This post was originally published on this site

Consumer prices rose 7% between December 2020 and December 2021, the third month in a row that this year-to-year inflation rate exceeded 6%. This December figure is the largest 12-month increase in 40 years. A central concern now is whether inflation will be transitory or, instead, we are entering a persistently high-inflation period, like what occurred in the 1970s.

The proximate causes of current inflation include supply-chain disruptions, labor shortages, and pent-up consumer spending. But another important source of ongoing high inflation is an expectation of high inflation among households and businesses. How does the expectation of high inflation become self-fulfilling, and what proxies do we have to reflect this inherently unobservable but very important economic variable?

Get the complete story on inflation

If people expected the 2021 inflation rate to continue for the foreseeable future, a 7% rise in prices would become “built in” as future prices are set and as wage and salary contracts are negotiated.

The Facts:

One source of inflation is when spending by people and companies strains the economy’s capacity for providing goods and services. Strains on the economy’s productive capacity can arise because of an increase in demand, constrictions to supply, or some combination of these two factors. Currently in the United States and other developed countries it is the combination of high demand and constrained supply that is feeding inflationary pressures.

Demand in the United States was supported through the first year-and-a-half of the pandemic by government support programs. Cash payments to individuals and families under the CARES act of March 2020, the CARES Supplemental Appropriations Act of December 2020 and the American Rescue Plan of March 2021 contributed to sharp increases in personal disposable income.

Spending may also have been boosted by low interest rates, which have increased the value of stocks, houses and other assets. Supply has been constrained because of a 2 percentage point drop in the share of the population participating in the labor force (either working or looking for a job).

Inflation expectations can sometimes become self-fulfilling. While some prices can change quickly, others are adjusted only infrequently; producers of these goods and services will naturally set their prices based on likely future costs and expectations of what the market will bear in the coming months. Similarly, labor contracts are not renegotiated frequently but instead negotiations set wages or salaries for one or more years at a time.

It therefore matters a great deal how inflation expectations are formed. If people expected the 2021 inflation rate to continue for the foreseeable future, a 7% rise in prices would become “built in” as future prices are set and as wage and salary contracts are negotiated. This would cause inflation to persist even when the economy is no longer “overheating.”

Rising inflation expectations are largely to blame for the persistence of the inflation of the 1970s, which remained elevated well after the booms of the late 1960s early 1970s had run their course.

“Anchored” expectations reduce the risk of persistently high inflation. If people believed inflation would return to its pre-COVID rates once spending cooled and supply-chain issues were resolved, they would assume a slower pace of price increases when deciding on what prices and wages to set today that will prevail in the future.

If firms and workers thought the Fed would manage to bring inflation down from 7% to 4%, for example, they would build correspondingly smaller price increases into their pricing- and wage-setting decisions. With expectations “anchored” in this way, temporary increases in inflation would not become self-fulfilling and inflation would fall more quickly as demand cooled and supply-chain issues were resolved.

The central bank’s commitment to price stability can help anchor inflation. The Federal Reserve’s mandate, as stated in the Federal Reserve Act, is to pursue “maximum employment and stable prices.” Until relatively recently, however, these objectives were not spelled out explicitly; nor was there clarity with regard which would take precedence.

But beginning in the late 1980s then-Fed chair Alan Greenspan made it increasingly clear that the Fed would prioritize price stability; and in 2012 the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced an explicit target inflation rate. These changes are credited with anchoring inflation expectations and reducing inflation persistence.

The Fed’s recent change in its monetary-policy strategy, specifically the adoption of average inflation targeting, in which inflation is allowed to exceed 2% “for some time” and an increased emphasis on the employment objective, has raised questions about the strength of the Fed’s commitment to price stability. The Fed’s credibility may therefore hinge on its handling of the current inflation surge.

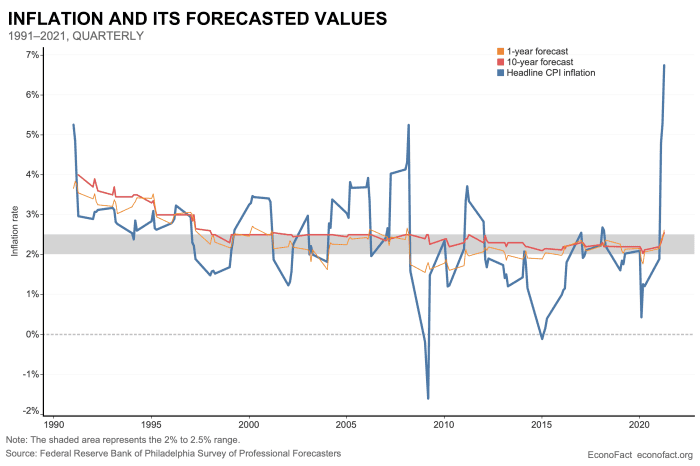

This graphic shows that inflation expectations have been relatively well-anchored even as actual inflation has fluctuated.

Econofact

Indicators of expected inflation suggest concern but not panic. Surveys are one source of expectations indicators. One of the most closely watched is the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) conducted by Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, which solicits the respondents’ forecasts of inflation over one- and 10-year horizons. The median SPF forecasts are presented in the chart. The one-year forecasts are for the year following the date indicated on the horizontal axis (e.g. the data point for the first quarter of 2010 is the forecast for average inflation from the second quarter of 2010 through the first quarter of 2011) and the 10-year forecasts are defined analogously as corresponding average rate over the 10 years following the date indicated on the axis. Also shown is the percentage change over the previous four quarters in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The forecasts’ quiescence is striking; once perceptions of the Fed’s commitment to price stability solidified in the late 1990s, the one-year-ahead SPF forecasts have for the most part remained in the 2% to 2.5% range, in spite of large fluctuations in actual inflation. The 10-year-ahead forecasts have been even more stable, suggesting firmly anchored long-term expectations.

Ironically, the very stability of expectations has made it hard to discern in the past 20 years’ experience any effects on inflation they might have had. The chart shows that the 2021 inflation spike has had only modest effects on the SPF forecasts so far, as both were 2.6% at year-end.

Although these indicators are reassuring, they are not cause for complacency. For one thing, the forecasts do not incorporate the most recent inflation data, and consequently they are likely to be higher when the next survey is conducted. Another gauge of inflation expectations is a survey of individuals who are not professional economists conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan. In the survey conducted in November 2021 respondents expected 5% inflation rate over the coming year.

A third way to capture inflation expectations is to analyze financial-market data. For example, a five-year-ahead expectations indicator based on the difference between nominal and inflation-indexed bonds is 1.3 percentage points higher now than before the pandemic. Of these three, the SPF forecasts have a record of being most reliable. The Michigan survey’s flaws have been thoroughly documented and it has systematically over-predicted actual inflation by 0.8 percentage points during the period from 1999 through 2019. The bond yield-based indicator is highly volatile and heavily influenced by financial-market conditions.

What this Means:

The 2021 inflation surge has created a great deal of discomfort as many people saw their purchasing power decline as price rises outpaced increases in their income. A longer-lasting period of high inflation could be even more damaging because it would create distortions and disproportionately harm low-income families, who typically hold a larger share of their assets in the form of cash and checking accounts as well as those living on fixed incomes or whose wage or salary increases do not keep pace with price inflation.

One immediate concern is that high inflation will compel the Fed to respond with interest rate hikes that will slow the economy. If expectations remained anchored, only modest interest-rate increases would be required—just enough to bring spending back into balance with the economy’s productive capacity. If, on the other hand, expectations of high inflation were to become embedded, a more aggressive response and significantly larger rate hikes would be required to bring inflation back down, and a recession would almost certainly ensue.

The members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) were anticipating, as of Dec. 15, only a small interest rate increase in 2022, to an annual average of 0.9%, but since then many are expecting a more aggressive response. This more proactive policy response, intended to keep inflation expectations in check, would be especially warranted if inflation expectations begin to rise.

Kenneth Kuttner is a professor of economics at Williams College, with expertise in macroeconomics, monetary policy, macroprudential policy, and the Japanese economy.

This commentary was originally published by Econofact.org—Thinking Can Make It So: The Important Role of Inflation Expectations

More views on inflation

Jason Furman: Why did almost no one see inflation coming?

Rex Nutting: Why interest rates aren’t really the right tool to control inflation

Giovanni Peri: U.S. labor shortages are tied to low immigration in past two years