This post was originally published on this site

Food prices are going up. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, consumers are paying about 6.5% more for a grocery food basket and for fast food and restaurant meals compared to a year ago. This is not substantially different from the 7% increase in the average prices paid by consumers for all commodities.

Despite the increase in retail prices for food, several farm groups and some commentators are complaining that their members are not seeing any increase in the prices of their crops and livestock. They argue that stagnant “farm gate” prices (prices at the farm, not counting transport et al), combined with surges in fuel and fertilizer costs over the past five months are putting their operations at risk.

A frequent claim is also that the four largest beef meatpacking companies (Cargill, Tyson Foods

TSN,

JBS SA

JBSS3,

and National Beef Packing) have been using their buying power aggressively to depress farm gate prices while obtaining larger marketing margins and much larger profits through higher prices.

While the Biden administration and some farm organizations representing cattle and other livestock producers have been vocal in airing their concerns, let’s check the facts regarding farm incomes, farm gate prices, wholesale prices, and retail prices for the agricultural sector as a whole, and for beef and pork producers.

The real winners have been retailers’ margins.

The most recent (December 2021) USDA forecasts for national net farm income, total farm revenues from sales of crops and livestock, and government subsidies in 2021 tell a clear story.

The USDA estimates that total farm revenues from all sources of farm income have increased by 14.7% in 2021, despite direct government subsidies falling by about $18 billion to a little over half their 2020 levels as pandemic-related subsidies came to an end. Farm revenues in 2021 from crop and livestock sales are expected to increase by 17.8%, or about $65 billion. Prices for commodities such as wheat, corn and soybeans have been consistently higher than before COVID-19.

As a result, even though fertilizer and energy costs have increased, net farm income ($116.8 billion ) for the agriculture sector will be 23% higher in 2021 than in 2020, and (adjusting for inflation) much higher than annual farm incomes in 2013-2020.

These numbers do not support the story that farm gate prices and revenues have been stable or even declining. Only fresh vegetables and milk have had lower or relatively stable farm gate and wholesale prices.

“The largely untold story for both beef and, especially, pork is what happened to the gap between prices in the grocery store and the wholesale prices paid to meat packers..”

So what are the facts regarding meatpacking companies?

Unequivocally, between December 2020 and December 2021, retail prices had increased sharply for beef (by 18.6%) and pork (by 15.1%). What happened to farm gate and wholesale prices is more complicated.

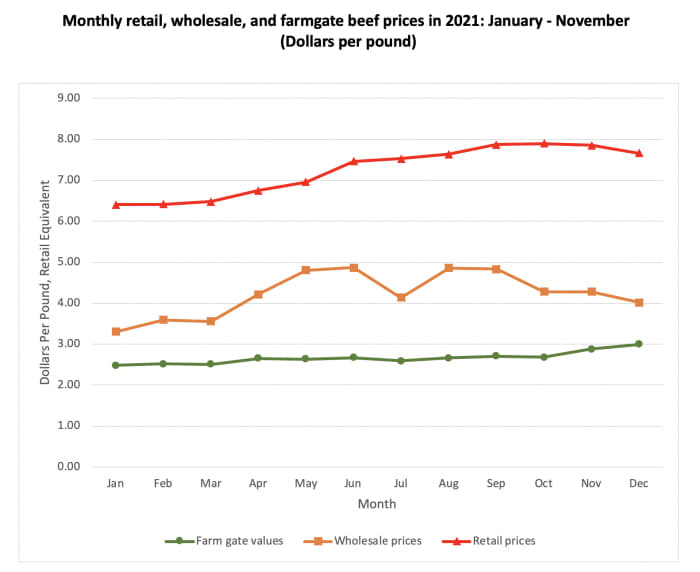

According to USDA, in 2021, prices paid to farmers for their beef increased from an average of $2.48 in January to $3.00 in December — a one-year jump of 20% — per pound of retail equivalent product, proportionately more than the BLS estimate of the increase in retail prices. Much of the increase occurred in November and December. Wholesale prices also increased in 2021, surging more rapidly than farm gate values between April and June, then jumping around until September, after which they declined substantially.

U.S. Department of Agriculture

The gap between wholesale prices (which include feedlot expenses as well as packing plant costs) and farm gate values was $0.82 per pound in January and $1.02 in December, while increasing to $2.20 in June and August.

Part of the differences between farm gate and wholesale prices for beef were due to higher corn prices affecting feedlot costs, not because of the meat processors exercising their buying power. Packers had to contend with higher labor costs because of sharp increases in wages and changes in production practices.

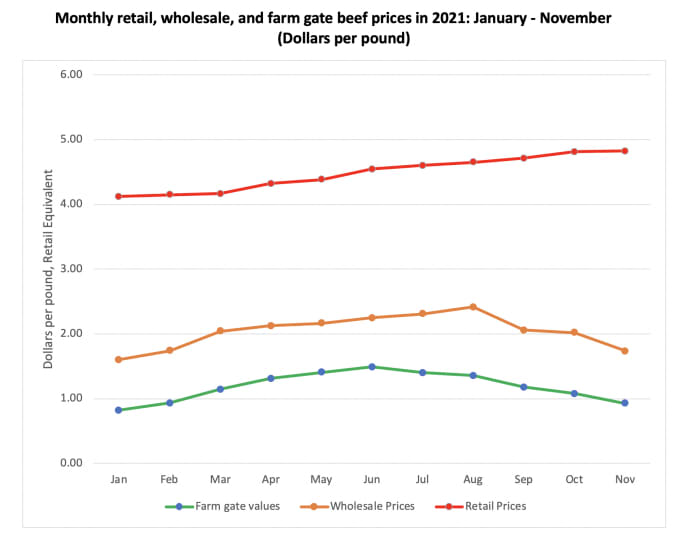

The largely untold story for both beef and, especially, pork is what happened to the gap between prices in the grocery store and the wholesale prices paid to meat packers. Retail prices went up steadily for both beef and pork, until stabilizing and very modestly declining in the last quarter of 2021. In contrast, wholesale prices for beef and pork dropped sharply in late summer through December. The gap between retail and wholesale prices for both beef and pork reached near-record levels in November and December 2021.

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Much of the substantial increase in retail margins can be linked to higher trucking and other transportation costs, increased wages for workers, and the impact of other short-term supply chain bottlenecks.

For both beef and pork, the surge in higher retail prices is a story about a surge in retailer margins, and much less to do with wholesale-farm gate margins. Interestingly, when farm gate values for pork declined between September and November 2021, wholesale prices also fell by almost exactly the same amount. For beef, wholesale prices dropped as farm gate prices increased.

There is thus little evidence to support the notion that higher consumer prices for meat have been driven by an exercise of buying power by large meat-packing companies to depress farm gate prices. Nor have farmers received lower prices for their beef. Finally, while agricultural production involves hundreds of commodities, in 2021 the evidence is that the farm sector overall had a very good year.

Vincent H. Smith is director of agricultural policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C. He is also a professor of economics in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics at Montana State University in Bozeman.