This post was originally published on this site

Insatiable demand for goods by American consumers heading into the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic is leading to a scenario in which supply-chain bottlenecks may “never” let up, absent major infrastructure improvements at the U.S.’s two busiest ports, based on an analysis by RBC Capital Markets.

In a report released Thursday, Michael Tran, RBC’s head of digital intelligence strategy, and others concluded that “the supply chain stretching from Asia to California is simply not constructed to handle the current level of consumer demand for goods,” and that overwhelming demand “was the crux of the problem.”

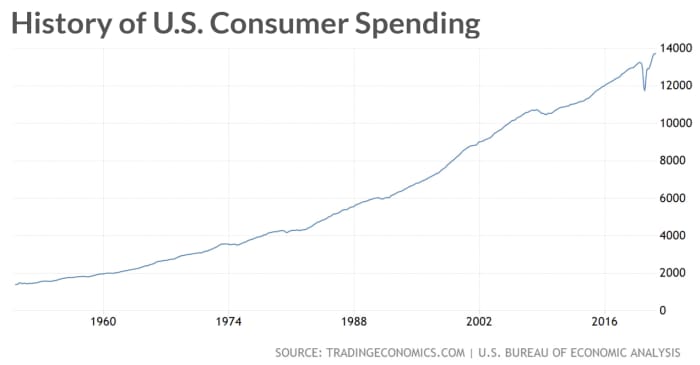

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Tradingeconomics.com

“If demand for goods remains elevated in perpetuity, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach will never fully clear the logistical hurdles required to untangle the supply chain,” and “the supply chain will never normalize, barring significant infrastructure investments,” they wrote. The Port of Los Angeles is the nation’s No. 1 container port, followed by the Port of Long Beach, the second-busiest — accounting for almost 40% of the country’s imported goods as of November.

The findings are significant because they would imply that the highest U.S. inflation rate in almost 40 years could run for much longer and may not ease up even if COVID-19 cases fall off. By focusing on consumer demand, RBC raises the notion of a more permanent dilemma that isn’t yet being factored into the thinking of financial markets or Federal Reserve policy makers, who expect their preferred inflation gauge, the personal-consumption expenditures price index, to drift back toward 2% by 2024 and in the longer run.

On Thursday, Treasury yields remained unchanged or slightly lower, with the 10-year rate

TMUBMUSD10Y,

at 1.7% even after Federal Reserve Gov. Lael Brainard testified that curbing inflation will be the central bank’s most important task for the foreseeable future.

Read: Lael Brainard Says Inflation Is ‘Too High.’ The Fed Will Work to Bring It Down.

Fixings traders are pricing in annual headline consumer-price index gains that gradually fall off this year — coming in at 7.2% for January and staying around 7% until March, before dropping to 3.2% at year-end. Meanwhile, 5- year and 10-year breakevens, which reflect the outlook for inflation, hovered around 2.8% and 2.5%, respectively, as of Wednesday.

“This bond market is not priced for a sustained inflation run, that’s for sure,” said David Petrosinelli, a senior trader at InspereX in New York. If the Federal Reserve can’t arrest inflation with three interest rate hikes through June, policy makers might need to deliver a series of 50-basis-point hikes starting in the third quarter that begins to push the fed-funds rate target above 3%, from what would then be 0.75% to 1%, he said via phone. The target is currently between zero and 0.25%.

First, though, traders would start to aggressively sell off Treasurys during the summer, pushing short- and long-end yields higher by 100 basis points or more over a short period, Petrosinelli said via phone. It’s a scenario that can “easily” come to fruition, considering that rising wages are another “sticky” factor behind high inflation — on top of consumer demand, he said.

The snarled international supply chain has led to long waits for everything from furniture and appliances to new and used autos, grocery items, and semiconductor chips. Some of the logistical challenges are boiled down in the report by RBC, which uses geospatial intelligence to track activity at the world’s 22 largest ports.

| Turnaround time at Los Angeles, Long Beach ports | 7.5 days |

| Amount of time that chassis used by truck drivers to transport containers are held up at port terminals | Up to 9 days |

| Current U.S. truck driver shortage | 85,000 operators |

Read: How stock-market investors can make sense of supply-chain chaos

RBC’s math suggests that U.S. consumer spending would need to be curbed by 15% over 10 months to “untangle the congestion” and put the PCE price gauge “back on the long-term trend line.” Spending on consumer goods, however, is roughly about 20% higher than it was before the pandemic, according to the report.

“Given the strength of the average U.S. household balance sheet, it is difficult to see near-term reprieve unless the consumer shifts significantly and cannibalizes goods spending with services,” RBC’s Tran and the other analysts wrote.

Further aggravating the situation is China’s zero-tolerance policy on COVID-19. It’s led to partial, intermittent lockdowns of the industrial hub of Ningbo; left 200 pilots in quarantine last week after two pilots tested positive in the Yangtze region; and led to the suspension of regional operations for 20 companies over the holidays, which impacted the manufacturing of batteries, textiles, pharmaceuticals and personal protective equipment, according to RBC.

While RBC’s view about the prospect of a never-ending backlog of goods isn’t yet a consensus, others, such as Siemens Energy

ENR,

CEO Christian Bruch, have expressed similar concerns that supply-chain woes are probably here to stay.