This post was originally published on this site

Inflation is expected to continue ripping along. At its policy-making meeting later this month, the Federal Reserve should move to tighten monetary policy much more quickly than it indicated at its December meeting.

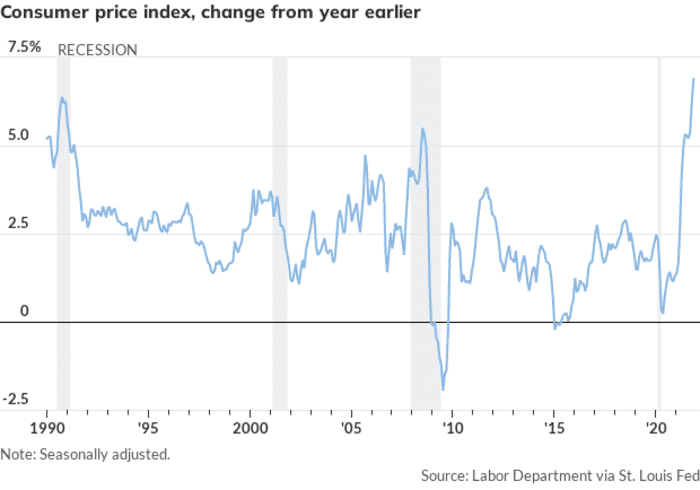

Headline inflation is running at 6.8%—the fastest pace in four decades.

MarketWatch

Since early November, gas prices

RB00,

have eased modestly but that’s after rising about 85% from their pandemic low. And gasoline, heating fuels and other energy only account for about 7.5% of the consumer price index.

Follow the latest news on inflation on MarketWatch

Rents are rising

Apartment rents and the imputed rent on owner-occupied homes constitute about one-third of the index and real-estate values are rising at nearly a 20% annual pace. However, owing to the logistical difficulties of canvassing landlords and homeowners, those price changes are factored into the CPI with a long lag.

The November CPI reported only a 3.8% annual jump in the cost of shelter but as huge rent increases from 2021 are fully factored into the housing component, look for it to jump at the highest rate in decades and keep reported headline inflation elevated in 2022.

Rex Nutting: Inflation is running rampant in the U.S.—here’s where it is, and isn’t

More important, lumber prices for new home construction are rising again, and landlords are seeking big rent increases as leases renew. Construction costs and market-observed rent increases will keep the momentum rising on the cost of shelter in the CPI through at least 2023.

Farmers are bearing huge jumps in costs for fertilizer, machinery and other materials that will further drive up prices for bread, milk, meat and dairy. Long-term drought conditions, are causing a realignment of agriculture in California that should pressure almond, fruit and vegetable prices. Similar conditions in the tropics are driving up coffee prices

KC00,

Supplies disrupted

Global supply-chain disruptions will continue, and transportation disruptions will interrupt supplies of consumer goods and components for U.S. and European manufacturers.

Shortages of chips won’t abate soon, and uncertainties regarding pandemic-induced changes in consumer purchasing patterns have discouraged investment in new capacity elsewhere.

According to an analysis by the data analytics firm DataWeave, MSRPs are up 15% and discounts are fewer. Grocery suppliers are planning significant price hikes.

The shift toward onshoring and near shoring, owing to the geopolitical risks of relying on China, will raise costs and prices too.

Low-cost supplies

The Trump-Biden ambivalence toward revitalizing the World Trade Organization and entering into new trade agreements marks a decided brake on the momentum of globalization and will ultimately translate into reduced reliance on least-cost suppliers and higher prices for manufactured products.

Dealing with climate change and other adjustments in what we consume and how we make products—from electric vehicles to switching existing homes from natural gas and heating oil to electric heat pumps—will raise the cost of just about everything as we move through the balance of this decade.

President Joe Biden’s policies that discourage oil and gas production have empowered the social investing movement. That is pushing up the cost of capital in the petroleum sector and curtailing American production.

The March 2021 $1.9 trillion stimulus package was irresponsible. The money injected into the economy during the Trump presidency had hardly worked its way through and too much new money was dispersed to families who didn’t need it.

The resulting savings overhang—the money that is now chasing too few goods—will likely last into 2023. If the Democrats manage to pass some of their social spending and climate change proposals, that kind of reckless macroeconomic policy will continue to overheat demand for the rest of the decade.

Wage-price spiral

Wages are rising—but not fast enough. According to the Atlanta Fed, by about 4.3% in the last year.

Surveys by the New York Fed and Conference Board indicate consumers expect prices to rise at least 6% over the next year, whereas businesses are planning to only raise wages 3.9%.

With labor markets tight, we can expect workers to continue job hopping. We may not have the union power we did during the 1970s, but the much larger white collar workforce of our modern era has much better information about what the boss pays and bargaining power.

All that’s a recipe for a self-sustaining wage-price spiral.

The November Fed decision to more quickly taper bond purchases but not end those until March—and then perhaps raise interest rates—still adds stimulus.

The Fed should stop bond purchases and raise interest rates now. Paul Volcker acted decisively to break inflation in 1979 and the early 1980s, and Chairman Jerome Powell should push up the federal-funds rate at least a quarter point at each meeting starting on Jan. 29.

Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

More from Peter Morici

Digital dollars are coming, but is the Fed ready?

Powell and Biden are rolling the dice on inflation and growth