This post was originally published on this site

What investing lessons can be learned from Harvard University’s failure to beat the S&P 500

SPX,

in its latest reporting period?

It’s a timely question, given the university’s report of its endowment’s investment return in the fiscal year that ended Jun. 30. That return was a gain of 33.6% — 7.3 percentage points lower than the S&P 500’s total return.

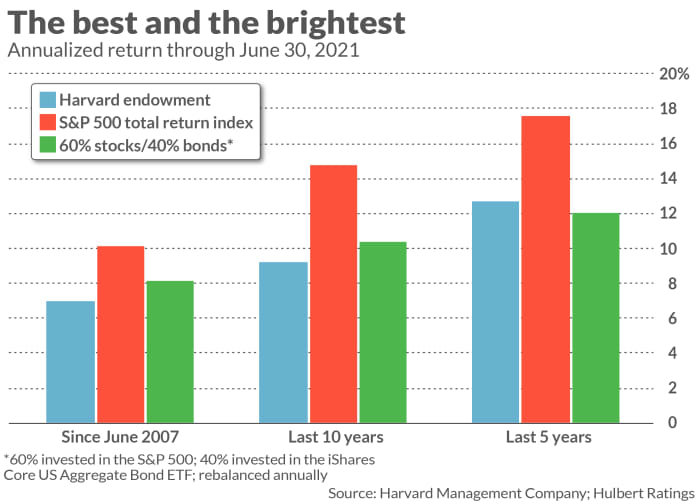

Lagging the stock market is nothing new for Harvard; the endowment has done so more often than not in recent years. Cumulatively over the past decade it has lagged the S&P 500 by 5.6 annualized percentage points. (See chart, below.) It has also lagged over the past 14 years, a period chosen to include the 2007-2009 bear market and the Great Financial Crisis.

You may see these numbers as putting Harvard’s investment abilities in a poor light. But I suggest you suspend judgment long enough to entertain a number of nuanced investment lessons that can be drawn.

Was being conservative a mistake?

For starters, Harvard’s endowment may be significantly more conservative than many of its peers. That at least is the argument made by the Harvard Management Company, the firm that manages the endowment. In response to an email seeking comment, the firm’s director of communications sent me a report acknowledging that “a meaningfully higher level of portfolio risk would have increased [the endowment’s] returns dramatically.”

How dramatically? Consider that Duke University reported a 56% return for the June 30 fiscal year. Washington University in St. Louis reported a 65% return.

Read: The radical idea on college campuses: Using endowments to help students and staff in crisis

Insofar as Harvard’s conservative posture is the source of its endowment’s lackluster returns, then the lesson we should draw is not that they failed to beat the market. Instead, the “mistake” they made was being conservative in the first place.

But is that a mistake? Just because the risk they perceived hasn’t materialized doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

Lawrence Tint is at least partially sympathetic to Harvard’s explanation that its conservative posture is largely to blame for its lackluster returns. Tint is the former U.S. CEO of BGI, the organization that created iShares (now part of Blackrock). Over the years he has consulted to a number of nonprofit institutions’ endowments.

In an interview, Tint told me that much depends on Harvard’s underlying motivations in being conservative over the past year. On the one hand, he would be less sympathetic to Harvard’s argument to the extent they’ve had a history of engaging in market timing. Market timing is notoriously difficult, even for the best and brightest investment minds that Harvard assembled to help manage the endowment. If they nevertheless had tried to time the market when reducing their endowment’s risk level, it’s entirely legitimate to call them to task for failing to anticipate the bull market of recent years

On the other hand, Tint said, he would be more sympathetic to Harvard’s argument to the extent its conservatism derived from the belief that, with such a large endowment, there’s no need to be particularly aggressive. Harvard is in a far more solid financial position than less well-off universities and colleges, which have little choice but to incur more risk if their endowments are to grow large enough to fund their educational missions. Harvard’s endowment, in contrast, is now so large — $53 billion — the argument could be made that it would be imprudent to incur more risk unless there was a real need to do so.

Harvard Management Company, in the report sent in response to a request for comment, argues that its motivation was this second, more sympathetic one. The conservative posture resulted from an extensive internal discussion “integrating Harvard’s financial position, its need for budgetary stability, and its ability to handle more risk… Ultimately, we all seek the appropriate risk level for Harvard, which might well be different from that of other university endowments.”

Tint says this doesn’t necessarily resolve the issue of Harvard’s motivation, since it would be unusual for Harvard — or anyone, for that matter — to admit they had made a significant market-timing mistake.

Regardless, the investment implication for the rest of us is clear: Pick whatever risk level is appropriate for your financial situation, and then stick with it through thick and thin. You should resist the temptation to increase or decrease your risk level because of short-term market timing judgments, because almost all who do so end up with less than they would have with a strategy that incurs a constant risk level over time.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: This toxic combination is part of the reason Americans are so unprepared for retirement