This post was originally published on this site

What’s in and what’s out for 2022 at the Fed?

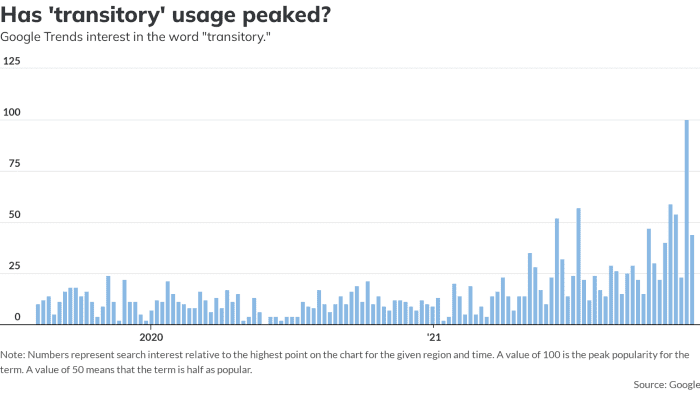

It’s pretty clear that “transitory” is out.

Uncredited

Actually, economists think the word “transitory” got a bad rap.

It is not a bad way to describe inflation — as long as you give people more information about the time frame you have in mind, they said.

“I think higher inflation is transitory but I think it will last another year. A lot of people don’t define that as transitory,” said Megan Greene, global chief economist at Kroll Institute.

Always seeking the most wiggle room, the Fed didn’t really define transitory when they first used it in April.

But investors seemed to generally assume it meant that inflation would start to come down by the end of this year.

That didn’t work out.

The core rate of the Fed’s favorite inflation gauge – the personal consumption expenditure index – surged to 4.1% in November. That’s the highest since 1990.

This caused Powell to ditch the term.

“It is probably a good time to retire the word,” Powell told Senators at a recent hearing.

So, what’s in ?

In it’s place, Brian Bethune, an economics professor at Boston College, said he thinks the Fed will lean toward words that indicate inflation is “persistent.”

Tim Duy, chief economist at SGH Macro Advisors, thinks Powell will shy away from labels and give more of a description, something like “we anticipate that these inflationary pressures will ease over time.”

Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, thinks the Fed will lean toward persistent, with emphasis on the uncertainty.

When it was noted that “tenacious” was a synonym for persistent, economists did not think the Fed would jump at the chance to use it.

The core rate of PCE inflation may cool somewhat next year but it is not a “slam dunk” that it will get back to a 2.5% rate that would be more tolerable for the Fed, Bethune said.

Businesses have all done their business plans for 2022 and they have added prices increases. As a result, the Fed is aiming to impact business plans for 2023, he said. If that doesn’t work, “we’re looking at a fairly large tightening cycle,” Bethune added.