This post was originally published on this site

Old habits don’t fade easily on Wall Street, even those evoking a scandalous chapter for global finance.

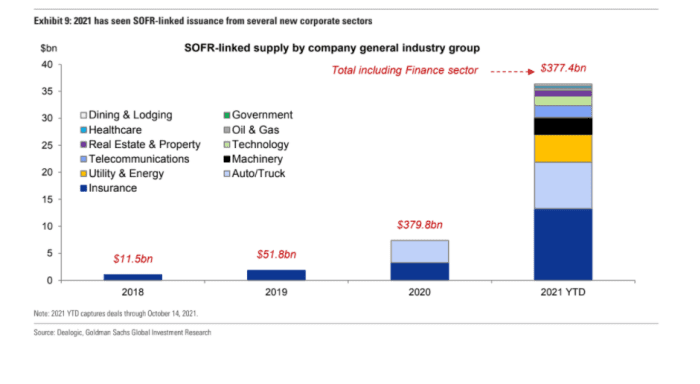

Companies already this year have issued more than $377.4 billion of debt using the new replacement for the scandal-prone London interbank offered rate, LIBOR, putting 2021 on pace for a record, according to a Goldman Sachs report.

Global regulators have been working to discontinue LIBOR, following a global rate-rigging scandal a decade ago that resulted in several large investment banks admitted to manipulating the benchmark.

This chart shows an growing range of companies this year using the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, or SOFR alternative, when arranging debt financing, including auto and truck makers, but also utilities, healthcare and real-estate firms.

SOFR is catching on as a rate alternative

Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Dealogic

The uptake by corporate America has been a promising sign, particularly since three years ago SOFR was being used mostly by financial-related firms on a modest $11.5 billion of debt financing.

On Friday, Bank of America Corp.

BAC,

which like a raft of large banks this week easily beat third-quarter earnings estimates, was in the market with an $3.25 billion corporate financing tied to SOFR.

Regulators have warned banks and corporations for years to pick up the transition pace away from LIBOR, which remains tethered to trillions worth of financial contracts.

Read: Wall Street takes fresh steps to kick $200 trillion Libor debt habit

Promises, challenges

The LIBOR benchmark was created in the late 1980s by a British banking group, but now faces a Dec. 31 deadline when regulators say it can no longer be used on new U.S. financial contracts.

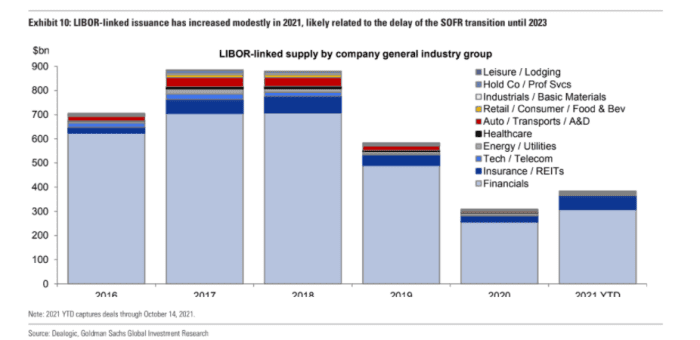

Despite the looming end, Wall Street hasn’t quit LIBOR yet. Goldman’s research team pegged roughly $400 million in new leveraged loans tied to the benchmark this year, a figure that eclipsed 2020 levels.

LIBOR-linked loans on the rise

Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Dealogic

“While there have been a handful of leveraged loan deals this year that reference some form of an alternative LIBOR rate (either immediately, or in the future), the vast majority of the record-setting issuance in the loan market has been

benchmarked to LIBOR,” Goldman’s credit strategy team led by Lotfi Karoui, wrote in a weekly note.

“Similarly, LIBOR-linked debt issuance also continues to grow in the bond market.”

SOFR has been viewed by regulators and many banks as a preferred, more transparent benchmark rate, in part because it is tied to overnight repo transactions.

Even so, it is adoption remains in a fledgling stage in the near $10.6 trillion U.S. corporate bond market, where most debt is tied to fixed-rate Treasurys

TMUBMUSD10Y,

rather than a floating-rate like SOFR.

To help ease the transition, U.S. banking regulators late last year said LIBOR rates will continue to be published until June 2023.

In terms of progress, Isha Chanana, senior research analyst at Income Research + Management, pointed to increased swap trading volumes in SOFR, but also tepid SOFR futures volumes at under 10% of LIBOR and “bouts of sudden and significant short-term dislocations in repo rates,” in a recent research note.

“With SOFR tied to secured, overnight repo transactions, it should be more stable. Right?” Chanana wrote.

However, SOFR traded briefly above 10% intraday in September 2019, but also declined essentially to zero after the Federal Reserve “moved to a zero-interest rate policy” in March 2020, Chanana noted, while pointing out that other benchmarks temporarily rose to reflect credit risks.