This post was originally published on this site

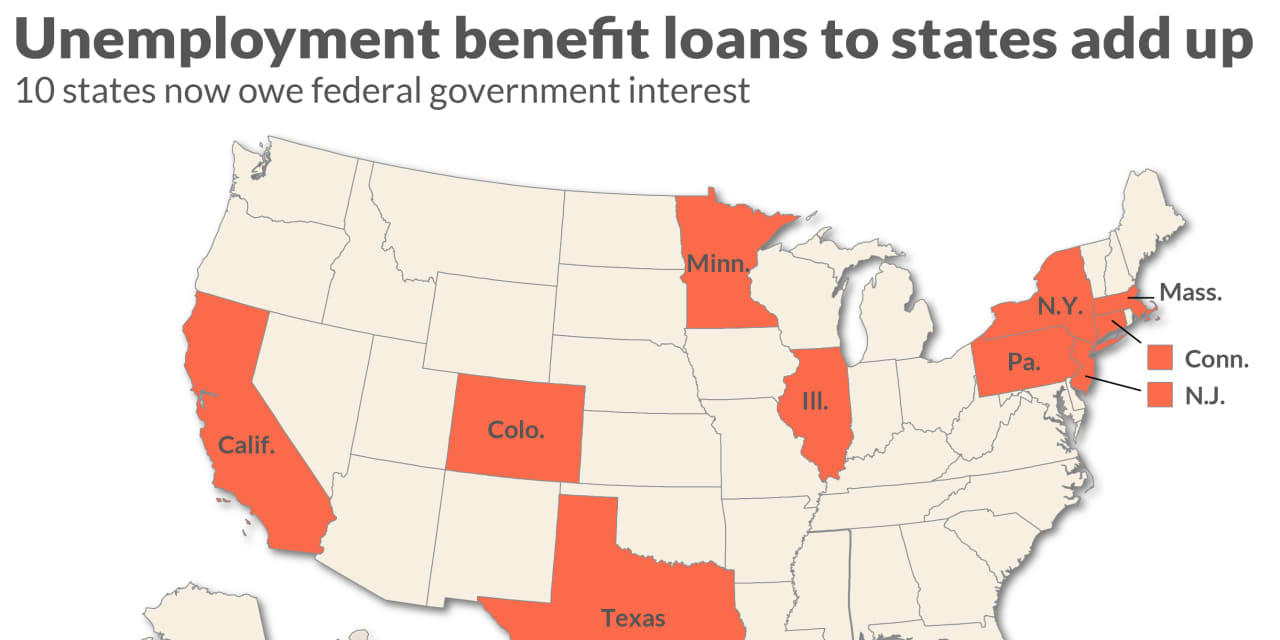

Ten states now need to repay the federal government with interest for money borrowed to pay unemployment benefits during the pandemic downturn. The states, shown on the map above, missed the Sept. 6 deadline to pay back jobless benefit loans, and owe the Treasury Department $45 billion, at an interest rate of 2.28%.

It’s not uncommon for states to borrow from the federal government in severe downturns. In 2009, in the depths of the Great Recession, 36 states owed roughly the same amount that’s owed now, noted Andrew Stettner, a Century Foundation senior fellow.

“There’s a big overlap between the ones that borrowed in 2009 and the ones that are borrowing now,” Stettner told MarketWatch. “Large states in particular have had difficulty maintaining a self-financing system.”

States fund their unemployment insurance trust funds through employer taxes and borrow from Treasury when they’ve run out of money to pay benefits. During the coronavirus recession, Congress extended the grace period before states would start to owe interest on those loans.

“It’s complicated because some states that did not borrow become more financially stable by tweaking the benefits side of the equation,” Stettner said. “They paid out less and were able to maintain their trust funds while keeping taxes low.”

For some states, holding down business taxes tied to unemployment insurance is a priority, even though the annual average is marginal: $277 per employee in 2019, according to Labor Department data.

“This idea that tweaking that tax up to a more responsible rate would be the factor in location decisions, or would hold back hiring, has never held much water,” Stettner said. “No one has ever been able to produce any evidence that states with lower taxes have better employment. States like New York and California generally have pretty good economies.”

Still, he said, some states see it as a competitive advantage to have not just lower taxes, but also limited benefits, so companies based there believe they have access to plentiful labor.

Read next: It’s a ‘race to the bottom’ as states end unemployment benefits too soon, critics say

On the flip side, states that imposed more restrictions throughout the pandemic, like shuttering businesses and limiting in-person gatherings, likely needed to pay out more in jobless benefits.

The American Rescue Plan, passed in March, allows states to use their federal stimulus money to repay the loans. While that conforms with the letter of the law, Stettner said he’s concerned about the spirit of fiscal sustainability — and fairness.

“If you were insolvent after the financial crisis, if you’re insolvent after COVID, well, maybe there’s something more structural going on,” he said. “We’d like to see that (using ARP money) go hand in hand with making some changes. Using stimulus money is a benefit to employers, so maybe there should be something for workers as well.”