This post was originally published on this site

In 2015, the Department of Justice released a report on the causes of the shooting death, a year earlier, of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

Ferguson was “a community where local authorities consistently approached law enforcement not as a means for protecting public safety, but as a way to generate revenue,” then-attorney general Eric Holder wrote.

The report also found that revenue raising was racially biased and had “not only severely undermined the public trust, eroded police legitimacy, and made local residents less safe — but created an intensely charged atmosphere where people feel under assault and under siege by those charged to serve and protect them.”

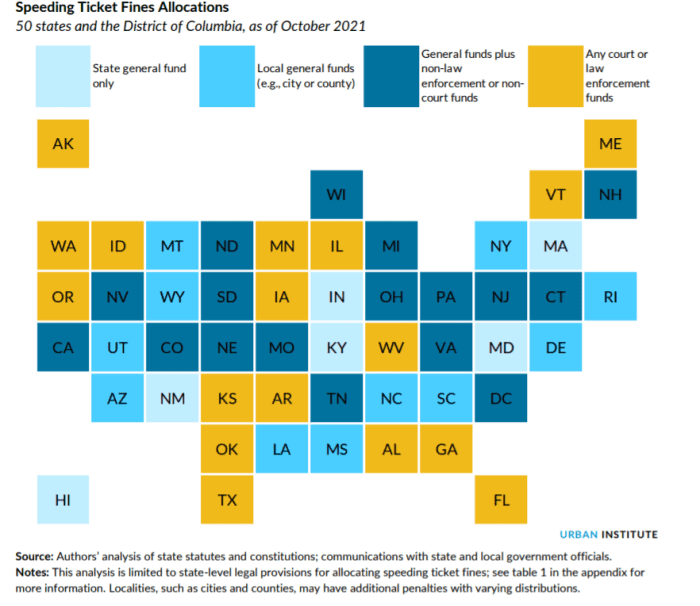

But years later, the practice remains widespread — so much so that in at least 43 states, some portion of speeding ticket revenue goes to a court or law enforcement fund, suggesting the potential for conflicts of interest like in Ferguson, according to a new paper.

The Washington-based Tax Policy Center’s new paper, Following the Money on Fines and Fees, looks at what the authors call “the misaligned fiscal incentives in speeding tickets.” The paper’s contribution to the issue, according to co-author Arvind Boddupalli, is novel in that it matches revenues from fine and fees to how they are allocated, thereby drawing a money trail of potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tax Policy Center analysis of Census Bureau data

The paper also finds that many states use speeding ticket revenue to fund general government services unrelated to the justice system. That’s a gray area, Boddupalli told MarketWatch.

“It’s not conclusively better to send the money to a general fund,” Boddupalli said. “Revenue-motivated policing and sentencing, in and of itself, can be pretty problematic and especially inequitable. There is a lot that can be problematic here.”

Earlier coverage: When fines and fees ruin lives

“Revenue-motivated policing” doesn’t have to end the way things did in Ferguson for it still to have a devastating impact on peoples’ lives. The practice disproportionately targets Black Americans, a raft of earlier research has shown, and it can trap people in cycles of debt, bankruptcy, and a history with the justice system, which can make getting a job or a fresh start much harder.

What’s more, by creating such incentives for law enforcement, it can set up a situation where the financial health of a community is better if people are fined more for breaking the law. But that also often leads to lower public trust in the justice system and a loss of legitimacy — not to mention lower rates of solving crimes, Boddupalli said.

He hopes that his paper, co-authored with Livia Mucciolo, leads to more research focused on tracking the allocations from other types of revenues.