This post was originally published on this site

For more than three years, Patrick Rodriguez has worked at a Chipotle restaurant at the northern tip of Manhattan, a vital food lifeline during the pandemic for the nurses and doctors who work a block away at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

“Last year, we were heroes [serving healthcare workers],” Rodriguez said Wednesday. “And now, look at us. We’re striking.”

Rodriguez and several other Chipotle workers did not show up for their shifts Wednesday morning, becoming the latest group of fast-food workers who have gone on strike or held labor-related actions around the nation in the past several months. The Chipotle location’s workers say they need to call attention to their hours being cut — and that when they are at their jobs, they are overworked and overwhelmed with orders.

In the age of the iPhone, DoorDash and a pandemic, online orders have exploded in an overwhelming mix of takeout and delivery, resulting in a lucrative additional revenue source for fast-food restaurants—and a lot of stressed-out workers and frustrated customers.

Last week, Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc.

CMG,

Chief Executive Brian Niccol said on the company’s earnings call that the company has reached nearly $2.7 billion in online revenue so far this year, close to its total $2.8 billion in online sales all of last year.

For Chipotle workers who assemble burritos and taco bowls in front of customers at restaurants, as well as for customers who order online, that has meant increasingly tough conditions. MarketWatch spoke with current and former workers in five states and reviewed hundreds of Chipotle worker complaints on Reddit, documenting food and supply shortages, inadequate space at stores, problems with staffing, and unrealistic online customer order times.

Through the third quarter, the company’s overall revenue is up 27% since the same period last year, while its employee count has climbed just 8% higher. In other words, Chipotle is churning out a lot more burritos, but the number of people making them has not risen anywhere near as much.

As a cashier, Rodriguez said the pace can be dizzying, especially because online orders have become part of a crushing new reality.

“It’s like being ripped into two,” Rodriguez said. Because his location is so understaffed, he said there’s a person on the digital-make line, which handles online orders, while he often is solo on the main line that serves in-store customers. That means preparing orders and handling the cash register by himself.

Yet his hours have been cut to about 15 to 17 hours a week from about 32 hours a week, because he said the location’s general manager is trying to save money.

Chipotle workers are not unionized, but Rodriguez and his colleagues got support from the Service Employees International Union for Wednesday’s walkout. In a news release, the union noted that Chipotle is already facing a lawsuit filed by New York City earlier this year, accusing it of violating the Fair Workweek Law, which requires that employers give workers a good faith estimate of their regular schedule as well as a two-week notice of their set schedule.

Manny Pastreich, secretary treasurer for SEIU Local 32BJ in New York City, said workers contact the union not just over wages but issues like workload and not being treated with respect by their employers. The rise of delivery that was sparked by the pandemic has changed the fast-food industry, he said.

“It’s just become part of the way people are ordering food. And the staffing hasn’t matched the increased workload,” Pastreich said.

‘The orders wouldn’t stop’

There was a point at the beginning of the pandemic last year when no one was going out to eat, and Chipotle employee Albert Morales said he was “thinking no one would have a job.”

Then, “boom, the next day the orders wouldn’t stop,” said the service manager of a Chipotle in the Bronx, which he says is the most popular Chipotle location in the northern borough of New York City. During one of the busiest times in the past year, his location ran out of paper the orders were being printed on so they had to borrow some from the Starbucks next door.

But some of the issues Morales has had to deal with have not been so easy to resolve. Morales recalls a day when his location was closed to in-store dining and was fulfilling only online orders. A backup with about 30 people waiting outside resulted, and one customer was getting increasingly agitated after claiming he had been waiting for his food for an hour. The customer picked up a chair and threw it, leaving a mark on one of the windows.

Morales called the police twice, but nobody came until he and his employees flagged down a couple of officers they saw driving by. Those officers eventually calmed the man down, who by then had been raging for 15 minutes.

“He was yelling and cursing,” Morales said. “He wanted to fight with me and the employees, and wanted to beat up our security guard.”

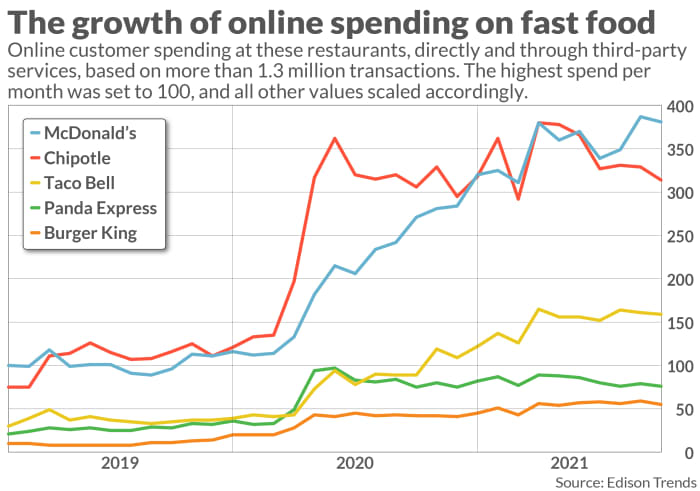

A look at more than 1.3 million transactions at Chipotle, McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Panda Express and Burger King from January 2020 to September 2021 shows huge spikes in online spending during the beginning of the pandemic last year, according to an analysis by Edison Trends. Chipotle saw a surge of 172% in online spending from January to May last year. That spending has continued to increase for the most part since then, with McDonald’s and Chipotle seeing the most online spending by their customers, respectively.

Laurie Schalow, chief corporate affairs officer at Chipotle, downplayed worker concerns. “We were seeing increased staffing needs, however, Chipotle is incredibly fortunate to have a steady influx of applicants due to its strong values, leading benefits and mission to cultivate a better world,” she said in an email to MarketWatch.

“In a few minor instances, there have been challenges with available labor so we made adjustments in these restaurants to temporarily accommodate the needs of the business,” she added. Those adjustments included changing hours of operations or having stores switch to digital-only orders during certain times. Chipotle did not quickly respond to a request for comment about Wednesday’s employee walkout at one of its Manhattan locations.

Niccol, Chipotle’s chief, sent mixed messages about the worker shortages during the company’s earnings call. On one hand, he said “We do a good job of winning that hiring competition.” On the other hand, he said “I know we’re missing sales because not all [restaurants] are fully staffed.”

Some workers couldn’t take it anymore

Andrew Luettgen quit working at a Chipotle in Bloomington, Ind., in March. He said the store “kept losing people left and right,” and he was set to graduate from college anyway. The staffing shortage at his store meant he would frequently get texts from managers, asking him to work extra shifts.

“Sometimes I had already worked 40 hours,” he said. “Sometimes I just needed time to rest.”

Though Luettgen had not meant to leave his job until May, he made a “spur of the moment decision” to quit after he got some pushback for standing up for his colleagues making food for digital orders. Luettgen felt the general manager unfairly got upset at them during one of the store’s busy times.

Luettgen recalled another time the Indiana University location where he worked became so “overwhelmed that everything cascaded.” The store ended up being shut down to walk-in customers at 7 p.m. so the workers could focus on the online orders until closing time.

“People would just stare at us, angry,” he said. “Orders were coming in faster than they could be made. We would frequently see orders of 75, 80, 90 items within a 15-minute time span.”

Workers have also had negative experiences with DoorDash and other delivery people, whose earnings depend on making as many deliveries as possible.

“They were always very stressed and trying to do mental math: ‘Can I do another order in the time it will take to get this Chipotle order?’ ” says Luettgen.

The promise times—when online customers are told their orders will be ready—can be unrealistic, Chipotle workers told MarketWatch.

“We get several orders within each 10-minute interval and we often have people coming in saying, ‘the app said my order was ready’ then getting annoyed when they have to wait for their food,” said Pranav Iyer, who works at a Chipotle in Davie, Fla. “Even when the order is placed at 11:57 a.m., the promise time will still be listed at 12 p.m.”

Mark Kalinowski, chief executive of Kalinowski Equity Research, which focuses on the restaurant industry, said “fast-food casual was challenging even pre-pandemic. These are not easy jobs. Now you have safety concerns.” He added that combined with an increased workload, “there are some people who just don’t want to work in this type of environment.”

A former employee, who did quit in September after working for more than a year at a Chipotle store in Concord, N.C., said the job became particularly stressful when the store ran out of ingredients and supplies, which happened “all the time.”

“Onlines could be particularly very brutal some days,” the former employee said, adding he did not want to give his name. “Some days we would shut down and take only onlines.”

There are also ingredient shortages at the Chipotle restaurant in Vallejo, Calif., says an employee who has worked at the location for a little over a month.

“We’re consistently dodging what we don’t have,” said the employee, who did not want to reveal his name because he still works for the company. “We’re told if we have no steak, give them chicken.” That kind of substitution has made some customers angry, and he said that at his store, “managers will step in to make sure workers don’t get yelled at.”

The employee said online seems to be the priority. “Sometimes we’ll save our guacamole for online, or when they run out of food in the back [where the online orders are made], they take it from the front.”

Schalow, the Chipotle executive, said there is no network-wide disruption to the company’s supply chains. She said ingredient shortages are “isolated instances,” and restaurants are supposed to let the corporate office know so the ingredients can be removed from the app and website. But workers said it can sometimes take a couple of hours for the app and website to reflect those changes, meaning that in the meantime, customers could be ordering ingredients a location doesn’t have.

As workers struggle with being asked to do more in less time, Niccol, the CEO, marveled during the company’s earnings call at what he said was an improvement in how long it takes for online orders to be fulfilled by Chipotle employees. “The time from your order to actually your food being ready is now less than 10 minutes in our business, so we’ve gotten even faster at this space to make it even more convenient,” he said, adding that “a couple quarters ago that was in the 12-minute range.”

Schalow said the company holds listening sessions with employees, and offers an anonymous number for them to share their concerns.

But Iyer, the Chipotle worker in Davie, Fla., said, “Chipotle says they always accept employee feedback, and I assume customers complain when their orders are late, but nothing ever gets done so nothing indicates they’re listening, unfortunately.”

Another example of tech changing an industry

Brendan Witcher, a Forrester analyst for digital business strategy, said the fast-food industry is having a moment like retail did a few years ago, when stores had to rethink their models and processes as online sales increased.

“Associates who were normally on the sales floor and restocking suddenly had to pick and pack orders,” Witcher said. “Just as stores were never designed to be pick locations, neither are these places.”

“Every single retailer and QSR [quick service restaurant] out there always launches these things too soon,” Witcher said, adding that there are bound to be growing pains. “I’ve never seen a retailer or QSR flawlessly execute omni-channel.”

Yet companies like Chipotle are doubling down and moving ahead with plans to take advantage of their momentum.

“The company continues to innovate its restaurant layout and design to accommodate its growing digital business with items like pickup shelves, walk-up windows, and Chipotlanes,” Schalow said.

Chipotle is including Chipotlanes, or drive-throughs where customers can pick up their digital orders, at 70% of the 200 locations it’s opening this year, she added. And the company has opened a digital-only location in Highland Falls, N.Y., which Schalow said will serve as a prototype for future locations.

Despite the challenging conditions they describe, some Chipotle workers are choosing to stay because of what they say is competitive pay or perks offered by the company.

After signs at one of its East Coast location about workers being overworked and underpaid went viral, Chipotle announced in May that it was raising its workers’ pay to an average $15 an hour, with starting wages from $11 to $18 an hour. The company introduced tuition benefits in 2019, and now offers 100% tuition coverage for some degrees and up to $5,250 a year for others. In addition, employees can get a free meal during their shifts.

Iyer, who’s majoring in public health, said he plans to apply for tuition assistance, which he expects will help cover, along with scholarships, his full tuition. “It’s one of the main reasons I still work there aside from free food,” he said.

Morales, who has been with the company for four years, said the $22 an hour he makes at Chipotle beats just about anywhere else he can work right now. He also is going to college and has taken advantage of tuition assistance and plans to do so again.

“It’s not easy but I’ve come to accept what I need to do,” he said.

Read on: What minimum-wage increases did to McDonald’s restaurants — and their employees

This story has been updated with the correct spelling of Forrester analyst Brendan Witcher’s name.