This post was originally published on this site

Too many of us live life on autopilot, racing from one obligation to another. It may seem like the path to success — but without time to reflect, an ominous possibility looms: What if we’re optimizing for the wrong things? We need to give ourselves the opportunity to explore what a successful life means to us.

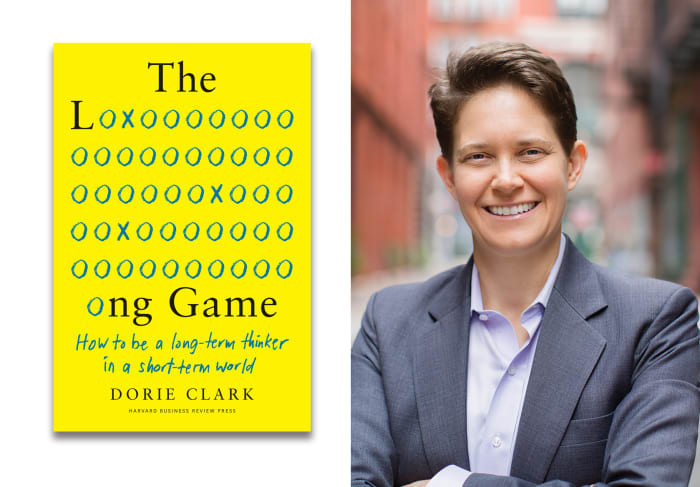

You can’t pour anything more into a glass that’s already full. If we’re going to make smart choices about how to spend our time and energy, as I describe in my new book “The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World,” we need to give ourselves some “white space.”

Few of us have the ability to go on a year-long sabbatical or even to spend hours meditating about our future. But fortunately, as David Allen, author of the acclaimed productivity guide “Getting Things Done,” told me: “You don’t need time to have a good idea. You need space. And you can’t think appropriately if you don’t have space in your head. It takes zero time to have an innovative idea or to make a decision, but if you don’t have psychic space, those things are not necessarily impossible — but they’re suboptimal.”

What’s needed, then, is the resolve to pull ourselves out of the muck and mire of the day-to-day. Here are three ways to do it:

1. Recognize the hidden benefits of busyness: Of course we’re all too busy — no secret about that. Studies have shown the average professional spends 28% of their workday on email and attends 62 meetings per month. It’s hard to get much actual work done in the midst of all that. But that isn’t the full story. It turns out there are emotional benefits to busyness that we need to face up to if we’re going to take the necessary steps to fight back.

One is that it’s often easier, in a situation where we’re unsure what to do (How do I increase sales 30%? Should I quit my job or stay at the company? Is it a good idea to launch that new product line?) to just keep moving forward on your current path. We can tell ourselves we’re too busy to be strategic, but it can often serve as a form of avoidance.

Additionally, at least in the U.S. and many Western countries, busyness conveys high social status — so we may be disincentivized from giving that up, even if we claim we’d like to have a less frenetic schedule. As Silvia Bellezza of Columbia Business School and her colleagues revealed, “by telling others that we are busy and working all the time, we are implicitly suggesting that we are sought after, which enhances our perceived status.”

2. Choose to change our perspective: If we’re culturally predisposed to be impressed by “crazy busy” professionals, we’ll likely need to forcibly reorient our perspective. Author and entrepreneur Derek Sivers provides one useful framework: “I have a very negative impression of the stereotypical frazzled, freaked out, ‘OH MY GOD I’M SO BUSY!’ type,” he says. “They seem out of control — not in control of their life. But I’ve met a few super-successful people that are calm, collected, unbothered, and give you their full attention. They seem to have everything under control. So, I’d rather be like that.”

Instead of automatically and unthinkingly equating busyness with status, we can instead choose what to admire, such as someone having autonomy over their schedule. When we shift our values in the direction of our own aspirations, it makes it easier to navigate in that direction.

3. Plan around your priorities: My friend Dave Crenshaw, a time management expert, works around 30 hours per week and takes every July and December off to vacation with his wife and kids. How does he do it? He didn’t build a frenetic business for himself and then try to jam family time into interstitial moments. Instead, from the beginning, he built systems and structures around the time he planned to spend with them.

“The average person has mountains of inefficiency in their day, things that they put up with and they don’t even realize it, because they’ve given themselves permission to work as long as it takes,” he says. “When you give yourself permission to work long hours, to work continuously, you allow these little systemic, strategic inefficiencies to crop up all over the place.”

Conversely, when you start with parameters like “I’m going to take all of July off,” or “I’m going to finish work by 6 o’clock every night,” it forces creativity in the systems you develop. You can spot inefficiencies — whether it’s a slow-running computer or an awkward scheduling system — because you can’t afford not to. The key is to start asking yourself high-level questions such as:

- Should I be doing this task at all?

- Could I delegate this work to someone else, or stop doing it altogether?

- Where should I focus my effort in order to get the biggest return?

- If I were starting fresh today, would I still choose to invest in this project?

Like a poet deciding to work within the strictures of writing a sonnet, you’re leveraging positive constraints to make you sharper.

Almost no one likes the results of the short-termism we see around us: the relentless frenzy, the endless hamster wheel, the aggressive pursuit of goals that quite possibly aren’t the right ones.

But it takes strength to go against the prevailing culture. Internal strength, because we have to face down uncomfortable questions about who we are and what we really want. External strength, because we have to deal with bosses and colleagues and clients who are still used to measuring productivity through face time and volume.

Harvard Business Review Press

We have to be willing to make choices. And at a basic level, we have to believe change is possible in the first place.

To become a better, sharper, and more strategic thinker, the first step is clearing away the non-essentials. That’s how we create white space and give ourselves room to play the long game.

Dorie Clark is a marketing strategy consultant who teaches at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. This piece is adapted from her new book, “The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World,” (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021). Her free Long Game strategic thinking self-assessment is available at dorieclark.com/thelonggame.