This post was originally published on this site

Beth Vial only learned she was pregnant toward the end of her second trimester.

This was astonishing news: A few years before she began her freshman year of college in 2017, Vial, now 27, of Portland, Ore., had been diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and irritable bowel syndrome. A doctor told her she wouldn’t be able to get pregnant without medical intervention, and said she would need to go on birth control to balance her hormones.

But complications with her parents’ health insurance at the time delayed Vial from filling her birth control prescription for over a week.

“I was in a long-term, committed relationship, and it was in that window that I got pregnant,” Vial said. “I was never told there was a risk of pregnancy — and because of PCOS, I didn’t menstruate, so I showed no obvious signs. I was completely unaware that I was pregnant.”

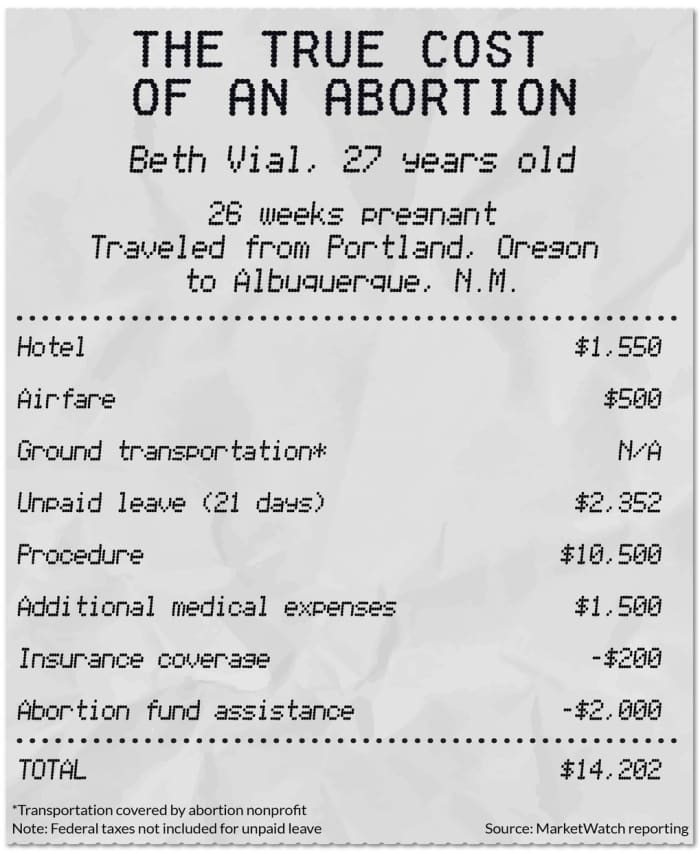

Seeking abortion care would wind up costing Vial thousands of dollars in total.

The most conservative U.S. Supreme Court in decades heard oral arguments Wednesday on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — concerning a Mississippi law that would ban nearly all abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy — and conservative justices signaled they were open to upholding the restrictions. The case will determine whether states can ban abortions before “viability,” meaning the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb, typically around 24 weeks.

Lower courts had blocked the ban from taking effect based on Supreme Court precedent that states can’t prevent people from terminating a pregnancy before viability. The state of Mississippi is asking the court to overturn Roe v. Wade and let individual states decide the legality of abortion.

“‘I was completely unaware that I was pregnant.’”

Abortion-rights supporters fear that overturning or weakening the nearly 50-year-old precedent could increase the financial burden for people seeking abortion care and rock the foundation of reproductive rights in the U.S. Meanwhile, anti-abortion advocates are looking to their “post-Roe strategy” and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on federal lobbying in the third financial quarter, according to OpenSecrets. The Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group, did not return a MarketWatch request for comment on this story.

“Mississippi’s law, if upheld, brings us much closer to where we ought to be,” Marjorie Dannenfelser, the president of the Susan B. Anthony List, said in prepared remarks Wednesday outside of the Supreme Court. “This is America’s chance to step back from the brink of madness after all these long years. To turn the page on Roe’s onerous chapter and begin a more humane era — one where every child and every mother is safe under the mantle of the law.”

‘It was incredibly isolating’

Vial considers herself fortunate. Coping with an unplanned pregnancy and still being able to access care for a later abortion would have been more challenging today, she believes.

Restrictive abortion laws have proliferated in recent years in the South and Rust Belt, and many people are already unable to access abortion care. For example, a Texas law also currently before the Supreme Court banned abortions after cardiac activity can be detected in the embryo — as early as six weeks, at which point many people are unaware they’re pregnant. Supporters of these measures call them “heartbeat bills,” a term many healthcare professionals call inaccurate.

“I chose to advocate for abortion access because when I was going through my experience, it was incredibly isolating,” said Vial, a program coordinator for WeTestify, an advocacy organization dedicated to the leadership and representation of people who have abortions. “You hear a lot of stories about women not knowing they were pregnant until they are in labor. I just happened to find out within the window that I could access care.”

But the journey wasn’t easy. Even though Vial resided in Oregon — a state whose policy has been supportive of abortion rights — she sought an abortion before the state’s 2017 Reproductive Health Equity Act, which expanded access by requiring private insurers to cover abortion care at no out-of-pocket cost, went into effect. The fact that abortions later in pregnancy are still controversial and stigmatized added to the difficulty.

The medical school that Vial initially sought out for care wasn’t openly advertising abortion services. Given her medical history and the fact that she was toward the end of her second trimester, accessing abortion care required a majority board approval from the university’s natal department.

“I was only able to get two of the five doctors to approve my procedure, so they referred me to a clinic in New Mexico,” Vial said. “I was only a week away from the gestational limit — so I had a week to figure out how I was going to pay for everything.”

‘I chose to advocate for abortion access because when I was going through my experience, it was incredibly isolating,’ says Beth Vial.

Beth Vial

The average cost nationwide of a surgical abortion at 10 weeks was $508 in 2014, according to one nationwide study on abortion costs, though the cost could range from $75 to $2,500. Early medication abortion at 10 weeks cost $535 on average and could range from $75 to $1,633.

But abortion costs also vary across states, providers and other factors, and can increase significantly as a pregnancy progresses. According to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive-health think tank that supports abortion rights, an abortion at 20 weeks’ gestation can cost almost 2.5 times as much as an abortion at 10 weeks.

For Vial, who had her abortion at 26 weeks, the surgical procedure came with a $10,500 price tag. Additional medical expenses, airfare to Albuquerque and lodging would drive up costs another $3,550. (Abortions at or later than 21 weeks are uncommon and make up just 1% of all abortions in the U.S., according to KFF, a healthcare think tank.)

“I had just started working a new job and I ended up taking three weeks off work, so I lost a paycheck and a half,” Vial added. “I was able to get help from my local abortion funds [in Oregon] and a loan from a family friend. I was very fortunate to have that kind of wealth in my proximity, because without it, I wouldn’t have been able to access my abortion.”

Increasingly restrictive abortion policies pose an economic impediment to many women. And roughly half of women who have abortions live below the federal poverty level, making it even more financially arduous for them to cover basic expenses while traveling to receive care.

Restrictive abortion policies can be costly for the economy too, research suggests: The Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit, estimates that state-level abortion restrictions cost the country $105 billion a year by decreasing labor-force participation and earnings among women ages 15 to 44, and increasing time off and turnover. In Mississippi, that means about $1 billion in annual economic loss.

Between 1973 and this past October, states enacted more than 1,300 abortion restrictions, according to Guttmacher. While 16 states have demonstrated support for abortion rights, 29 have policies considered “hostile” and five are in the middle ground.

Barriers to abortion access have led to a surge of women forced to travel across state lines to access care, and some clinics are preparing for an even larger increase in out-of-state patients in the wake of the Supreme Court hearing. If Roe were to be weakened or reversed, some 26 states would be “certain or likely” to quickly prohibit abortion, according to one Guttmacher analysis — meaning any of the estimated 36 million women of reproductive age in those states seeking an abortion would need to travel longer distances for out-of-state care.

Read more: Nearly half of women who have abortions live below the federal poverty level

“Over the last couple of years we’ve seen an increase in out-of-state patients coming for care, but just in the last couple of months, we’ve seen a 30% increase in out-of-state patients,” Kristen Schultz, the vice president of operations and strategy at Planned Parenthood of Illinois, told MarketWatch. “We’ve certainly had an increase in patients directly from Texas, but in September we saw patients from 12 different states.”

Carol Tobias, the president of the anti-abortion National Right to Life Committee, told MarketWatch, “the life of an unborn child shouldn’t end, so I would encourage a woman to seek out the help that’s available in her community.”

“If she really thinks she cannot take care of the child, then release the child for adoption,” Tobias said. “I don’t think a woman should be traveling hundreds of miles and spending thousands of dollars to kill her baby.”

‘At 20 years old, I didn’t want to be a parent,’ says Maleeha Aziz.

Maleeha Aziz

‘I was naive and thought it would be easier’

Shortly after moving to Dallas, Texas from Pakistan in 2013, Maleeha Aziz, 28, found out she was pregnant.

“At 20 years old, I didn’t want to be a parent. I was fairly new here and didn’t know how abortions worked,” Aziz said. “I was naive and thought it would be easier — I didn’t think I would have to travel to Colorado Springs.”

After a family member referred her, Aziz ended up going to a “crisis pregnancy center” — a type of facility that typically offers resources and tests, but works to dissuade people from seeking abortions — instead of an abortion clinic.

“I don’t think my cousin knew at the time, but they claimed to do free sonograms,” Aziz said. “I didn’t have enough money, or insurance, so I needed a place that would give me an ultrasound because I didn’t know how pregnant I was.”

Due to an existing medical condition, a surgical abortion or any invasive procedure wasn’t an option for Aziz — leaving medication abortion the only choice on the table. After being misinformed by the clinic that medication abortions were banned in Texas, she had to act quickly. (Just weeks after signing into law the near-total abortion ban, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, signed a separate bill into law narrowing the window for access to abortion-inducing medication. That law goes into effect Thursday.)

“I found out that I was nine weeks [pregnant] and I got out of there,” Aziz said. “I had a complete meltdown and started crying because I needed to go somewhere to have a medication abortion.”

Abortion pills, along with additional medication, would run Aziz around $860, while lodging and travel combined would add another $714 to the bill.

With financial assistance from her family, Aziz was able to get her abortion pills and travel costs fully covered. Her total cost, after accounting for lost wages, came out to $2,414. But Aziz noted that the true total cost of her abortion also included the costs for her partner to travel with her, because her pregnancy made her too sick to travel alone.

“A support person is a necessity for many people,” Aziz said.

Aziz, who currently works as a community organizer at the Texas Equal Access Fund, which provides funding to low-income Texans seeking abortions, testified before Congress in September that Texas’s ban on abortion after six weeks’ gestation had created a “logistical nightmare.” She called the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for most abortions and which abortion-rights supporters say disproportionately impacts low-income people and people of color, “classist” and “racist.”

“No one should have to put their trauma on display just to get legislators to realize the depravity of the law that they passed,” said Aziz, who is also an abortion storyteller with We Testify. “I wanted to truly highlight what costs are associated with having to travel out of state, and I wanted to paint them a picture through my experience.”

The consequences of being denied an abortion

The economic costs of restrictive abortion policies are not limited to women who have to travel for abortion care. Women who are denied a wanted abortion also face greater odds of their financial well-being being negatively affected.

A 2020 paper using data from the Turnaway Study, which tracks the impacts of unwanted pregnancy on women’s lives, found that abortion denial increased women’s amount of past-due debt by 78%, or about $1,750. The incidence of negative “public records” such as bankruptcy, evictions and tax liens on their credit reports increased by 81%.

“‘Women who were denied abortions were more likely to report that they didn’t have enough money to pay for basic living needs like food, housing and transportation, and they were less likely to have full-time employment.’”

The Turnaway Study has also concluded that women who are turned away from abortion services experience long-term negative socioeconomic effects, and have four times greater odds of having their incomes fall below the federal poverty level.

“When we follow people over time, we’ve seen big economic differences,” Diana Greene Foster, a professor and demographer who leads the Turnaway Study, told MarketWatch. “Women who were denied abortions were more likely to report that they didn’t have enough money to pay for basic living needs like food, housing and transportation, and they were less likely to have full-time employment.”

Anti-abortion advocates like Tobias, meanwhile, say that having an abortion can take an emotional toll on women down the line, despite research that shows having the procedure does not increase women’s risk for experiencing mental health conditions. “There are costs involved in an abortion that can’t necessarily be monetized — there are psychological and emotional aftereffects as well,” Tobias said.

Brittany Mostiller says carrying her third pregnancy to term created a financial and emotional hole from which she would spend years digging herself out.

Brittany Mostiller

Brittany Mostiller, who was unable to afford an abortion 14 years ago, knows firsthand the economic impact of being denied the procedure. Carrying her third pregnancy to term created a financial and emotional hole from which she would spend years digging herself out.

“I already had young children and I was living with my sister in a two-bedroom apartment,” Mostiller said. “Once I found out the procedure would cost $600, I knew immediately that I could not raise that money — and I wasn’t willing to reach out to any family, because I didn’t want to be shamed for it.”

As a single mom, struggling to make ends meet became the norm. Meanwhile, managing postpartum depression “was really hard, because I had to love and care for a child that I didn’t want when I was struggling to love myself,” Mostiller said.

Now a mother of four, Mostiller, 37, is a leadership coordinator for the National Network of Abortion Funds. She uses her experience to help educate women and raise donations for local abortion funds throughout Chicago, where she feels the need has never been more urgent.

“We have seen an uptick in people traveling, but it’s not new,” Mostiller said. “A lot of folks have been living in a post-Roe reality for a long time, but there are certainly more who are now going across state lines to get the care they need.”