This post was originally published on this site

The Issue:

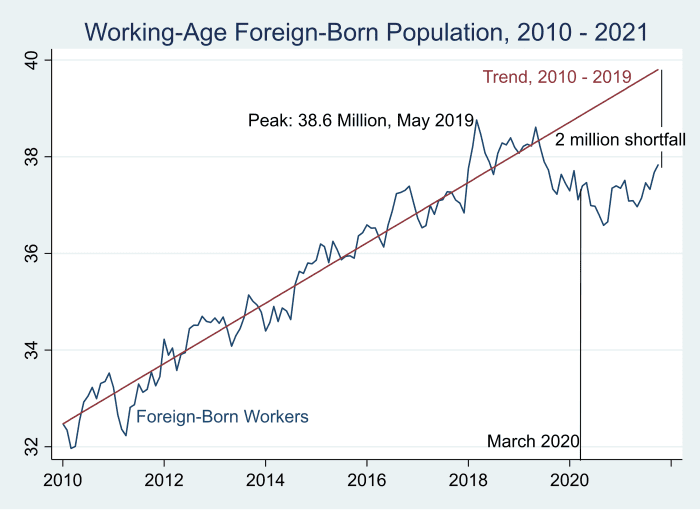

Due to increased restrictions on immigration and travel, which began with the COVID-19 pandemic in the early months of 2020, the net inflow of immigrants into the United States has essentially halted for almost two years. By the end of 2021 there were about 2 million fewer working-age immigrants living in the United States than there would have been if the pre-2020 immigration trend had continued unchanged.

Of these lost immigrants, about 1 million would have been college educated. The data on labor shortages across industries suggest that this dramatic drop in foreign labor-supply growth is likely a contributor to the current job shortages and could slow down employment recovery and growth as the economy picks up speed.

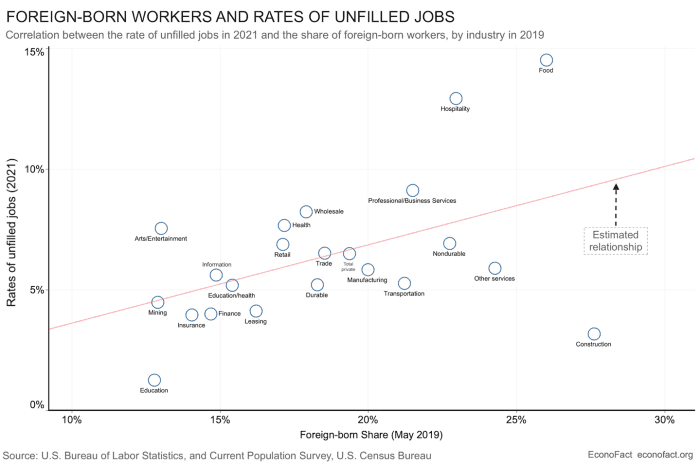

“Sectors that are especially reliant on immigrant workers had significantly higher rates of unfilled jobs in 2021.”

The Facts:

During the years 2020 and 2021, the number of immigrants arriving in the United States decreased substantially. In the early months of 2020 and in response to the COVID-19 health crisis, the Trump administration closed the borders with Mexico and Canada and placed restrictions on international arrivals. Visa processing at U.S. embassies and consulates around the world was also severely disrupted, leading to a dramatic decline in the inflow of foreign nationals on all types of temporary visas.

According to the Department of State, the slowdown in visa processing generated much fewer visa entries and a large backlog of more than 460,000 people with unprocessed visas as of late 2021. Similarly, the number of permanent residents arriving in the U.S. also fell substantially. Statistical estimates relative to the Fiscal year 2020 (from Oct. 1, 2019 to Sept. 30, 2020) indicate a decrease of immigrant visas by 45% and a decrease of nonimmigrant visas by 54% relative to the previous year.

The immigration pipeline has been closed, reducing the number of foreign-born people who could be working in the United States.

Econofact.org

This decline in immigrant and nonimmigrant visa arrivals resulted in zero growth in working-age foreign-born people in the United States. Prior to 2019, the foreign-born population of working age (18 to 65) grew by about 660,000 people per year, as reported in data from the monthly Current Population survey (see the chart above).

This trend had come to a stop already in 2019 before the pandemic, due to a combination of stricter immigration enforcement and a drop in the inflow of Mexican immigrants. The halt to international travel in 2020 added a significant drop in the working-age immigrant population.

“The loss of two million potential immigrants, of which a million are college educated, could impact productivity and employment in the long run.”

As of the end of 2021, the number of working-age foreign-born people in the United States is still somewhat smaller than it was in early 2019. Relative to the level it would have achieved if the 2010-2019 trend had continued, there is a shortfall of about two million people. A similar calculation done using Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly data on foreign-born individuals with a college degree indicates that of the missing 2 million foreign workers, about 950,000 would have been college educated, had the pre-2020 trend continued. This is a very substantial loss of skilled workers, equal to 1.8% of all college-educated individuals working in the U.S. in 2019.

As the U.S. economy recovered from the Covid-19 crisis in 2021 and job-creation increased, employers found it more difficult to fill jobs. Across sectors, these shortages are significantly associated with the loss of foreign workers. The recent economic recovery has seen more numerous job openings and jobs going unfilled for longer periods of time. In spite of upward pressure on wages in several sectors, such as hospitality and food-related services, the number of unfilled job openings relative to employment has remained very high.

Industries with a greater percentage of foreign-born workers have more job openings.

Econofact.org

The absence of foreign-born workers plays an important role in this. Those sectors that had a higher percentage of foreign workers in 2019 had significantly higher rates of unfilled jobs in 2021 (see chart above). Our estimates suggest that an industry that had a 10% higher dependence on foreign workers than another industry in 2019 saw a 3% higher rate of unfilled jobs in 2021.

The loss of foreign workers is not the only reason for the high rate of unfilled jobs. Increased retirement and increased bargaining power of workers are likely playing an important role. While more generous unemployment and welfare benefits introduced during the crisis may have discouraged workers from taking low-paying jobs in 2020 and early 2021, they do not seem to be the cause of current shortages, since most of those benefits expired by mid-2021. Recent anecdotal and preliminary evidence finds a push by workers for more job-flexibility, safety and, generally, better conditions causing resignations and contributing to unfilled job openings.

Moreover, increased retirement rates have contributed to the decline in available workers. A recent study finds that just excess retirement and reduced re-entry of retirees to the labor force has increased the share of retirees relative to the U.S. labor force by 1.3 percentage points in the last two years (compared to an annual rate of increase or about 0.3 percentage points prior to the pandemic).

These factors have affected labor availability, especially in low-paying manual-intensive jobs in sectors as food services and hospitality. The second chart shows that the rates of unfilled jobs in those two sectors are well above what is predicted by the statistical association across all industries between the rate of unfilled jobs and industries’ dependence on foreign workers, suggesting that other factors are at work in those sectors.

The loss of two million potential immigrants, of which a million are college educated, could impact productivity and employment in the long run. A recent study by one of the authors shows that college-educated immigrants are likely to work in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) sectors; these jobs are drivers of innovation and productivity growth. Additionally, research focused on the high-skilled STEM jobs shows that they are responsible for creating a job-multiplier effect at the local level, producing opportunities of up to 2.5 additional jobs for each additional employed high-skilled worker through local demand for goods and services and by companies expanding and hiring other workers.

In light of these effects, the loss of one million college-educated immigrants may leave the U.S. economy with lower productivity, which translates to lower growth. Applying the estimated job multiplier from the research referenced above to the observed loss of college-educated immigrants implies 2.5 million fewer jobs in those local economies where the immigrants would have worked.

The loss of immigrants could imply a large loss of entrepreneurship. Immigrants have a three times higher probability of starting firms than natives in the U.S., according to estimates from an article published in 2020. Immigrants are more likely to start small firms (with 0-10 employees) but also medium size and large firms (with 1,000 employees or more) relative to natives. Using the estimated entrepreneurship rate of immigrants from this study, two million fewer immigrants would imply a decline in firm creation, solely due to lack of entrepreneurs, corresponding to a loss of more than 200,000 jobs.

The loss of foreign college students will affect American educational institutions. Foreign college students are the part of the foreign-born population with the largest decline in the last two years. After decades of continued growth in foreign enrollment in American colleges and universities, peaking in 2018-19, their number dropped by 20% in 2020. This has had an adverse effect on higher education, one of the largest U.S. service exports.

Furthermore, foreign students, especially graduate students, have been very important contributors to U.S. research and innovation and patenting. Their absence could weaken the innovation and patenting potential of those universities, research institutions, and businesses that depend on cutting-edge research and innovation.

What this Means:

The shortfall of immigrants over the past two years has had immediate adverse consequences for filling jobs and also harms the long-run prospects for the U.S. economy. The drop in the number of foreign students and high-skilled immigrants is particularly concerning for the long-run effects on productivity, innovation and entrepreneurship.

The drop in the number of less-skilled immigrants can be contributing to the current shortages in several industries in which they had been highly represented. In light of this, the government should make an effort this year to facilitate the processing of nonimmigrant and immigrant visas to avoid further reducing the number of immigrants and the resulting negative economic consequences.

This commentary was originally published by Econofact.org — Labor Shortages and the Immigration Shortfall.

Giovanni Peri is an economics professor at the University of California Davis, with expertise is in labor economics, urban economics, and the economics of international migrations. Reem Zaiour is a Ph.D. candidate in the Economics Department at the University of California Davis, researching migration, labor and public economics.

More on the labor shortage

Coronavirus pandemic a factor as U.S. population grows at record-low pace