need to increase funding accordingly.

Twenty-five years later, Judge David Lee had enough.

Because North Carolina has failed for years “to remedy the constitutional violation as the Supreme Court ordered, this Court must provide a remedy through the exercise of its constitutional role,” he wrote in a November court order.

“Otherwise, the State’s willful failure to meet the minimum standards for effectuating the constitutional right to obtain a sound basic education will threaten the integrity and viability of the North Carolina Constitution.”

Lee further escalated matters by taking the unusual step of ordering the state’s budget director, controller, and treasurer to distribute $1.7 billion from the general fund to statewide education departments.

He acknowledged the separation of powers of the three branches of government — namely that the legislature, made up of elected representatives of the people, controls the public purse. Still, “the orders of our Supreme Court are not advisory,” Lee added. “This Court can no longer ignore the State’s constitutional violation.”

Nearly three decades after it began, a legal standoff over adequate funding for education has devolved into what some observers consider a state constitutional crisis. The drama in North Carolina, often referred to in shorthand as the “Leandro case” may be a particularly extreme example, but it still highlights the often grim state of how public education is financed in America.

Woes precede pandemic

While many Americans assume education funding happens at the community level, it’s actually a state matter, said David Sciarra, executive director of the Education Law Center, a national research and advocacy group.

“When you think about public education finance, you should be thinking about states and asking whether elected representatives are providing sufficient state funding to support a system that provides meaningful opportunities for all children,” Sciarra told MarketWatch. “And the answer is that the states have done, and continue to do, a wholly inadequate job of funding public education. This isn’t new. In many states, we’ve had decades of chronic and severe underfunding of public schools.”

Everything laid bare by the pandemic, Sciarra contends, from teacher shortages to low morale and questions about leadership, is “beside the point.”

Addressing those issues is “not going to solve the problem, and it’s going to continue to distract us from what needs to be done, which is to hold legislatures to account for the deplorable ways these schools are funded. We’ve got to reckon with this as a nation.”

The legal battle in North Carolina began in 1994, when representatives of five lower-income school districts filed a lawsuit against the state, charging that it was violating the constitutional right to a “sound basic education.” (Each state has its own constitutional language, including “thorough and efficient” in New Jersey, and “uniform, efficient, safe, secure, and high quality” in Florida.)

But in the years after the 1997 ruling, North Carolina was repeatedly found to be out of compliance: failing to uphold its own constitution. In 2015, a judge ordered parties to come to “a definite plan of action,” and in 2017, all parties agreed to accept the recommendations of a consultant called WestEd, which worked with the input of two local policy groups to produce a report the following year.

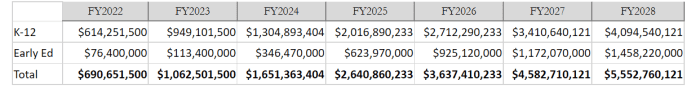

WestEd’s plan laid the groundwork for a 2021 agreement that envisioned the state slowly ramping up its expenditures each year until 2028, when it would reach the funding level required by that agreement. That included $1.7 billion in additional funds in the Fiscal 2021-2023 budget.

Source: Kris Nordstrom, North Carolina Justice Center

But that budget, passed in November, didn’t include the additional educational funding, even as the state held a roughly $9 billion surplus in its general fund. Judge Lee issued his funding order the same month.

Undecided for 25 years

Melanie Dubis, a partner with North Carolina-based Parker Poe, has represented plaintiffs, including school districts, in the Leandro case for her entire legal career. In an interview, Dubis said she was proud to have been involved with a case of such significance, but frustrated that it had gone on so long without remedy.

“Now is the time,” Dubis said. “I mean that not just from a practical standpoint in terms of the state budget and the economy, but from a legal standpoint, now is the time. The case has run its course, and the issue is ripe for our state supreme court to decide: if not now, then when? Does the court have the authority to enforce its orders or is the judicial branch subservient to the legislature? I would say, if not now, potentially never. If the court cannot enforce this, then we are at the mercy of the legislature and there does not seem to be a legislative fix coming.”

One of the biggest sticking points in the standoff is the question of who gets to decide how public funds are spent.

“Our position is that the legislature decides how to spend taxpayer dollars,” said Pat Ryan, a spokesman for the Republican leader of the state senate, Phil Berger. Ryan told MarketWatch that the WestEd report is “a lobbying advocacy document. We never spoke to WestEd nor did they seek our input at all.”

In December, Berger and Republican House Speaker Tim Moore asked to be allowed to intervene in the case as defendants, after having consistently said that the executive branch, not the legislature, had spoken on behalf of “the state” in the case for years. Ryan called that “a source of frustration” for Republicans in the legislature.

Moore’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment. The governor’s education director didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Asked whether North Carolina adequately funds public education, Ryan said “we would say: yes.” He added, “Republicans in the legislature have long held the idea that money doesn’t buy outcomes. Also, Republicans have been in control of the legislature since 2011, and per-pupil funding has increased by 39% over that period,” a statistic he calls in line with the average increase across the nation.

Controlling the purse

In a November op-ed in the Charlotte Observer, Robb Leandro, one of the original plaintiffs in the dispute, wrote that “our case was never about politics. Neither party is wholly blameless or at fault, and when in power neither party has fixed the problem.” Leandro is now a partner at Parker Poe.

Yearslong battles over funding have been taking place in states both red and blue, including notable cases in Massachusetts, Washington state, Pennsylvania and Kansas.

Still, the Education Law Center’s Sciarra notes that “it’s typically states without broad-based income taxes” that are facing education funding challenges. In 2021, North Carolina reduced income taxes further, cutting the personal income-tax rate to 3.99% from 5.25% over six years, and is in the process of phasing out the corporate income tax altogether.

For Michael Rebell, a professor who litigated a decadeslong education funding lawsuit in New York state, one of the most “fascinating” things about the court challenges around the country is that it’s often Republican states where courts issue the strongest rebukes of the legislative branches, perhaps in part, he said, because funding is so low to begin with in those states.

“There’s a concept of ‘adequacy’ which means that in addition to the fact that kids in poor districts don’t do well, in a state like Kentucky the court determines no one is getting enough,” Rebell said in an interview.

The extent to which Judge Lee was willing to push the legislature in North Carolina is rare, Rebell said: usually all three branches of a state government agree on a path forward.

Still, it isn’t unheard-of for courts to take dramatic steps. In 2016, the Kansas Supreme Court threatened to shut down the state’s public education system rather than allow it to continue operating in a manner at odds with the constitution, which required the legislature to make “suitable provision” for funding.

Litigating as students fail

Kris Nordstrom, a senior policy analyst at the left-leaning North Carolina Justice Center, said the heart of the Leandro standoff now is about “whether or not another two or three generations of students are going to have to wait to get the schools they deserve.”

“There’s a big cost that we as a society incur by not funding this plan, by not allowing so many students to meet their potential,” he said.

Nordstrom, a specialist in public education issues, spent nearly a decade working with the North Carolina general assembly’s nonpartisan Fiscal Research Division. For him, the question of what he calls “what does our state constitution mean if one branch is allowed to pick and choose which parts they want to follow” is a lesser concern than the larger issue of paying to educate all children adequately.

In his December op-ed, Robb Leandro agreed:

“The investment we make in improving education for students in low-wealth counties today will be rewarded in the future with increased tax revenue and reduced spending on social programs,” he wrote, nodding to North Carolina’s strong fiscal position and surplus.

Bickering over who has authority over the case, Leandro said, “does little to help students in failing schools. Instead of wasting valuable time litigating over the court’s authority, the N.C. General Assembly should eliminate the need for a judicial order altogether by uniting to support the plan and committing the financial resources necessary for it to succeed.”