This post was originally published on this site

When the city of Falls Church, Virginia, receives the $18 million it’s been allotted under the American Rescue Plan (ARPA) stimulus legislation, the money will be “most definitely helpful,” according to Cindy Mester, its deputy city manager.

“We have more requests than funds,” she says.

After a months-long decision-making process with input from the community, city council and city staff, Falls Church has an outline of a spending plan. And even as Congress gets set to try once again to pass a massive infrastructure spending bill, the city has already committed to spending 39% of its $18 million on capital projects, including storm water improvements and affordable housing.

“We know what we have with ARPA, and we don’t know what any infrastructure bill will look like and when it might come,” Mester told MarketWatch. “We’re not waiting for the unknowns to come out of Congress.”

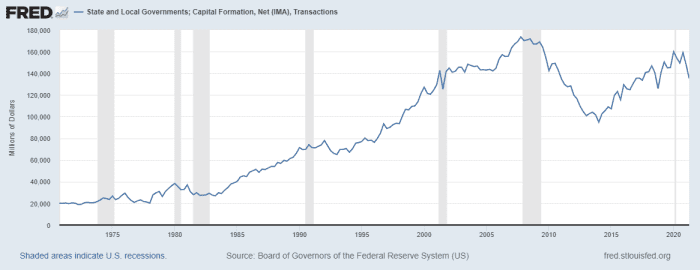

Across the country, many municipalities are making the same calculations. The needs are great, especially after a decade of stagnant capital spending and maintenance deferred after the Great Recession. The ARPA money is here now, and many communities recognize that its intent — tackling systemic issues and recovering from the COVID crisis equitably — aligns with long-term big-ticket projects like bridging the digital divide and making eco-friendly upgrades. And perhaps most importantly, no one wants to wait for Washington to get its act together.

“When you think about Congress delaying the vote on the debt ceiling (and other legislation), this is local governments throwing up their hands and saying, we don’t have time to waste,” said Emily Swenson Brock, federal director for the national Government Finance Officers Association.

There’s no data to help determine how much of the $65 billion of ARPA money going to localities is being allocated to infrastructure. Municipalities won’t start to report on its uses for several months. Many haven’t finalized plans yet, and it’s possible many of the initial plans might change midstream: the funds are to be distributed in two tranches, one this year and another in 2022.

But Brock, who speaks daily to community finance managers from around the country, says that in her experience, “the majority of recipients are using at least a portion of their proceeds on infrastructure.”

Oklahoma City Assistant Finance Director Angela Pierce calls the ARPA money “once in a lifetime transformational. It keeps me up at night, thinking, how can we be doing the best we can with what we’ve been given.”

The city will receive $122.5 million, an amount equal to one-quarter of its general fund budget of $496.4 million. Finance department staff have asked for proposals for infrastructure projects to be funded out of $78 million of the ARPA funds, and have already tallied $481 million in requests, Pierce said in an interview.

“One of the biggest hamstrings we have is the maintenance we deferred in the past. It’s a quick budget tool in the moment but it’s kicking the can down the road,” she said.

Now, the city wants to modernize its IT department, build a new maintenance facility for public buses, build a coliseum at the city fairgrounds, make HVAC upgrades to existing buildings, add a new police storage facility, and chip away at a “big housing initiative” to help address the city’s homeless population — just to name a few.

In contrast, the city of Chaska, Minnesota, has identified one single project for its allotted $2.8 million.

After a stretch of growth, with more anticipated, the city wanted to make improvements to its water system, including bringing an underperforming well into service and adding a second treatment plant, as part of a broader capital improvement plan.

“If we didn’t have this plan in place, we’d have some concerns about ability to deliver water,” said Noel Graczyk, the city’s Administrative Services Director.

For Chaska, one bonus of using the ARPA funds for capital projects is the ability to avoid issuing debt to pay for it. “We anticipate that rather than financing the entire project, (expected to cost $7-8 million) we’ll use the ARPA money to front-end the construction” Graczyk said.

Pierce, of Oklahoma City, says that not having to issue bonds may be just as transformational as the funds themselves. “That’s something you can’t reach out and touch, that future budget flexibility, not bonding those projects out 20, 30 years into the future.” She points to not just the cost of debt service, but underwriting fees and staff hours on things like continuing disclosure.

Related: U.S. local government hiring picks up after touching two-decade low

And in Falls Church, Mester noted that projects funded by cash rather than bonds may be able to be completed more quickly.

Still, everyone who spoke with MarketWatch acknowledged the uncomfortable reality of using one-time stimulus money for big projects that require ongoing maintenance.

Brock says that the municipalities she hears from are allocating funds to projects that have long been identified as needs within a long-term capital spending plan. Most “already have their upkeep built in,” she said.

That’s one key difference between the current moment and the aftermath of the Great Recession. Many public finance observers believe that the tepid recovery from that downturn was exacerbated by the reluctance — or inability — of states and localities to spend.

State and local government spending on infrastructure still isn’t back to the 2007 peak. Source: St. Louis Fed, Federal Reserve

Falls Church is thinking more holistically about its budget in this cycle, Mester said. Spending ARPA funds on stormwater upgrades doesn’t help the general fund, since water services are a separate budget — but the ability to reduce water rates helps the same households that are paying taxes to the general fund, she noted.

“We really want to message this as investment in the community, not just a blank check,” Mester said.

Read next: Climate risk is hitting home for state and local governments