This post was originally published on this site

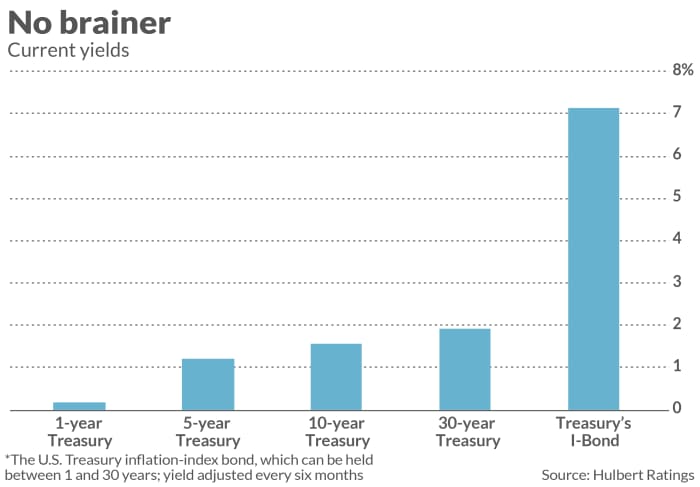

How would you react if your financial adviser tried to sell you a U.S. Treasury yielding 7.12%?

You’d undoubtedly be skeptical, since if something seems too good to be true it probably is.

In this case, however, your skepticism wouldn’t be justified.

Read: This simple investment can earn you more than 6% with no risk

I’m referring to a unique kind of savings bond issued by the U.S. Treasury that is indexed to inflation. Known as an I-Bond, its interest rate changes every six months (on May 1 and Nov. 1) according to the Consumer Price Index’s trailing 6-month change. When the Treasury at the beginning of this month set the rate that will be in place until May 2022, it was 7.12%.

Uncredited

Is there a catch? Perhaps, though you may consider them to be fairly small. Here are the details:

- The current rate of 7.12% isn’t locked in forever, since the I-Bond rate is reset every six months. If inflation through next May is a lot lower, for example, then the interest rate the I-Bond will earn from May through November of next year will be lower as well. However, with the latest CPI number released this week showing that inflation has risen to a 31-year high, the risk of the May 2022 rate being a lot lower seems remote at this point.

- Actually, the I-Bond interest rate is the sum of two different rates: The first, a fixed rate, is set when you purchase it. The second is the inflation adjustment, and this is the rate that changes every six months. Currently the fixed rate is set equal to 0%. If the Treasury at some point in the future were to increase this fixed rate on newly issued I-Bonds, you could cash in the I-Bonds you already own and purchase a new one. (Though you might have to pay a small penalty, as described below.)

- The way to think about the I-Bond is that it provides a guaranteed real (or inflation-adjusted) yield. Since the fixed rate portion of its rate is guaranteed not to be negative, you at a minimum will always earn as much as CPI inflation. This makes I-Bonds preferable to TIPS, which currently trade at negative real yields.

- You can’t buy unlimited quantities of I-Bonds. You’re limited to buying $10,000 per year per Social Security number; a married couple could therefore buy $20,000 per year. You’re also allowed to purchase an additional $5,000 per year with your tax refund.

- You can’t cash in your I-Bond in the first 12 months after purchase. And thereafter if you redeem it before the fifth anniversary of your purchase, you will pay a penalty equal to three months’ worth of interest.

- You can’t purchase an I-Bond in your IRA. But that’s hardly a defect, since you only pay tax on the I-Bond interest when you redeem it. So in that sense an I-Bond is like an IRA, since your interest accumulates tax-free. Furthermore, I-Bond interest is exempt from state and local income taxes.

How might you use I-Bonds? For insight, I reached out to Zvi Bodie, who has done as much as anyone, if not more, to champion I-Bonds. Bodie, now retired, was for four decades a finance professor at Boston University. In an interview, he suggested two major ways in which I-Bonds can play a valuable role:

- As a portion of your emergency funds. I-Bonds’ yields are far better than the near-zero rates earned by most money-market funds, even after taking into account the three-months-of-interest penalty when redeeming in the first five years. And they’re 100% safe and, provided you hold for a year, are completely liquid.

- As part of the fixed income portion of your retirement portfolio. Though you can’t buy a huge chunk of I-Bonds at any one time, you can gradually build up a large portfolio of them. Imagine that you and your spouse, both 20 years away from retirement, start a program of each year buying your maximum allotment of I-Bonds. Such an approach is consistent with the standard financial planning advice to gradually reduce your equity exposure as you get closer to retirement. In my hypothetical case, your total I-Bond holdings at retirement will equal $500,000 (plus accrued interest). Unless your retirement portfolio is in the many millions, your I-Bond holdings would represent much (if not all) of your desired fixed income allocation.

The bottom line? I-Bonds may not be as exciting as a get-rich scheme with meme stocks or cryptocurrencies. But they arguably will do more for your long-term financial security.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.