This post was originally published on this site

From the coronavirus pandemic shining a light on the wealth gap to ongoing protests over police brutality, the past few years have underscored the persistence of systemic economic and racial inequality in the United States.

But some politicians, pundits and members of the public continue to deny and downplay that inequality, despite ample evidence.

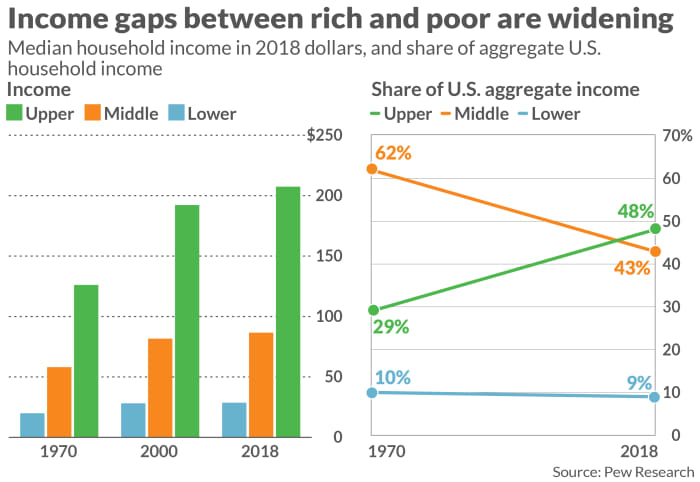

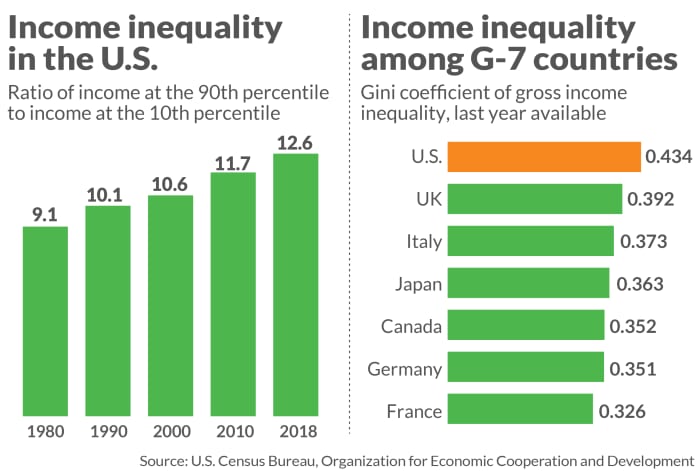

The typical white family today has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family, according to the Federal Reserve. The United States’ wealthiest top 10% owned 76% of the wealth as of 2019, also according to the Fed. And overall inequality has grown in recent decades, with the highest-earning households steadily increasing their share of all U.S. income, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data.

The richest U.S. billionaire holds more wealth than the bottom 40% of the country, and American billionaires’ wealth has risen $2 trillion during the pandemic, says a recent report on taxing “extreme wealth” by the Fight Inequality Alliance, the Institute for Policy Studies, Oxfam and Patriotic Millionaires.

Academics cite a multitude of reasons people choose to ignore, disbelieve or rationalize facts about systemic inequality, which they say is keeping this country from implementing policies that can help chip away at it. Among them are the belief in meritocracy and, in turn, the American dream; political polarization; and continued segregation in where people live, attend school and work — or all of the above.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Sandy Fennell, a 55-year-old white woman in Pennsylvania, calls herself an “ex-conservative” — someone who used to think there was “still some discrimination around, but not much.” Then, she said, she could no longer ignore the history of institutional racism that she began to read about in her 40s. Or the data. Or the disturbing cellphone videos of Black people being shot and killed by police.

After her own awakening, Fennell said, she is surrounded by people who continue to engage in the kind of inequality denial that in some cases is louder than ever.

Take, for example, the controversy in schools over the teaching of critical race theory, the higher-education study of how race has shaped public policy that has morphed into a catch-all term for discussing any kind of racial inequality. In Florida, one of more than 30 states where lawmakers have considered legislation related to critical race theory, one proposed bill would also prohibit “private businesses from making white people feel ‘discomfort’ when training employees about discrimination,” according to the Associated Press.

“CRT forces people to look at themselves, asking them to admit a painful truth about themselves,” Fennell said. “People are going to resist that.”

Fennell said she grew up a Catholic, with “rosy ideas about racial tolerance that came from pop culture: ‘Sesame Street,’ Mr. Rogers, Three Dog Night singing ‘Black and White.’” Her Catholicism shaped her anti-abortion views, so she aligned with conservatives. She believed racial discrimination was largely over, and that police brutality was “greatly exaggerated.”

Sandy Fennell of Pennsylvania says her views about inequality have evolved over time.

Courtesy of Sandy Fennell

In her 40s, she finally learned about redlining, the practice of denying loans and other financial services to people of color; the Tulsa Race Massacre; and the fact that Black veterans of World War II were denied the same benefits the G.I. Bill conferred to white veterans. Those revelations, combined with what she called racism toward former President Barack Obama by leaders of the Catholic Church and some of her fellow congregants, began to change her views.

“You let yourself be persuaded by people who make the argument that Black people are [not working hard],” Fennell said. But “in Pittsburgh, where I’m from, Black people [for a time] couldn’t get jobs in the steel mills,” she added.

Now, she said, “it’s crucial that children learn what happened after slavery was over.”

Not all awakenings to systemic injustice have staying power.

In May 2020, a white police officer’s murder of a Black man, George Floyd, was caught on cellphone video and inspired people to head to the streets to protest police brutality and racism. Individuals, politicians and corporations proclaimed “Black lives matter” and pledged billions of dollars toward righting historical wrongs.

But “most of that awakening is short-lived and temporary,” said Michael Kraus, an associate professor of organizational behavior at Yale University and social psychologist who studies inequality. “It’s something that happens in the moment when you’re forced to contend with the magnitude of racial inequality.”

Now it appears there’s not only a reversion in attitude, but a backlash against social-justice movements, Kraus said.

White Americans’ support for the Black Lives Matter movement peaked at 43% in June 2020, and had fallen to 34% as of this January, according to data from the online polling company Civiqs. In June 2020, 35% of white Americans opposed Black Lives Matter. Today, that number stands at 51%.

Why people still believe the U.S. is a meritocracy

The “painful truth” Fennell mentions — that merit may not always be the reason someone is successful — has been the subject of a lot of research.

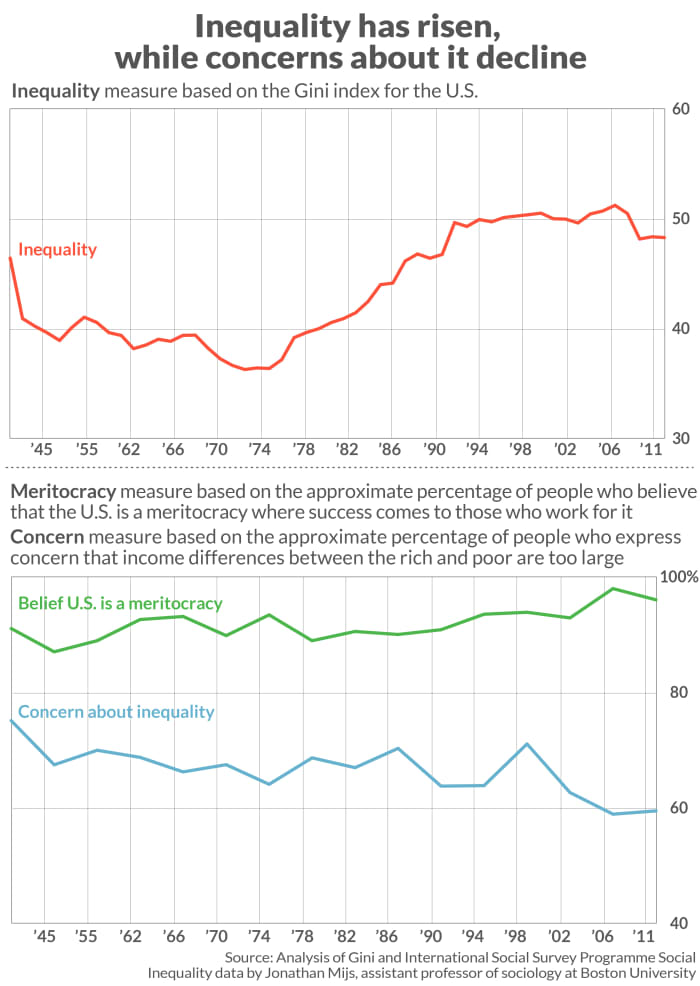

Between the 1980s and 2010, a period during which the gap between the wealthy and the rest of the country widened, Americans actually came to believe that their society functioned more like a meritocracy, according to research (which is the source of the graphic below) from Jonathan Mijs, an assistant professor of sociology at Boston University.

Part of that discrepancy between public opinion and reality can be explained by the prominence of the American dream, or the idea that if you work hard in school and at your job you can achieve success, Mijs said. Americans’ strong belief in that idea means that wealth can often come across as deserved, he said.

“The question then becomes: How could this belief in meritocracy be sustained in the context of growing inequalities?” Mijs said.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

One reason is a tendency by some people to deny that their class affords them certain advantages, the subject of a paper co-authored by Brian Lowery, a professor of psychology at Stanford University.

Lowery’s research showed that white people, like most people, want to be seen as good and deserving of what they have — so they use “cloaking strategies” to deal with the discomfort they feel about their privilege. That includes highlighting the hardships they experience and how hard they have worked.

“People want to say they have what they have because of hard work,” he said. “But so much is predicated on what your parents have.”

The power of family wealth to determine outcomes is why inequality in this country is so intertwined with race. Kraus, of Yale, points out that “any past racism gets carried over in wealth. It goes all the way back to chattel slavery, all the way up to the G.I. Bill, redlining, college debt — any way that you can accrue wealth,” he said. “All that will show up in whether Black families have savings.”

A study published in 2019 that Kraus co-wrote found that Americans, even if they acknowledge the existence of inequality, tend to overestimate the progress toward its elimination. And when it comes to estimating the nation’s progress in closing the racial wealth gap, most people think Black people have a higher share of wages, income and benefits than they actually do.

“In general, all Americans are overestimating the amount of equality,” Kraus said. “Black families are a magnitude more accurate. It’s just that everybody’s off.”

Segregation means people ‘don’t see growing economic inequality’

Mijs points to increased socioeconomic segregation in American society during the same period that inequality has grown. K-12 schools are more divided along racial and economic lines today than they were in previous decades; colleges are also often segregated along race and class lines; and workers with different educational backgrounds are less likely to mix at the water cooler.

What’s more, Americans are also likely to marry people of similar class backgrounds, reproducing that stratification.

“If you’re in a context where most of your friends, people you work with, are similarly educated, have similar levels of income — then you don’t see growing economic inequality,” Mijs said. “If you all share the same advantages or you share the same disadvantages … you fail to notice their importance.”

The COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed the gaps between rich and poor and white and non-white Americans, provided Mijs with an opportunity to test whether pointing out the inequality present in society could change people’s minds.

“‘There definitely is potential for better campaigning, better information. But it’s going to be really, really hard to break through partisan polarization when it concerns really strong partisans that are completely entrenched.’”

He and fellow researchers showed a representative sample of Americans information about the pandemic, including the level of unemployment and its disproportionate impact on low- and middle-income families, as well as on Black and Latino communities. They also showed the participants information about how a small group of billionaires saw their wealth grow. The team exposed a control group of participants to information on a different topic.

They found that among those who learned about the disparate impacts of the pandemic, the gap in the view of inequality between moderate Democrats and moderate Republicans narrowed and almost disappeared.

“But the position of really strong partisans, particularly on the Republican side, entrenches,” Mijs said. “They get less concerned about inequality than they were before.” These participants are so invested in their political opinion that they don’t respond to factual information, and may even respond negatively to it, he said.

Providing people with information about racial inequality has similarly divergent impacts, research from economists at Harvard University and Boston University suggests. The group showed a sample of adults and teenagers information about subjects like the differences in the likelihood of Black and white children born in the U.S. to become rich, and how the Black-white earnings gap has evolved over time.

The researchers found that members of both races generally believed in this information, said Matteo Ferroni, a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University and one of the authors of the paper. “We are able to close the gap on the perception of inequality today,” he said. But seeing that data didn’t change the participants’ perspectives on the causes of that inequality, Ferroni added.

Earlier research by some of the authors indicates that policy preferences for addressing inequality are tied very closely to what they view as the causes of that inequality. For example, if you believe that poverty is the result of bad luck or bad circumstances, you’re more likely to support policies that redistribute resources. On the other hand, the more you believe in the idea that a poor child can become rich when they grow up, the less likely you are to favor redistributive policies.

The researchers tried providing a different type of information to participants to see if it would change their views on the causes of racial inequality. They used a more narrative-based approach, telling the participants about things like redlining. “We were able to move the perceived causes,” Ferroni said. “They actually also shift their policy preference.”

But that wasn’t true of all the participants. While this approach worked to persuade Black respondents and white Democrats, it had no impact on white Republicans.

Politics, polarization and the information wars

The polarized dynamic in the way different groups view information, as indicated in both Ferroni’s and Mijs’ studies, creates challenges for addressing inequality, Mijs said.

“There definitely is potential for better campaigning, better information,” Mijs said. “But it’s going to be really, really hard to break through partisan polarization when it concerns really strong partisans that are completely entrenched.”

Though that polarization exists in other countries, it’s an area “where the U.S. really stands out,” he said. It’s one of the few nations with such an ingrained two-party system that often doesn’t yield well to compromise. “The problem is worse and the solution is further away,” Mijs said.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Matthew Hawn, a white high school teacher in Kingsport, Tenn., was surprised his lessons about white privilege sparked such a strong backlash last year. Though Hawn knew that some of the topics he broached with students in his contemporary issues class often had sides that aligned with certain political parties, he’d managed to discuss these subjects with his students for years without receiving complaints.

Now Hawn is fighting to get his job back after being fired over the white-privilege content. “There is an external political environment — it’s so divided, everything is political,” Hawn said of why the lessons caused such controversy now. “I thought, ‘I kept that out of the classroom for a decade; that’s not going to creep in here.’”

While he found the pushback “shocking,” particularly given that he lives in a relatively small, close-knit community, Hawn can empathize with the mental adjustments students go through when presented with some of the ideas that come up in his class.

Tennessee high school teacher Matthew Hawn is fighting to get his job back after his lessons about white privilege sparked a strong backlash.

Courtesy of Matthew Hawn

“I grew up believing that we all had the same opportunities, and if you worked hard enough then you could overcome obstacles,” he said. It wasn’t until he started studying history in college, and, in particular, encountered a professor working on taxation issues, that he started to think differently. Tennessee has no income tax, but it has a sales tax that’s higher than in some surrounding states — a fact he never really thought about, except for when he would drive over to Virginia to buy goods at a cheaper price than what he would find at home.

But through a discussion about a proposal to get rid of the sales tax on food, medicine and clothing — items low-income people were spending the bulk of their funds on — up to a certain dollar amount Hawn started to think more critically about the idea of funding the government through sales tax alone.

“By paying the same tax on goods, it’s really unfair to those people,” Hawn said. “I had never heard that before.”

As a teacher, Hawn would present the information and watch as his students digested it. He taught in a school where at least 40% of the students come from low-income families. “It’s hard to think about you having privilege when you don’t know where your next meal is coming from, or you’re struggling to pay the bills, or you have to work because you have to help the family maintain the household,” he said.

On other topics such as the #MeToo movement or the minimum wage, students may be hearing an alternative perspective for the first time in his class, a process that can be almost “shocking” to them, Hawn said. He works to probe their sources of information and help them discover reliable sources of their own that might change the way they think about an issue. For example, after a student repeated inaccurate claims he found on social media about undocumented immigrants benefiting from a variety of government resources without paying taxes, the class worked on an in-depth assignment researching those claims.

Hawn watched the student assess the findings and think, “Well, that doesn’t really line up with what I originally thought,” he said.

“‘It’s hard to compromise when we can’t even agree on what reality is. It makes it almost impossible to talk about what the solutions are.’”

Taking the time to let people discover reliable sources of new information may help open their eyes to inequality, but it’s not something that can be done at scale. Rebecca Ponce de Leon, a Ph.D. candidate at Duke University, co-wrote a 2020 study on the political and ideological roots of skepticism about inequality. She and her fellow researchers found that Republicans deny the harmful effects of inequality more than Democrats do.

That’s because Republicans tend to dislike many policy solutions to inequality, she said. When she and her colleagues showed participants separate studies about the harmful effects of economic inequality, they found that “Republicans were more likely to deny that findings were reliable and trustworthy when the solution was wealth redistribution or reparations.”

Their research also found that people higher in social-dominance orientation (SDO) rejected these findings regardless of the proposed solution. SDO, a term coined in the 1960s, is a tendency to accept or prefer social hierarchies that sustain inequality.

Ponce de Leon says that “typically, conservatives are higher in SDO and liberals are lower in SDO.” That kind of thinking can manifest in overlooking structural racism and blaming individuals for their circumstances, she said.

“The crazy thing is in the last several years, it really feels like based on your political affiliation, you’re operating on different facts,” Ponce de Leon added. “It’s hard to compromise when we can’t even agree on what reality is. It makes it almost impossible to talk about what the solutions are.”

Nancy DiTomaso, a professor of business and management at Rutgers Business School, said that is by design. As issues of racism and inequality persist and politicians and others offer possible solutions, she said, there has been an effort “orchestrated by right-wing billionaires who have put together organizations to try to change the conversation.” Those include conservative-leaning think tanks and other entities that try to influence politics, higher education, the judiciary and more.

“To some extent, the rush among Republican legislators to try to prevent people from talking about racial inequality is another manifestation [of the] wish to keep things hidden … under wraps,” she added.

Possible solutions to inequality denial

For DiTomaso’s 2013 book, “The American Non-Dilemma: Racial Inequality without Racism,” she spoke with nearly 250 white people in New Jersey, Ohio and Tennessee, and found that many of them were unaware or willfully ignorant that they were benefiting from their privilege.

They “had various ways in which they used the help of friends, family and acquaintances to help them get into jobs,” she told MarketWatch. “It’s not that they didn’t discriminate against Blacks, but they also didn’t need to. They worked with whites helping other whites.”

She found that most of the white people she interviewed lived segregated lives that extended to the workplace, except for those who lived on the coasts. “Almost no one had encounters with Black people, except when they went to college,” she said.

DiTomaso said those she spoke with saw solutions to any existing racial inequality as providing equal opportunity. “Yet they spent their lives seeking unequal opportunity,” she said. In her book she calls it “opportunity hoarding,” a concept scholars have used to describe control of resources that contributes to inequality.

“They didn’t think about the fact that [because they got] in the door, others would not,” she added.

Her take on possible solutions, at least in the workplace: Instead of putting people on the defensive by trying to change people’s individual biases against other people, focus on highlighting the fact that current systems as a whole, including hiring recommendations, for the most part work in favor of white men.

“[White people] should be willing to help not just [their] children, but other people’s children,” she said. That’s where affirmative action and other programs that widen talent pipelines come in, she added.

“‘People want to make peace with the status quo. They want to accommodate to the social, economic and political realities around them so that they’re not pushing against those forces.’”

As for politics and its ties to continued inequality denial — which holds back policy solutions — getting people to come around requires time and patience.

In Pennsylvania, Fennell has gotten involved with Voice of Westmoreland, a group that does deep canvassing of voters in the rural and mostly conservative county.

Deep canvassing is not “just about persuasion, arguing or telling people why they’re wrong,” said Sarah Spiegel, a volunteer for the organization. “It’s about active listening, focusing on empathy and getting people to move through their own emotional struggles around issues.”

In the 2020 election, she said the group made more than 2,000 deep-canvassing calls and saw that 22% of the completed conversations moved people toward voting for now President Joe Biden. Some of that had to do with the county residents’ concerns about inequities in healthcare, Spiegel said.

A ‘complicated web of justifications’ for inequality

Where someone falls on the socioeconomic spectrum doesn’t necessarily indicate their views on inequality. In fact, some who are disadvantaged by an unfair economic system may still believe it’s justified. This phenomenon is known as system justification theory — a term that Mahzarin Banaji, a professor of psychology at Harvard University, and John Jost, the co-director of the Center for Social and Political Behavior at New York University, coined in a 1994 article.

How does Jost define it? In part: “People want to make peace with the status quo. They want to accommodate to the social, economic and political realities around them so that they’re not pushing against those forces — because they’re very powerful forces,” he said.

People who score higher on measures of system justification tend to perceive less inequality than those who score lower, research indicates.

“It’s harder for them to also acknowledge that we live in a world that is very unjust — because living in a world that’s very unjust, very unfair, gets us in a place where things are out of control,” said Daniela Goya-Tocchetto, a Ph.D. candidate in management and organizations at Duke University who has studied this relationship. “It creates a lot of dissonance and it’s not comfortable to walk around thinking that everything is unfair and everything is unjust.”

The justifications people make for the world around them can come in the form of broad ideologies, like the idea that wealth is the result of hard work and intelligence. In other cases, the justification may relate more to someone’s personal decisions, Jost said — for example, managers coming up with a rationale for why they pay workers a certain wage, or households making peace with the often relatively low wages they pay to people who perform care or domestic work.

“We’re all caught in a really complicated web of justifications for everything we’re doing,” Jost said.

Part of our urge to justify the unequal economic system around us is that the economy has changed dramatically over the past few decades into one where workers have become even more productive, while those at the top of the economic ladder have continued to capture more wealth. At the same time, our psychological approach to these issues — for example, the pervasive belief in meritocracy — hasn’t changed much during the same period, Jost said.

One optimistic takeaway from the idea of system justification is that it indicates that if the system ever changes, people will likely eventually adjust their psychological approach to mirror it, Jost said.

“People adapt themselves to the new status quo and then they come with explanations and justifications for why that system works,” he said. “There are countries, for instance, in Northern Europe, where they have much higher levels of economic equality — and people there find it perfectly justified and fair and reasonable.”