This post was originally published on this site

In recent years, cities and states across the U.S. have made the decision to rename Columbus Day, a federally designated October holiday, as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. The idea is to support native peoples in general, but also to recognize the fact that Native Americans called this land home long before European explorers laid claim to it.

But the naming issue continues to evoke strong feelings on both sides. And more than a few locales are keeping Columbus Day, set for Oct. 11 this year, as is.

Count Portsmouth, N.H., among them. In June, the city council of this New England burg — population roughly 22,000 — narrowly rejected a proposal to have local residents honor Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Columbus Day together.

Local resident Sue Polidura, a Republican who ran an unsuccessful campaign for the New Hampshire state Senate, was among those who voiced her support for leaving Columbus Day as is.

“I am against renaming things that have been established for a long time,” Polidura told MarketWatch. “You can honor Indigenous people any time you want to.”

Locals who were in favor of recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day were equally adamant, even if their efforts ultimately failed.

“History has made it clear that Columbus and the colonization of Americans has put Indigenous people through a variety of hardships that they are still struggling to escape from,” said Harini Subramanian, a high-school student, in her remarks to the Portsmouth city council a few months ago.

Portsmouth Mayor Rick Becksted, who was among the council members voting against recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day, didn’t respond to a MarketWatch request for comment.

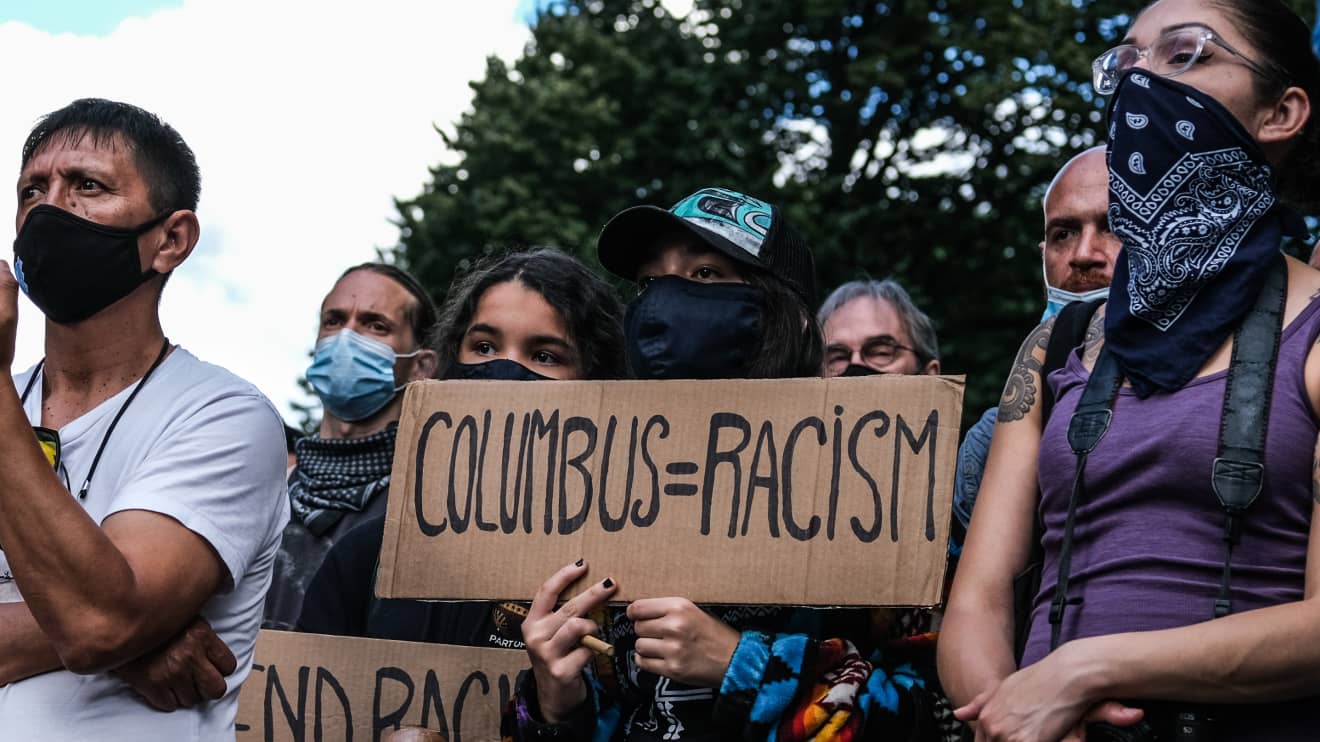

Members of the Indigenous Peoples Day New York City Committee at a June 2020 protest. The group’s long-term goal is to remove the statue of Christopher Columbus at Columbus Circle in Midtown Manhattan and change Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Byron Smith/Getty Images

The movement for recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day is clearly growing, however. In 2021, a number of cities joined the list of those honoring the day, with new adopters including Boston, Tempe, Ariz., and West Lafayette, Ind. More than 10 states have also approved similar naming measures.

The recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day now extends all the way to the White House, with President Joe Biden having just issued a proclamation decreeing the day as one to honor “Indigenous peoples’ resilience and strength.” The president also issued a proclamation recognizing Columbus Day, which still retains its federal status.

Opposition to renaming the holiday has sometimes come from Italian-American groups that see Columbus Day as a way to honor their heritage, similar to how Saint Patrick’s Day has become a celebration of all things Irish.

The contributions of Italian-Americans was a factor cited by Nicholas Isgro, mayor of Waterville, Maine, when he issued a proclamation in 2019 that declared the October holiday would retain its Columbus moniker. In so doing, Isgro was defying the state, which had adopted the Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognition that year.

Isgro, who declined a MarketWatch request for comment, no longer serves as Waterville mayor, having opted not to seek reelection. The city now recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ Day, according to a spokeswoman.

Some locales try to have it both ways. While New York State continues to recognize Columbus Day — former Gov. Andrew Cuomo said any naming change would “insult or diminish the Italian American contribution” to the United States” — New York City’s school system has turned Oct. 11 into a hybrid holiday (and day off). The day is recognized in the school calendar as “Italian Heritage Day/Indigenous Peoples’ Day.”

John E. Echohawk, an attorney who serves as executive director of the Native American Rights Fund, an advocacy group, thinks it’s only a matter of time before Indigenous Peoples’ Day will become more universally recognized.

The logic for the renaming is simple, he said: “Columbus did not discover America. We were here first.”