This post was originally published on this site

U.S. municipalities are increasingly issuing bonds to pay down their accumulated pension obligations, a step akin to “gambling,” according to an analysis out Monday.

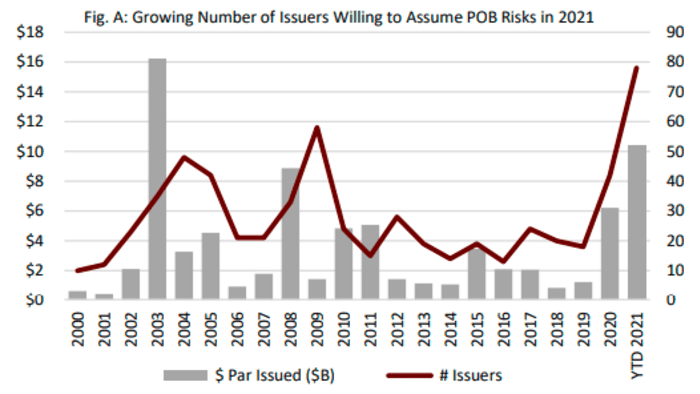

The report, from muni bond market stalwart Municipal Market Analytics, notes that nearly 80 state and local governments have issued such bonds so far in 2021, the most on record back to 2000. The amount issued so far, $10.5 billion, is dwarfed by the roughly $16 billion issued in 2003.

Source: MMA Weekly Outlook

Governments have been enticed to issue the bonds by the strong equity market and continuing low interest rates, although MMA notes both conditions are ripe for change.

Issuing pension obligation bonds is essentially a coin toss, the report points out. If a government uses bond proceeds to make a large lump sum contribution to the pension plan, and pension administrators manage to meet their investment objectives, it’s money well spent.

If that doesn’t happen, however — which is arguably more likely with stock prices

SPX,

at records and the Federal Reserve getting ready to remove monetary accommodation

TMUBMUSD10Y,

— then taxpayers are on the hook for future pension shortfalls as well as debt service on the bonds.

The 80 issuances so far this year have been almost exclusively local governments, but most of those participate in state-wide pension plans, which typically invest at least 70% of their assets in stocks and alternatives, MMA notes.

Beyond the big picture, MMA’s list of reasons to be wary of pension bonds spills onto two pages.

The bonds intensify “credit procyclicality,” the group says. In other words, if pension fund investments underperform because of weak financial market returns, that probably means that the economic backdrop for the local government is also weak. That means the “POB will increase gross liabilities, and annual costs, at the same time other budget challenges grow during a recession.”

Most public-finance experts believe budget discipline is the most important consideration in keeping pension plans healthy. Still, as the report points out, in a severe downturn, a local government might consider moderating a contribution to a pension. Payments to bondholders, on the other hand, aren’t as flexible — and could crowd out payments to other services that taxpayers rightly expect.

“A community comfortable with issuing a massive taxable bond to invest in their future should, at a minimum, consider all the ways those bond proceeds could be invested,” MMA analysts write. “There may well be a better use of proceeds (e.g., neighborhood schools and education funding, small business incubator or job training, creation of a public STEM university) to benefit the local economy and stakeholders and thus long-term growth and tax revenue capacity.”

It’s important to note that some recent scholarship supports the idea that local governments often unnecessarily subordinate immediate taxpayer needs for the long-term health of their pensions. Many public finance guidelines advise a pension plan be able to pay out all necessary benefits to current employees and retirees for 30 years. But some experts now suggest that a pay-as-you-go system like Social Security would work just as well.

See: Public pensions don’t have to be fully funded to be sustainable, paper finds