This post was originally published on this site

The big news from the Federal Reserve’s meeting Wednesday wasn’t that it’ll stop buying bonds to stimulate the economy or that it’s now signaling three increases in its benchmark lending rate in 2022. Those short-term policy decisions had been well-telegraphed by Fed officials over the past month.

No, the big surprise is that the gargantuan, change-averse Fed has turned 180 degrees in its view of inflation.

The Fed’s statement Wednesday and the accompanying materials show that the doves — the policy makers who generally believe that the risk of inflation is overblown — have completely surrendered. Everyone’s a hawk now. There are no doves at the Fed anymore.

Fed monetary-policy makers unanimously agree that fighting inflation is their No. 1 job. They may disagree on the tactics or the timing, but not on the strategy of vanquishing inflation soon. The Fed is on a war footing, and inflation is the enemy.

For 30 years, the doves had been right: Inflation wasn’t the biggest threat to the economy; unemployment was. The doves fought an ultimately successful battle to force the Federal Reserve to consider the very real costs that unemployment forces upon society and the many individuals whom the economy was leaving behind.

But now effects of the coronavirus pandemic have forced even the doves to accept that inflation is a bigger threat than unemployment. That’s a huge change in an institution that doesn’t like change.

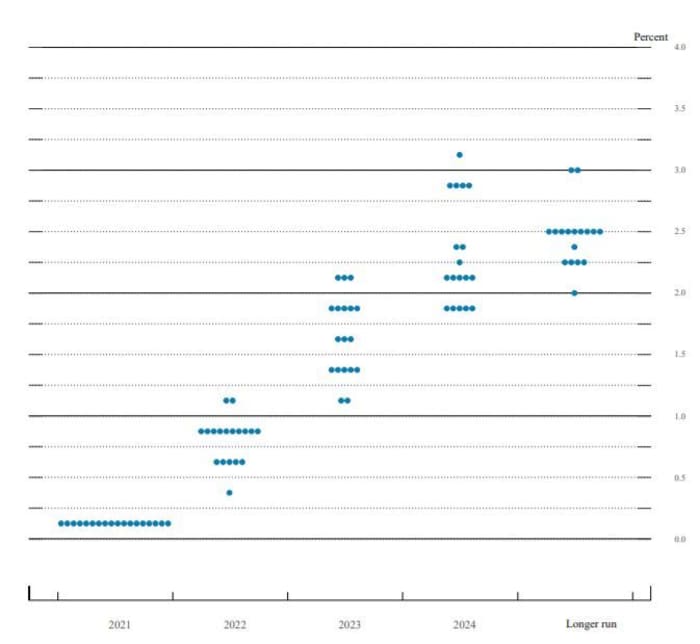

How do we know the doves have metamorphosed into hawks? Look at the dot plot, a chart the Fed releases every three months that shows the anonymous individual forecasts of each monetary-policy maker for the level of the federal funds rate at the ends of the next several years.

Most analysts correctly focus on the median forecast for the coming year, but I’d like to redirect your attention briefly to the medium-term forecasts of the outliers, the most hawkish and dovish members of the Fed, to show how much the battlefield inside the Fed has changed since that horrendous consumer-price-index reading of Nov. 10. That report changed everything at the Fed.

The December dot plot shows that all Fed policy makers believe interest rates must be raised until inflation is vanquished.

Federal Reserve

In the latest forecasts released Wednesday, the most hawkish members raised their medium-term forecasts modestly from 1.63% to 2.13% at the end of 2023, and from 2.63% to 3.13% at the end of 2024. The five most hawkish members now think the Fed will have to push the fed funds rate above its assumed long-run equilibrium of 2.5%.

But the doves completely tore up their previous forecasts. The five most dovish members were forecasting between zero and two rate hikes by the end of 2023, but now they expect four or five. By the end of 2024, they had been forecasting between two and four rate hikes; now they expect seven.

Clearly, even the most dovish Fed officials now believe the fed funds rate must go up a lot to vanquish inflation. Before, they thought inflation would come down all by itself.

This means that inflation no longer gets the benefit of the doubt. It’s been proven guilty, and even the doves will prosecute the war until victory is won. For the inflation doves at the Fed, Nov. 10, 2021, was bit of like Dec. 7, 1941: Time to go to war.

Rex Nutting is a columnist for MarketWatch and has covered economics and the Fed for more than 25 years.

Greg Robb: Fed accelerates taper of bond purchases, eyes three interest-rate hikes in 2022

Andrew Keshner: What the Fed decision means for your wallet — and your credit card bill

Jeffry Bartash: Fed finally steps up to fight high inflation after downplaying rising prices for months

Market Snapshot: Dow, S&P 500 post best day in a week after Fed tapers bond buying aggressively, pencils in 3 rate hikes next year