This post was originally published on this site

Investors should monitor whether ongoing competition between the world’s two largest economies and its two greatest polluters — China and the U.S. — will be constructive or destructive in their efforts to slow global warming, as well as the health of portfolios tied to the environmental efforts of these giants.

That tension is only likely to intensify as they and other economic powerhouses submit to firmer climate-change goals — if all goes to plan for the U.N. — as part of the ambitious global summit in Glasgow running Oct. 31-Nov. 12, known as the U.N.’s Conference of Parties, or COP26.

Related: What is COP26 and when does this ‘ambitious’ global climate change event begin?

“A healthy competitive dialogue [between the U.S. and China] will lead to a ramp up in clean energy investments and advances in nascent technologies, for example, green steel. A negative outcome would inhibit capital flows for low-carbon solutions

LCTU,

” said Jeffries analysts led by Aniket Shah, global head of ESG research.

“Investors should monitor any new commitments signaling renewed cooperation or, at a minimum, any shifts in sentiment,” the team said in a research note. “Both countries enter COP26 with difficult positions from a domestic political economy perspective.”

Read: ‘A leadership gap’: U.N. says U.S. and major nations’ emissions pledges backload much of the effort

Awaiting details

China, the world’s top emitter of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses that cause global warming, formally submitted its goals to the Glasgow conference this past week. But, said analysts, that report offered no significant new goals for reducing climate-changing emissions, especially over the short run. The announcement included targets previously delivered in speeches by President Xi Jinping, who will not attend the Glasgow summit in person but will deliver remarks by video.

China says it aims to reach peak emissions of carbon dioxide, produced mainly through burning coal, oil

WBS00,

and natural gas

NG00,

for transportation, electric power and manufacturing, “before 2030.” The country shoots for net-zero emissions of CO2 before 2060, a decade beyond the U.S., the U.K., and the European Union’s net-zero pledges.

Climate experts say key questions about China’s plans remain unanswered.

“The document gives no answers on the major open questions about the country’s emissions,” Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air in Helsinki, told the Associated Press. “At what level will emissions peak and how fast should they fall after the peak?”

China’s seriousness in cutting emissions much ahead of the 2060 self-imposed net-zero deadline marks a significant unknown, but an important piece of its overall policy.

“For China to get on a pathway to reach its 2060 carbon neutrality goal it is critical for the country to further strengthen its new near-term targets and put in place measures to reach them,” said Helen Mountford, vice president, climate and economics, with the World Resources Institute.

Proving it can hit such goals would mark a position of strength for the country, and its investors.

“China has strong economic and social incentives to adopt ambitious climate policies,” Mountford said. “WRI research shows that bold climate action by China could generate savings of $530 billion in fuel, operation, and maintenance costs over 30 years. Ambitious climate action would also save China nearly 1.9 million lives and generate roughly $1 trillion in net economic and social benefits in 2050.”

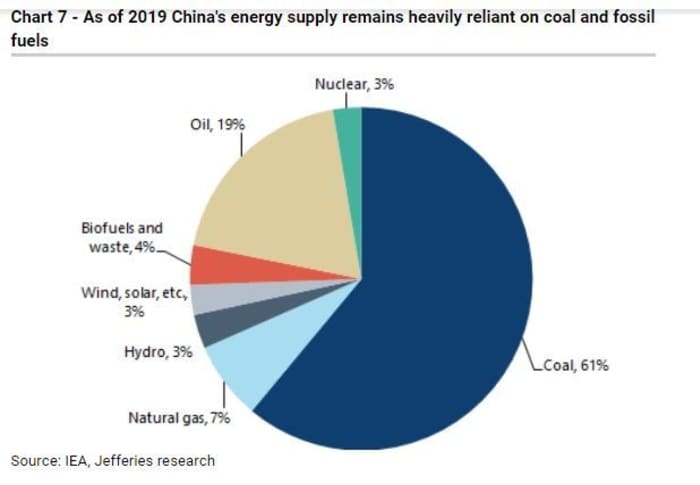

China is expected to face pushback from its economic rivals as it ramps up coal production, one of the “dirtiest” contributors to global warming.

China is currently swept up in an energy crisis hitting Asia and Europe that has choked off natural gas distribution. With winter approaching, a tight natural gas market has resulted in Beijing calling for an expansion in coal production, an already significant portion of their energy mix. This is a headwind for the country’s goal of eventual carbon neutrality.

That impact is also seen in markets. The resurgence in demand for traditional fuel leaves the iShares Global Clean Energy ETF

ICLN,

down nearly 12% year to date.

And in the U.S.

President Joe Biden said he’ll enact policies to put the country on a path to at least halve its emissions by 2030 and hit net zero two decades later.

But the administration has not gotten as much help from Congress toward this effort as it set out to achieve at the beginning of Biden’s first term.

A modified, meaning smaller, framework for spending was advanced this week, and remains under consideration in Congress. It includes $555 billion in lower-emitting clean-energy programs by way of tax incentives and other approaches, with climate-change efforts taking up the biggest slice of this spending proposal.

With executive powers, Biden has returned stronger authority to the Environmental Protection Agency after the Trump administration’s regulation-lite approach and directed more financial-market climate-change coordination at the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Treasury and across banking and insurance regulators. And he and Climate Envoy John Kerry have said private-sector responses to climate change will be crucial to the effort, a tack more Republicans and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce favor.

Read: Democrats compare oil companies’ climate change response to tobacco-cancer denial

But the U.S., the world’s second-largest polluter behind China, and followed by India in third place, has some ground to make up on the global stage.

“Given their withdrawal [a Trump administration move] and subsequent re-entry into the Paris Climate Agreement, we see the U.S. as being somewhat on the back foot in recent years with regard to climate goals,” said Jeffries’ Shah.

It was at Paris six years ago that governments set the voluntary goal to keep the global temperature from rising no more than 2 degrees Celsius and ideally no more than 1.5 degrees due to climate change. According to U.N., the Earth’s temperature has already gone up an estimated 1.1 degrees Celsius since then.

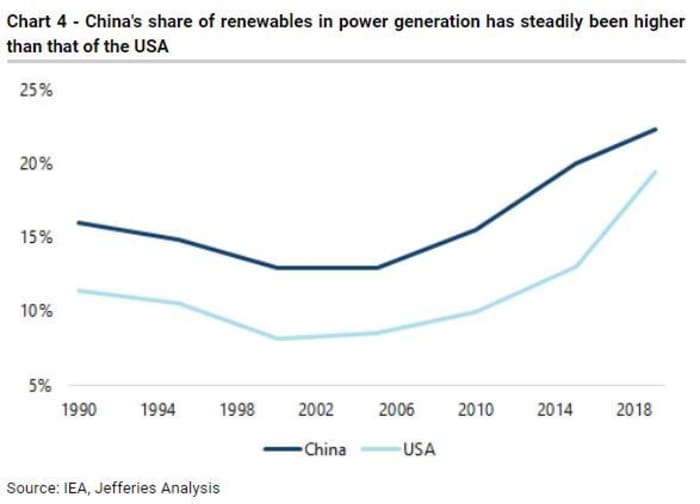

“Although the new [Biden] administration has recently taken steps to scale up its climate ambition, differences in the political apparatuses between the two countries has led China to enacting green policies and developing low carbon solutions at a faster and more wide-reaching pace,” the Jeffries analyst said.

He said this is most apparent in China’s dominance in renewable electricity generation and, in particular, solar-powered production.

China, the analysts said, is also topping the U.S., in the way it uses the rest of the world to expand its green efforts. That includes, as part of its Belt & Road initiative, 30 nuclear reactors

NLR,

around the world by 2030. And a Chinese operator has already opened Latin America’s largest solar plant

TAN,

in Argentina.

Political risk

As for the U.S. political climate, little cooperation with China takes place without other trade, labor and security issues taken into account. Those concerns remain a major sticking point for Republicans.

And, many observers of the emissions-pledging process don’t want the U.S. to shoulder extra responsibility.

“The U.S. could hit net-zero, for the sake of argument, tomorrow, and that is still only 11% of global emissions. We care, too, about the other 89%,” said Heather Reams, executive director of U.S.-based, center-right Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions (CRES). “What is China doing? What is India doing?”

The Jeffries analysts said bullish investors on clean energy and the transformation of the industrials and construction sectors toward greener processes would be encouraged if China and the U.S. start to show cooperation on intellectual property around the nascent technologies — again, green steel — needed for a net-zero economy.

And both would be better served to help emerging and frontier markets to increase the labor skills and infrastructure to manufacturer this technology, the analysts said.

Stubborn competition between the two “would limit the spread of green technologies and inhibit capital flows for low-carbon solutions. The market for clean technology would become increasingly fragmented, inevitably spilling over to other sectors of the global economy,” Shah said.