This post was originally published on this site

For months, the $22 trillion Treasury market has flashed warnings about the risk that Federal Reserve policy tightening, aimed at reining in persistently high inflation, might lead to slower U.S. economic growth.

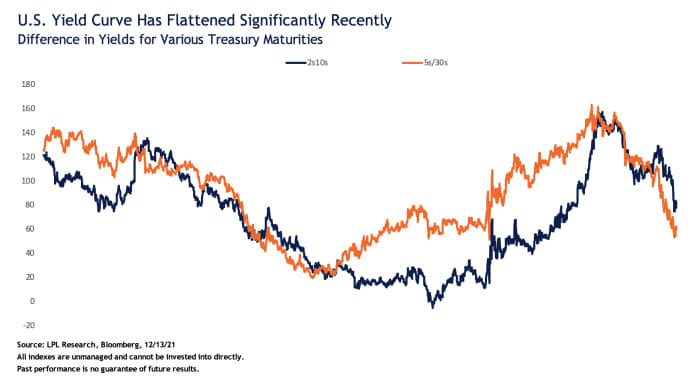

The signs have been evident in the flattening of the widely followed spread between two- and 10-year yields, as well as the gap between 5- and 30-year maturities. What’s more, the long end of the Treasury curve has remained inverted, with the 20-year yield trading above its 30-year counterpart.

Now the risk of a broader yield-curve inversion, which might signal the likely onset of a U.S. recession, is on the radar for analysts heading into 2022. Though some say such a development is not likely to occur until next year or even 2023, the curve has already significantly flattened on stronger-than-expected U.S. inflation readings, continued worries about the pandemic, and a bit of hawkish talk by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell.

Wednesday brings the Fed’s policy update and analysts expect central bank officials to pencil in as many as nine rate hikes through 2024, in what’s known as their “dot plot.”

“There’s little chance that the dots alone would put the curve much at risk, but the risk of yield curve inversion is going to be the big story of 2022,” said Tom Garretson of RBC Wealth Management in Minneapolis. “Even though there’s a tendency to dismiss flattening yield curves in a low-yield environment, another inversion is inevitable at some point. With a flattening trend firmly in place, the only question now is, how long does it take?”

RBC Wealth isn’t ruling out the possibility of a broader inversion late next year, even though its base-case view is that Fed policy makers can still manage to dodge such a development by “sending a hawkish tone now, without acting on it later”, Garretson, a senior portfolio strategist, said via phone. “That, in itself, can temper some inflationary pressure and expectations, and gives them breathing room while they don’t necessarily have to follow through with multiple rate hikes next year,” he says. In such a situation, “the yield curve can resteepen modestly.”

Want intel on all the news moving markets? Sign up for our daily Need to Know newsletter. Use this link to subscribe.

As of Tuesday morning, the widely followed spread between two-

TMUBMUSD02Y,

and 10-year

TMUBMUSD10Y,

Treasury yields had shrunk below 80 basis points, according to Tradeweb data. The spread managed to narrow by almost 20 basis points over the course of a few days earlier this month, as investors assessed the spread of the omicron variant of coronavirus.

Meanwhile, the gap between 5-

TMUBMUSD05Y,

and 30-year yields

TMUBMUSD30Y,

narrowed to under 60 basis points on Tuesday, according to Tradeweb, remaining around the flattest levels since March 2020 when the virus triggered economic lockdowns.

LPL Research, Bloomberg

At current levels, the 2s-10s and 5s-30s spreads are still some way from inversion, though the flattening momentum is clear.

For the curve to continue flattening soon after the FOMC’s dots are released Wednesday, Fed officials would have to pencil in at least four rate hikes per year from 2022 to 2024, or more than what many analysts are projecting, said Lawrence Gillum, a fixed income strategist at LPL Financial who is based in Fort Mill, South Carolina.

“We do not think inversion is a near-term story, but one we will be watching for the next few years, with 2023 as the bigger risk,” Gillum said via phone. “But we could see inversion sooner if the Fed starts to be more aggressive than what’s priced into the market.”

Inflation is the wild card and much will depend on whether price pressures start to moderate in coming months. On Tuesday, Treasury yields edged higher as Federal Reserve policy makers started their two-day meeting and the latest read on U.S. wholesale prices showed inflation is getting worse.

There’s a “big risk” that “after falling behind the inflation curve, the Fed now risks getting too far ahead” going forward, said Garretson of RBC Wealth. However, RBC Wealth sees a low likelihood that the Fed will use Wednesday’s policy update to “push the tightening narrative beyond what’s already priced by markets.”

Even so, a dot plot that reflects a sooner-than-expected start to the Fed’s next rate-hike campaign should lead to more flattening over time, even if the curve periodically re-steepens on economic surprises, according to Ben Emons, managing director of global macro strategy at Medley Global Advisors in New York. Still, “the market is not yet settled on the idea of a broader inversion, and much will depend on the next six months as the Fed prepares to lift off,” or raise the policy rate target for the first time, Emons says.

The last time the 2s-10s spread inverted was in August 2019. A U.S. recession followed in February 2020 when the coronavirus pandemic began. The 5s-30s gap has not inverted, on a closing basis, since March 2006, according to Tradeweb.