This post was originally published on this site

This article isn’t an anti-tax manifesto. Nor is it a suggestion that city governments bet big on some farfetched financial markets scheme.

What it is: a spotlight on a proposal from a group that’s not exactly a household name, dealing in what may seem to be an arcane topic — except that their idea just might have the ability to change nearly everything about the American economy and civil society.

The proposal comes from the Government Finance Officers Association, a national lobby group for the people who run city budgets, and it suggests a radical overhaul of the way we fund local governments, a rethink that could reduce inequality, help balance municipal budgets, and create better and more fair regional economies.

The “rethinking revenue” project is necessary, the GFOA task force writes, “because local government revenues have not remained aligned with modern economic realities.”

Consider: most services — beauty salon appointments, home improvements, financial services and so on — aren’t taxed, even though our economy is increasingly tilted toward consumption of services rather than goods. It wasn’t until 2018 that sales taxes could be uniformly applied to online purchases, even though e-commerce now accounts for roughly 19% of all sales in the country, according to eMarketer.

Fuel taxes haven’t kept up with the increasing fuel efficiency of cars, let alone the ongoing transition to electric vehicles

DRIV,

And as MarketWatch has reported, cable television franchises don’t reflect the “cut the cord” phenomena of consumers embracing streaming services like Netflix

NFLX,

and Hulu.

In many cases, the way communities raise their revenue doesn’t line up well with existing regional economic structures. For example, in an area dependent on local sales taxes, the city that has the regional shopping center may get most of the pot, paid by people from other cities who shop there. Or there may be cities where many commuters go to work every day but pay little in taxes to support public services there. MarketWatch has reported on such a situation in Lansing, Mich.

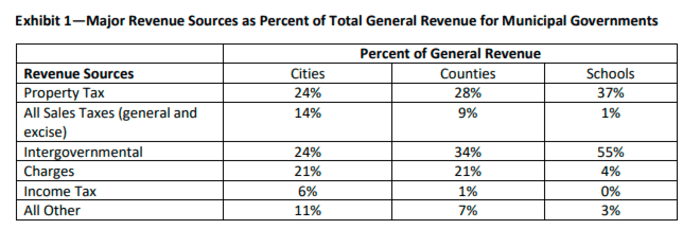

Source: GFOA, Urban Institute, Census Bureau

Why does this all matter?

First, there’s a large and growing backlog of things government should be investing in but can’t, most notably infrastructure, public health and education systems, preparations for climate change, and much more.

What’s more, local governments are increasingly vulnerable to economic downturns. It’s just when the economy turns south that citizens tend to need more public services, so government revenues should run counter to the business cycle as much as possible. Property taxes have historically helped in that sense: they move with a long lag, since it takes time for the downturn to show up in housing prices, and then assessments, and finally in tax collections.

But politicians and citizens have capped the amount of money that can be raised from property taxes, meaning governments have less to rely on than in the past.

“Between 1977 and 2017, property taxes went from 31% to 26% of total local revenues,” the report says. “Some of the revenues that have replaced it, like sales taxes, hotel taxes, or income taxes, are much more vulnerable to the economy. An ideal revenue system would provide steadier resources so that local governments have enough resources available during downturns but without overtaxing constituents at any time either.”

MarketWatch has also reported on another behind-the-times revenue raiser that figures prominently in the GFOA report: predatory fines and fees. “Overuse of fees and fines can lead to unfair and counterproductive outcomes for citizens,” the report says. “There have been documented cases where local governments spend more money enforcing delinquent court fees and fines than they collect.”

The fines and fees issue is perhaps the starkest example of inequity in government revenues, but it’s not the only one. As the GFOA report puts it, it’s often the case that residents paying a particular tax aren’t the ones who can afford it, or the ones who benefit from the public services funded by those taxes. In most cases, that disproportionately burdens lower-income residents, who spend more of their income on taxable goods than do higher-income people.

“The sources of revenue a local government uses to fund itself should reflect the bedrock value of democratic systems of government: fair and equal treatment,” the report adds.

“However, the current unfairness in the local government revenue system is not consistent with that value. Bringing our systems of local government in line with this fundamental value and creating a fairer tax and fee system is more important than ever with declining citizen trust in government.”

What’s to be done about it?

The task force that wrote the GFOA report summarized here intends to come up with proposals, it says, noting that it might be a tall order.

Local governments are often constrained by their state’s taxing rules — and even if it’s legal to impose new or different tax structures, the local residents may not be in favor, or the local economy may not support it.

“A rethought revenue system should provide all communities with revenue options responsive to local economies and that keep up with the cost of public services,” the report concludes. The GFOA project “can provide the needed flexibility for local government, while maintaining accountability for how much revenue is raised and how it is used.”