This post was originally published on this site

Will international stocks ever again outperform the U.S. market? It’s worth asking given non-U.S. stocks’ disappointing results in 2021 — the fourth year in a row in which they lagged their U.S. counterparts.

On average last year, non-U.S. stocks produced a gain of 8.3% (as judged by the Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund

VEU,

). The U.S. stock market, in contrast, did three times better, gaining 25.7% (as judged by the Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF

VTI,

).

While this is certainly frustrating for investors who’ve diversified their stock holdings to include non-U.S. stocks, the fundamental case for such diversification remains as strong as ever — if not stronger.

The fate of the U.S. dollar

Perhaps the strongest single factor in explaining the relative performance of U.S. and non-U.S. stocks is the value of the U.S. dollar relative to foreign currencies. A weaker dollar helps the dollar-denominated performance of non-U.S. stocks, while just the opposite is the case when the dollar is stronger.

Consider the four calendar years since 2009 in which the United States Dollar Index

DXY,

declined. On average over those four years, non-U.S. stocks outperformed U.S. stocks by 1.9 percentage points (as judged by the same two exchange-traded funds mentioned above). In contrast, over the nine calendar years since 2009 in which the dollar index rose, non-U.S. stocks lagged U.S. equities by 11.7 percentage points, on average.

Given this strong inverse correlation between the U.S. dollar and non-U.S. equities, investors in non-U.S. stocks should be focusing on when the dollar will fall. Only if you believed the dollar has reached some permanently high plateau from which it will never decline would you be justified in reducing your international equity exposure. But such a belief is absurd: The foreign currency exchanges are a free market, just like the stock and bond markets. Nothing traded in these markets never goes down.

Value versus growth

There’s another factor that currently is influencing the relative performance of U.S. and non-U.S. stocks: where the markets stand in the pendulum swing between value and growth. Though over the past century value has outperformed growth, on average, the past decade has been a major exception to that pattern. U.S. equities have enormously benefited from this exception. Only if you think this exception will continue would you want to reduce your holdings of non-U.S. stocks.

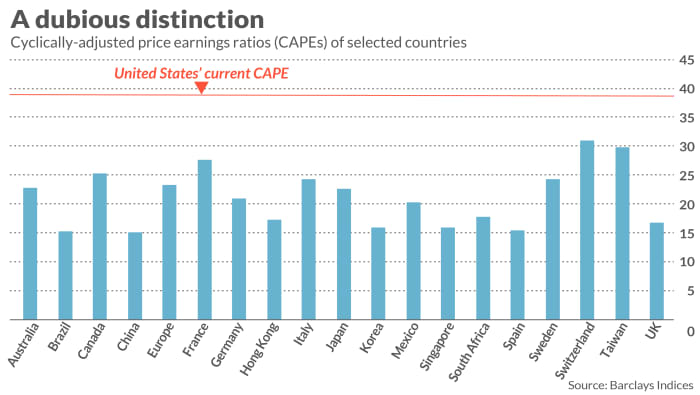

One way to put this value-versus-growth dimension in context is to compare the CAPE ratios of U.S. and non-U.S. stocks. The CAPE ratio, is the “cyclically-adjusted price/earnings” ratio made famous by Yale University professor Robert Shiller. It has one of the best track records historically in explaining and predicting the stock market’s subsequent 10-year return. And, despite assertions that it may have lost its explanatory power, it has just as good a track record over the past couple of decades as it did before.

As you can see from the chart below, the U.S. currently has the highest CAPE ratio of any developed country — much higher in fact. Compared to a ratio for the U.S. in the high 30s, Europe’s CAPE currently is in the low 20s. The United Kingdom’s is in the high teens. Unless the stock market has permanently severed its connection to corporate earnings, these other countries’ stock markets should eventually outperform the U.S. market.

When they do, you will be glad you held onto your international stocks rather than, as many currently are doing, throwing in the towel and confining your equity holdings to U.S. stocks only.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Value stocks now are beating growth by 10 points, but the easy money might be behind us

Also read: Buy the dip, says JPMorgan. ‘Markets can handle higher yields’