This post was originally published on this site

Sometimes a rising oil price is good for stocks, and sometimes it isn’t.

That earth-shattering insight is my response to those Wall Street analysts who are wringing their hands over oil’s impressive price run-up. Yes, crude oil has more than doubled over the last year, and closed each day this above the psychologically important $80 level.

But there have been plenty of past occasions when stocks have performed admirably in the wake of $80 oil. Why should now be any different?

To use a recent example, consider the three calendar years from 2011 through 2013. Crude oil averaged $96 a barrel over those three years, and yet the S&P 500

SPX,

performed very well, thank you—producing an annualized dividend-adjusted return of 16.2%.

The stock market hasn’t always reacted this well to high oil prices. But my argument is that there is no consistent pattern. That’s why I take exception to those who argue that a high oil price should be bad for stocks.

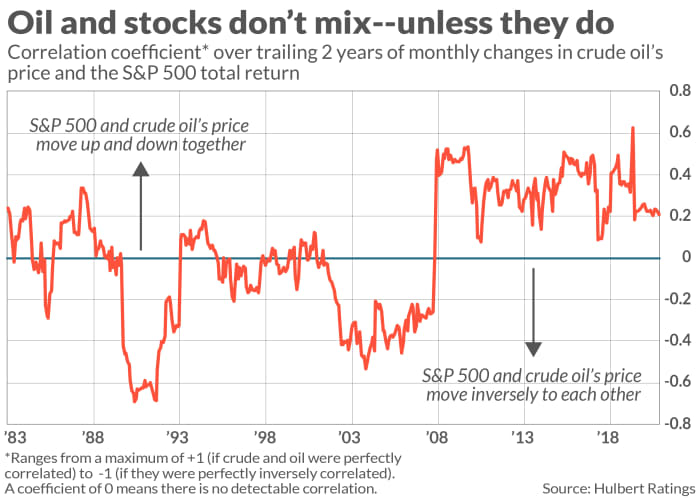

Consider what I found when I measured the extent to which crude oil and the S&P 500 move up and down in tandem. The accompanying chart illustrates what I found; it plots the correlation coefficient of monthly changes over the trailing two-year period. Notice that, over the last four decades, this coefficient has sometimes been above 0.6 (indicating that stock and oil are highly correlated) and at other times has been below minus 0.6 (indicating that the two move inversely to each other, with one tending to zig when the other zags, and vice versa).

What explains this widely varying correlation? No doubt many different factors are playing a role, including sheer random noise. But one big part of the puzzle is investors’ preoccupation. When investors are more preoccupied with an overheated economy and inflation, then higher oil prices tend to be bearish for stocks. But when economic weakness and deflation are their bigger worries, as they have been for several years, a higher oil price is considered good news for equities.

In order to use oil’s price as a leading indicator of the stock market, therefore, you would first need to know what is most on investors’ minds. Complicating matters even more: Investors are fickle, able to change their preoccupations at a moment’s notice.

No wonder that oil’s relationship with the stock market is not straightforward.

Parallels with past studies

My analysis is not the first time researchers have found that the markets’ reaction to economic news is dependent on what investors are most preoccupied with. Consider a classic study, “The Stock Market’s Reaction to Unemployment News: Why Bad News Is Usually Good for Stocks,” which was published in the Journal of Finance in 2005. Its authors are John Boyd, a finance professor at the University of Minnesota; Jian Hu of Moody’s Investors Service; and Ravi Jagannathan, a finance professor at Northwestern University.

The researchers found that when investors’ primary concern is economic weakness, then unexpectedly bad unemployment news causes the stock market to fall. But, during economic expansions, unexpectedly bad news is a good thing because it increases the likelihood that the Federal Reserve will reduce interest rates—or at least not raise them.

The researchers’ study helps us understand why stocks have been as strong as they have been in the wake of higher oil prices. Consider the market’s reaction to the Oct. 8 release of the latest unemployment data: The Labor Department reported that nonfarm payrolls rose by just 194,000 in September, far short of the 500,000 that was the consensus expectation of economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal. The S&P 500 closed down 0.2% for the day, and the Nasdaq Composite fell by 0.5%, suggesting—per the 2005 study—that investors are more preoccupied with economic weakness rather than inflation.

That certainly runs counter to the impression created by the financial media’s headlines, which have become obsessed with the “high inflation is here to stay” theme. But headline writers don’t represent the market.

Still not convinced? Take how the 10-year Treasury yield reacted earlier this week when it was reported on Wednesday morning that the Consumer Price Index in September rose by 0.4% for the month, higher than the 0.3% that economists polled by The Wall Street Journal had expected. Even though that added fuel to the “high inflation is here to stay” theme, the 10-year yield actually fell for the day. That’s not how you would expect bond traders to react if they had become more worried about inflation.

The bottom line: At some point oil’s price could become so high as to sabotage the bull market in stocks. But we won’t know that until after the fact.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t reduce your equity exposure, or increase your allocation to traditional inflation hedges. But, if you want to do either of those things, you will need to justify your decision for other reasons besides oil trading for $80 per barrel.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.