This post was originally published on this site

Even as the government reported the fastest economic growth in nearly 40 years, the air that inflated the economy in 2020 and 2021 is escaping.

The air that cushioned the working class from the COVID pandemic is leaking away. The air that boosted the profits and portfolios of the investing class is deflating. The air that intoxicated the stock market

SPX,

COMP,

the bond market

TMUBMUSD10Y,

the housing market, the crypto market

BTCUSD,

the SPACs, the NFTs and the memes is fizzling away. The air that inflated consumer prices is going, going, gone.

The massive unprecedented stimulus of the recent past has been replaced by massive unprecedented dampening of incomes and wealth. The wailing noise you hear is the sound of belts tightening.

Negative fiscal and monetary policy

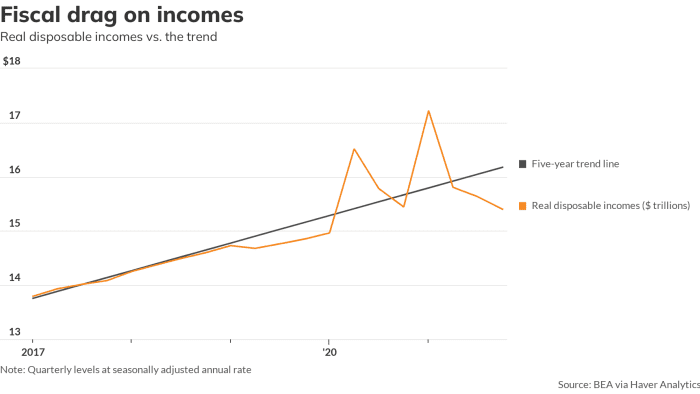

Fiscal policy has already turned sharply negative, tugging down on an economy that it once pushed up. The income support given to workers, businesses, and local governments has been withdrawn. It’s time to stand on your own. After adding more than 5% in first year of the pandemic, fiscal policy will subtract about 2.5% a year from growth over the next two years, says the Hutchins Center’s fiscal impact measure.

And now the Federal Reserve is telling us clearly that the Era of Free Money is over. Fed Chair Jerome Powell just announced last call. The punch bowl isn’t going to be refilled this time. It’s closing time at the Central Bank Saloon.

Breaking news: Powell says Fed is ‘of a mind’ to raise interest rates in March to fight high inflation

The possibility of a hard landing can’t be disregarded.

It’s been so long since the Fed did this. The Fed that most investors know is the one that always props up stock prices whenever it gets a whiff of a bear market. But with inflation running at 7.1% for the past year, the Fed is back in full Paul Volcker mode. At least, that’s what Powell wants us to believe.

Follow the complete inflation story at MarketWatch.

Inflation’s causes

To be clear, much of our inflation problem really just stems from the massive shock to both supply and demand that had little to do with monetary policy, interest rates

FF00,

or money supply. Lots of things cost more now because COVID disrupted all of the fragile global supply chains that modern multinational financial capitalism has strung together to connect cheap labor and raw materials to the markets in the advanced and emerging economies where the people with money live.

Here’s where the inflation came from in 2021

You want a car but you can’t get one because Taiwan can’t make or deliver enough computer chips to satisfy the demand. It’s going to take time to build the capacity and reknit the supply chains, but delayed gratification is a lost art. We’ve become accustomed to getting anything we want at that exact instant we desire it. So we pay whatever it costs to get it now.

“The COVID recession was the first downturn in history that left most people richer than they had been before.”

COVID also twisted the usual spending patterns. With less access to face-to-face services such as travel, entertainment and recreation, people naturally bought more stuff—durable goods—to replace the services they craved but could no longer enjoy.

But a portion of our inflation problem is the classic imbalance of too much money chasing too few goods and services. The COVID recession was the first downturn in history that left most people richer than they had been before. Congress pumped trillions into household and business bank accounts. The Fed pumped trillions into reserve balances, and some of that sloshed into financial markets. And the world of crypto created trillions more out of thin air, the ultimate fiat currency.

Fiscal policy supported the incomes of the working class while the full faith and credit of the Federal Reserve stood behind the portfolios of the investing class. Everyone felt richer and they spent like it.

The “problem” of too much money is being solved, even before the first increase in interest rates.

Real disposable incomes fell at a 5.8% annual pace in the fourth quarter.

MarketWatch

Real incomes falling

Incomes are now dropping like a stone. Most of the support Congress provided last year and the year before has been withdrawn. Real disposable incomes (adjusted for purchasing power) fell at a 5.8% annual pace in the fourth quarter and are on target to fall further in the first quarter as the refundable child tax credit goes away and inflation eats up any wage gains workers manage to get.

Workers managed to save some of the windfall that Congress provided earlier, but they’ll soon run through that. Then hunger and the need to put a roof over their heads will bring millions back into the labor force, resigned to take any job, no matter how unsafe, inhumane or poorly paid. It will give new meaning to the phrase “The Great Resignation.”

And what of the wealth of the investing class? As of early January, it was up about 30% (or a cool $30 trillion) since the depths of the March 2020 selloff. The S&P 500 is down about 10% from its highs. Gradually, financial markets are repricing the value of the Fed put—the now-obsolete assumption that the central bank would keep filling up the punch bowl whenever it looked like the party might end.

If the Fed isn’t going to support asset prices any more, then most assets look a little (or a lot) overvalued. They’ll find a new equilibrium soon enough. But odds are that wealth of the investing class won’t go up another $30 trillion over the next two years.

Where does that leave the economy? Powell says that the economy is strong and that everyone can tolerate the Fed’s anti-inflation medicine. But I think that’s bluster. Underneath the surface, the foundation looks weak.

The question for Powell is this: Who’ll crack first?

Join the debate

Nouriel Roubini: Inflation will hurt both stocks and bonds, so you need to rethink how you’ll hedge risks

Rex Nutting: Why interest rates aren’t really the right tool to control inflation

Stephen Roach: Thankfully, the Fed has decided to stop digging, but it has a lot of work to do before it gets us out of hole we’re in

Lance Roberts: Here are the many reasons why the Federal Reserve won’t raise interest rates as much as expected