This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

Many astronauts’ careers peak when they make it to space. Not so for Nicole Stott, who says she’s on her “next mission.” Now 58, Stott has parlayed her broad array of interests into an impressive post-NASA second act. Not that she had anything to prove.

In 2009, the engineer spent 104 days as a mission specialist aboard the International Space Station, even finding time to do the first painting in space, a watercolor that now resides in The Smithsonian.

Since retiring from NASA in 2016, she’s been active in foundation work, promoting science careers for girls and young women and exploring the intersection of art and science.

Now, Stott harnesses her diverse passions in her first book, “Back to Earth: What Life in Space Taught Me About Our Home Planet — and Our Mission To Protect It.”

Next Avenue caught up with her via Zoom

ZM,

from her home in St. Petersburg, Fla. Her responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Next Avenue: You’ve found inspiration in ‘Earthrise,’ a 1968 photo made famous by astronaut Bill Anders when he captured the distant Earth rising above the Moon’s surface from Apollo 8. What is it about that moment that people find so revelatory?

Nicole Stott: In the simplest way, I think it was a reality check, right? It was the first time really and truly with human eyes, another human sharing this incredible, extraordinary experience they were having, of seeing our home in space…and just the reality of who and where we all are together, you know, the undeniable reality of it.

And I think that was pretty revelatory, pretty stunning in the beauty of it, for sure. But I think, stunning in the reality of it as well.

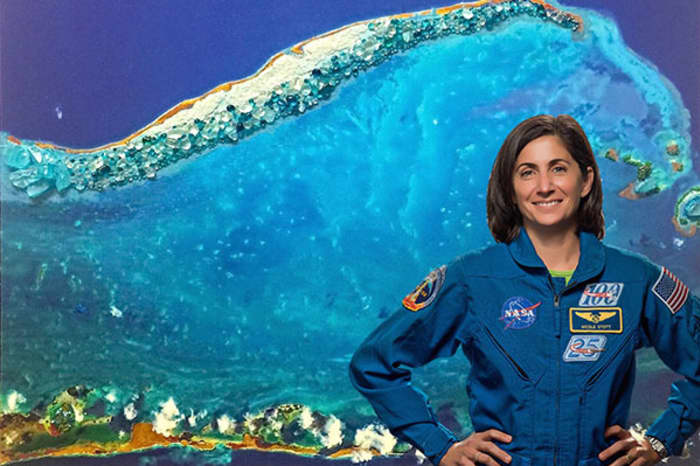

Nicole Stott in 2018

NASA Kennedy Space Center

And that reality, you write, is that we’re all ‘Earthlings;’ that we live on a planet and — just as when you’re aboard a tiny life-support bubble in space — that we should ‘live like crew, not like a passenger’ here on our home planet. What’s the message there?

It’s sad to me in some way that it took me going to space and looking out a window back at our home planet to realize the impact of that statement — that we live on a planet and that we’re all Earthlings and that the only border that matters is that thin blue line of atmosphere. I think we should feel that revelation, that reality check as a call to action.

You know, we build this mechanical life support system in space to mimic as best we can, what earth does for us naturally. Every day on the space station, we are acutely aware of how much CO2 is in our atmosphere, of how much clean drinking water we have, of the integrity of our thin metal hull, of the health and well-being of all of our crew mates, regardless of which country they’re from.

And when we do those things together, when we’re aware of them and we act on them, we actually can thrive in that place. You know, seven people on a space station or seven-plus billion on a planet.

See: Prince William to Bezos and other space billionaires: ‘Repair this planet, not find the next’

What do you think about this idea advanced by Elon Musk (the head of Tesla

TSLA,

and SpaceX) that the long-term survival of humans depends on us becoming an interplanetary species?

I think there’s truth in that. And I look at Mars as this other planet, that’s a steppingstone for it.

I would argue, any space exploration that we’re planning from here on out and the stuff we did before, that ultimately it’s all about improving life on Earth. The science that we’re doing, the international partnerships that are in place, all of these things are brought back to Earth with us.

Also read: William Shatner went to space, and had a life-altering experience: ‘Is that the way death is?’

You write about the ‘boldface checklist’ that was a key to problem-solving on the space station. Given the multiple environmental crises we face as ‘crew’ here on Spaceship Earth, including widespread climate breakdown, what’s our boldface checklist right now?

Yeah, well, I think first of all, it’s recognizing that there is a call to action: These are the things that we absolutely must do to put ourselves in a safe configuration. And I think that requires us both at a personal level and like, on a planetary community level, to raise our awareness to the kinds of critical things that are happening to our spaceship, and to realize that we all need to be doing those things that put us in a safe configuration.

You know, I don’t want my whole neighborhood going up in flames. And I don’t want the water that’s in my backyard to be toxic to me or to the life that depends on it. These are very simple things that require pretty complex solutions.

It seems oversimplified, but we have to get back to this basic understanding of what we all rely on to survive, that then puts us in a position to thrive.

I got the sense from your book that you feel like NASA has become a fairly level playing field for women. In a culture that tends to treat people over 50 as disposable or obsolete, what do you think the value is of NASA, for example, keeping the grizzled veterans around as active participants in the program?

Oh, I’ve seen it, you know, as a younger engineer and the appreciation of what you’re talking about. And now as perhaps one of the partially grizzled, you know what I love is that I still have people at NASA on different teams coming to me for participation, not to mention the companies outside that are looking at how we do this new space thing, too.

And now we were in this new place [with] —faster, better, cheaper new technology — which we all agree is wonderful. But to bring that [older] talent in, to have advantage of their time, I think is critical.

We brought in people that recovered Apollo capsules, that helped design the Apollo program, that kind of saw this transition from Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, all the way through and what we learned. We have that knowledge, these people are here and want to share it with us.

We should be looking at how you improve on what we already know, not take steps backwards, which way hatches open, wearing pressure suits when you’re launching into space, these kinds of things that seem like they’ve become the norm.

I think these people that have this firsthand knowledge, I’m guessing they’re begging to have their brains picked: ‘Let me just look at what you’re thinking about doing, I might see something there that you might not recognize, and here’s why it’s important.’

One of your art-meets-science projects is a collection of ‘space suits’ created by schoolkids. One of those suits will be on display at the upcoming U.N. climate conference in Glasgow. What’s the connection there and how critical do you think this conference will be in keeping a rein on global heating and climate breakdown?

I think it’s critical on a number of levels. You know, since [the 2015 Paris climate accord], a lot has been going on, and yet it seems like a lot hasn’t gone on. It’s another awareness check. It’s another one of these reality checks.

What I love — and I try to convey this in the book, because I think we all need this too — is that there is hope. That’s where I hope we’re at in this year, is this radical shift to implementing the boldface checklist on a planetary community scale and allows us to do all of the things we know we need to do both on an individual and an Earthling-wide level.

OK, we just have to know: how the heck — I almost said, ‘How on Earth…’ — do you paint with watercolors in microgravity?

Very carefully. A little bit like how you do everything in microgravity.

You’re not dipping your brush into a cup of water, ’cause we don’t have cups of water up there. So you squeeze a little ball of water out of your drink bag and you put the brush toward it and you watch as the ball of water wants to move over on the end of the brush and just kind of float around on it and the way the paint mixes with the water. And then you’ve got this floaty ball of colored water, and you gotta be really careful because if you move your brush too fast, that goes everywhere and becomes a bunch of little floaty balls…

It becomes a Jackson Pollock.

Yeah! And it’s funny because I wish I would have done a little bit of that — just, you know, let the microgravity do its thing and see what comes of it. And I did in some ways, because I discovered that if you actually tried to paint with the brush, touching the paper, the whole blob of colored water just went to the paper at once.

You might like: Attention Attenborough (and Trump), Greta Thunberg gets a BBC series

And I really think it’s one of those things that is allowing us to put the ‘human’ in human space flight, you know, to bring a watercolor kit to space or my friend, Karen [Nyberg] quilting on the Space Station and people writing poetry and playing music.

I mean, it’s been going on since the very beginning of space flight. And yeah, Jackson would have fun up there.

Craig Miller’s career in broadcasting and journalism spans more than 40 years, though since 2008, his focus has been on tracking climate science and policy. Miller launched and edited the award-winning Climate Watch multimedia initiative for KQED in San Francisco, where he remained a science editor until August of 2019. Prior to KQED, he spent two decades as a television reporter and documentary producer at major-market stations, as well as CNN and MSNBC. When he’s not working, his favorite spot is in his kayak on a scenic river or mountain lake.

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2021 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: