This post was originally published on this site

The best economics textbook may soon be a video game. The next Warren Buffett is probably sitting on a couch somewhere in the world right now, holding not stocks, bonds, or crypto — but a controller.

When I was a kid in the early 80s, back when the only global pandemic everyone seemed worried about was Pac-Man fever, they told us video games would rot our brains, that playing them would make us somehow both hyper-violent and hyper-lazy.

That was all mostly nonsense, it seems. Instead, as the gaming industry has overtaken movies and sports in America — as games themselves are the site of the sort of artistic explosion and innovation we saw in modern art, music, and movies in the 20th century — there’s also a strong case to make that rather than rot our brains, video games can enrich them. Games can help us get better at managing money and life.

“That’s just a theory – a game theory,” as Matthew Patrick, one of my sons’ favorite Youtubers tells his 14 million subscribers at the end of each video. But I decided to put it to the test.

The game of life

There’s a quote sometimes attributed to Ted Turner, that “life is just a game. Money is how we keep score.” I’ve always found this to be an obnoxious sentiment, but Edward Castronova, an economist and professor of media at Indiana University, who has studied the virtual economies of video games, says people have been comparing life to games for thousands of years — and there’s some truth to it.

“The phrase life is a game does not mean that life is silly,” he writes in “Life is a game: What game design says about the human condition,” his fascinating and delightfully weird book on the subject. “It means that life presents all people with choices, and those choices — combined with the inevitable randomness produced by the choices of others as well as Nature herself — come back in terms of gains and losses.”

Money is at least one way we keep score. In 2020, when the game “Animal Crossing” became a huge hit, many marveled at how suddenly kids and adults across the world were inadvertently learning about how prices and arbitrage work.

This should come as no surprise, Castronova, who has run experiments on prices in games, told me. “I have never seen anything in a video game that violates any known or accepted economic theory. Economic behavior in games is exactly like economic behavior in life,” he said.

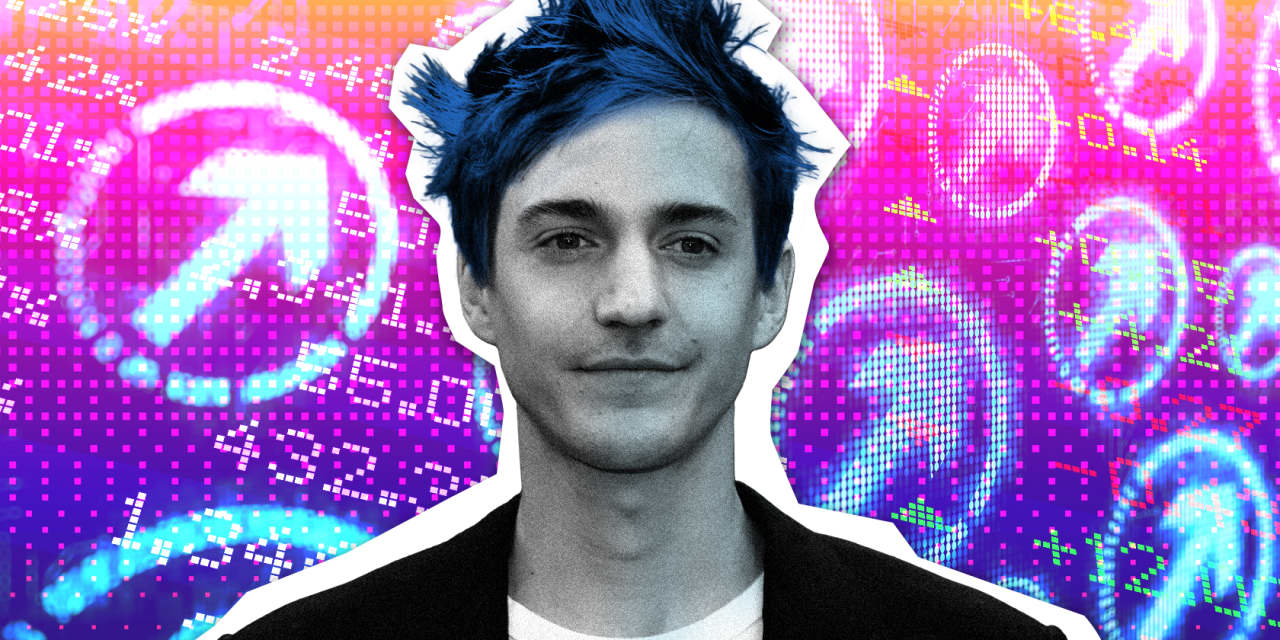

Ninja, star

What do gamers make of the idea that games teach players about economics and managing money? I asked Tyler Blevins, better known as Ninja, one of the world’s most successful pro gamers, who has earned millions streaming his play on Twitch and YouTube.

“I mean, V-Bucks, dude,” he said, referring to the virtual currency in the game that made him famous, Fortnite. “So they just added this thing called gold. And basically, the more things that you break down and, opponents, you eliminate, the more you build gold over time, and then you can use that gold to upgrade your weapons.”

In role-playing games you learn how to trade, and even how to deal with inflation, Ninja told me.

But even in a first-person shooter like Fortnite, there is a lot of strategy in how to manage your gold and resources, Ninja said. “It is basically like budgeting. I guarantee you, there are younger players that are thinking the exact same thing, even though they don’t know it — like, ‘I only have enough to upgrade my shotgun once’ — they’re literally budgeting.”

Ninja spent years honing his games skills, coordinating movement of mouse, eyes, and fingers to move and aim faster and more accurately than his competition. He attributed his success to talent and hard work. When I asked him about the role luck played in his own rise to gaming stardom or how much luck matters in games in general, he sounded like so many CEOs or other stars I have interviewed over the years.

“There’s almost no luck in competitive gameplay at the high level, really,” he said.

Pay to win

Luck may not be a factor, but in the economies of games, players care a great deal about fairness. There are games that allow players to buy an edge by spending more money, sort of the equivalent of a one-percenter buying their kid into USC.

“Those games are what we call pay-to-win games and that no one really likes,” Ninja said. “I mean, any true gamer is going to cringe when they hear that a game is like that. While there are V-Bucks in the game, it’s free to play. Fortnite is not a pay-to-win game.”

Gamers prefer their virtual worlds to be meritocracies, Castronova said. “Designers have to strike a balance between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome. Everyone should start with the same amount. They care about the wage rate, the amount of stuff you can get per hour. What doesn’t bother them is equality of outcome.” That is, players with more skill or those who put in more time should be able to accumulate more advantages.

Game developers have been putting economists on staff to get these virtual economies right. I spoke to Justin T.H. Smith, a data scientist and economist at Electronic Arts.

“Games that do that well communicate to the player we appreciate the time and effort you are putting into the game,” he said. “Showing players they are valued is a tough thing to do. And it’s why we need to get the currencies and economics right. People make tradeoffs between time and money and risk, just as they do in real life.”

There are lessons for policymakers here about what makes a fair and equitable society, and also what could spark the next revolution, Castronova said. “Social science uses game-like models to analyze real situations. More generally, we can say that all games are models. Every game tries to model some aspect of reality. Chess is a model of war. Poker is a model of bargaining. Hockey is a model of a Canadian saloon brawl.”

For much more on how professors and high school teachers are using games to teach economic ideas in the classroom, listen to the new episode of our podcast, “The Best New Ideas in Money.”

Play what you know

Ninja does not have any pretensions of becoming the next Warren Buffett. He says that his approach to video games is not unlike his approach to his money: He’s methodical, he does his homework, and he practices – a lot. He trusts the running of his business to his wife, Jess, and to the professionals. Games have definitely helped him evaluate money decisions though.

When approached with an investment opportunity recently in NFTs and crypto, he was interested, but ultimately balked. “They explained the entire thing to me, man. And I know that’s potentially the future, but the whole thing was too confusing to me.”

Instead he made an investment in something he does know and understand. “My investment in Pokemon cards lately has been just out of this world. They’ve been skyrocketing.”

Warren Buffett would approve of that game play.