This post was originally published on this site

The recent congressional action to raise the debt ceiling is a welcome reprieve, but the issue is expected to re-emerge in early December.

During the recent debate, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen highlighted some of the potential consequences of a failure to raise the debt ceiling. If Treasury could no longer borrow and its cash balance were insufficient for the government to pay its bills, Yellen testified that: “Nearly 50 million seniors could stop receiving Social Security payments or receive them delayed.”

Read: How a ‘self-nudge’ could help you make better money and life decisions

That brings the whole issue into my lane.

Before discussing the mechanics, let me make two comments, both political.

First, the debt limit is a silly provision and should be abolished. It provides no fiscal discipline; those decisions are made at the time an expenditure or tax change is initiated. Instead, the debt limit has been used repeatedly to force a crisis and extract concessions.

Second, whatever the mechanics involving the debt ceiling and Social Security benefits, my bet is that Congress will find some way to ensure that Social Security checks go out on time.

During the debt limit crisis in 1996, when Treasury announced that it didn’t have enough cash to pay March benefits, Congress allowed Treasury to issue enough debt to make the payments by not counting those borrowings against the debt limit.

Read: Are you eligible for Medicare? What to know about open enrollment

In terms of the mechanics, it is not enough to say that Social Security has its own funding source and therefore would not be affected by the debt limit.

Even if Social Security had enough money coming in each year — through payroll taxes and the taxation of Social Security benefits under the federal income tax — to cover promised benefits, its finances are closely tied to Treasury transactions.

Read more about Social Security on MarketWatch

Under normal procedures, Social Security revenues are immediately credited to the Social Security trust fund in the form of short-term, nonmarketable Treasury securities called certificates of indebtedness (CIs). The revenues themselves stay in the General Fund, from which Treasury pays monthly benefits. When Treasury pays the benefits, it redeems some of the CIs. If Treasury does not have enough cash on hand (e.g., because it has used the cash to pay other non-Social Security bills) and is unable to issue new debt because of the debt ceiling, Social Security benefits could be delayed.

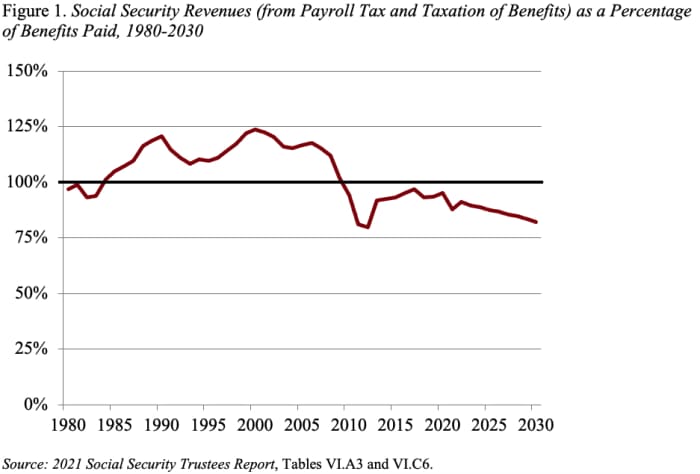

Moreover, as you know, Social Security is currently running a cash deficit each year. That is, its tax revenues are less than 100% of promised benefits (see Figure 1).

That gap between revenues and outlays is currently being met by interest on the trust fund and, as of this year, by drawing down trust fund assets. If Treasury has no cash and is up against the debt ceiling, it will be unable to pay the interest on the special issue obligations held by the trust fund nor will it be able to redeem the obligations.

So yes, the Social Security program has the combination of incoming tax revenues and assets in the trust fund to cover all benefit payments through 2034 (and about three-quarters of promised benefits thereafter), but meeting those payments on a timely basis requires Treasury to have the cash — or access to cash through borrowing — to make those payments from the General Fund. If the debt limit prevents Treasury from issuing new debt to manage its cash flow or to redeem trust fund assets, benefits will not be paid on time.

Most likely, none of that technical stuff will matter. No member of Congress wants to be responsible for millions and millions people not getting their Social Security check. So even if all hell breaks loose, Congress will almost certainly pass legislation to make sure that Social Security checks go out on time.