This post was originally published on this site

“When the well is dry, we know the worth of water,” Benjamin Franklin wrote in Poor Richard’s Almanac.

Franklin likely meant it metaphorically, but in much of the western United States, now enduring “extreme drought” conditions yet again, it may be felt literally. As the wells remain dry, and as the climate continues to change in ways that upend our lives and our expectations, American communities are increasingly looking for ways to recycle our most precious commodity.

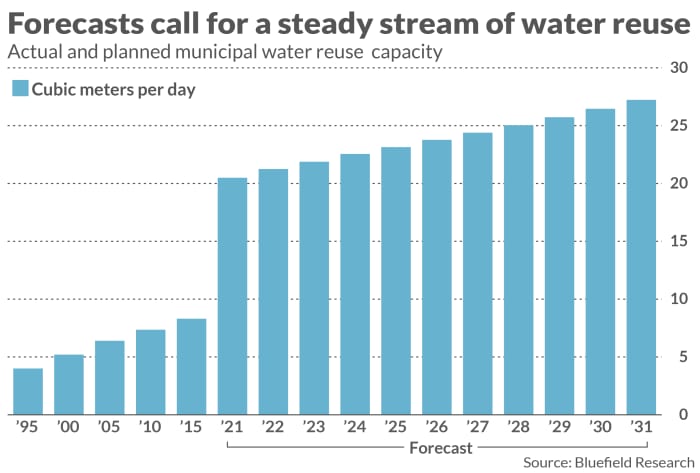

Data from water market intelligence firm Bluefield Research shows 635 planned “water reuse” projects, and an estimated 300 in operation, around the country. That’s not just in places socked by the drought or in the desert Southwest, but Hawaii, Florida, Iowa, and beyond. Gaining even just a bit more certainty about access to water seems to offset any “ick factor” people may have about a process sometimes referred to as “toilet to tap.”

“We’re looking at factors that will be increasingly important beyond just drought and scarcity, things like resiliency for storms and floods, and redundancy for critical infrastructure,” said Greg Goodwin, a research consultant with Bluefield.

“When the 100-year storm becomes the 5-year or 10-year storm and infrastructure isn’t built to withstand a Hurricane Sandy every few years, lots of places will be thinking about this. Every region is going to have some level of climate disruption.”

See: Climate risk is hitting home for state and local governments

“Reuse” and “reclamation” are broad terms that can mean lots of different approaches to recycling water. Salt water can be desalinated to make it usable, and wastewater can be purified to make it usable — even potable — for humans.

Most experts in the field stress that the choices a community or utility makes depend heavily on location. Is there a natural water source, like an aquifer, nearby into which mostly-purified water can be returned? Is the community near salt water for desalination? Is it part of a larger watershed which could reimburse it for upfront costs for building a reuse system, if that helps reduce regional usage in the future?

For now, means that most policies are developed at the state level, Goodwin told MarketWatch, with not much national leadership on the subject. Still, the federal government is investing heavily in funding such projects, noted Peter Grevatt, CEO of The Water Research Foundation, a Denver-based research collaborative.

Much of that funding, in the form of both grants and loans, comes from the Environmental Protection Agency, including a relatively new program called WIFIA, for Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act, as well as state revolving loan funds. Some additional funding is considered in President Joe Biden’s infrastructure proposal, Grevatt said, marking what he calls “an ongoing commitment to water reuse” at the federal level.

The city of Oceanside, California, tapped into growth in interest and financing when it launched a potable reuse project called Pure Water in early 2020. Construction is expected to conclude in late 2021 and cost about $82 million, but reap big benefits.

After the last drought, Oceanside’s city council asked its Water Utilities Department to aim to have 50% of the city’s water originate locally, said Lindsay Leahy, principal engineer of the utility. At the time, 90% of the city’s water was imported, while 10% came from a local aquifer.

Oceanside is “at the bottom of California,” Leahy said in an interview, “at the end of the pipeline. Whenever water conservation efforts go into effect, that impacts us greatly.”

The project will be financed from a hodgepodge of sources, including a WIFIA loan from the EPA, $30 million of bonds issued in 2020 at a rock-bottom interest rate, various other grants, and yearly reimbursements from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, of which San Diego County’s water authority is a member, for a period of 15 years.

“The main benefit is reliability,” Leahy said, not just in terms of being able to turn on the spigot and get water, but also to be able to depend on more consistent rates than mostly-imported water would bring. One bonus: more water reuse means less discharge into the ocean.

Pure Water Oceanside also benefitted from another, less tangible, but experts say critical, source of support: community buy-in.

“I think we can acknowledge that the source of the treated water being wastewater can be a concern for some folks,” Grevatt said. “It’s so important to make sure the local communities are engaged in conversations and a city thinking about a project like this take careful steps to talk about why it’s safe and protected. Where projects have really run into problems, it’s primarily been as a result of a lack of effective public communication.”

As Bluefield Research noted in an August 2020 presentation, the COVID pandemic “presents an additional ‘yuck factor’ obstacle.”

Oceanside worked hard to engage the community, Leahy said, but believes public acceptance has come a long way. “Honestly, the city and the community totally embraced the project. It was overwhelming support from everyone.”

There’s one other caveat to reusing water, and it may have particular resonance for communities conscious of climate change. Some reuse processes can be big energy hogs. As Bluefield’s Goodwin put it, “There probably is some level of tradeoff there. You’re definitely going to be raising operational coasts and energy is one component. The overall calculation is that the value of the water that’s offset is greater than the worry about carbon footprint.”

Still, as Oceanside’s Leahy told MarketWatch, the experience of the “last few droughts” went a long way to convincing residents of the need for an unorthodox form of water delivery. As climate change effects continue to increase, communities across the country will likely have to consider tradeoffs they never anticipated.