This post was originally published on this site

State pension systems finished the 2021 fiscal year in the best shape since the financial crisis, thanks to fiscal discipline and the best market gains in 30 years, according to an analysis out Tuesday.

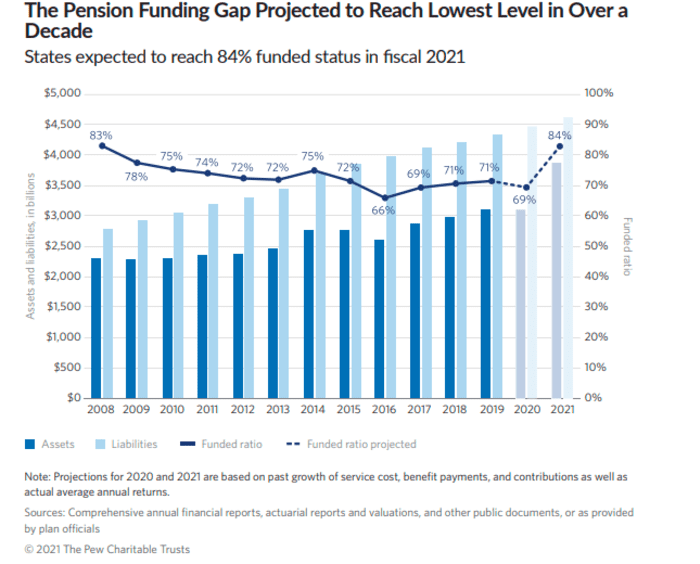

Retirement systems earned estimated returns of over 25%, according to the report, from the Pew Charitable Trusts. That pushed aggregate funding levels over the 80% threshold that’s often considered a marker of sustainability for the first time since 2008. In fact, Pew projects funding to be 84%, a big jump from 71% in 2019.

That year, plans recorded a funding shortfall — the difference between the total value of pension benefits owed to current and retired employees and the plan assets on hand — of $1.25 trillion. For the 2021 fiscal year, which ends June 30, Pew estimates that gap to be less than $1 trillion.

Earlier coverage: Public pension funding topped key threshold on stock-market gains

Employer kick-in helps close gap

Market gains weren’t the only contributor to stronger funding ratios. Employers have consistently boosted their contributions over the past decade.

“As a result, after decades of underfunding and market losses from risky investment strategies, for the first time this century states are expected to have collectively achieved positive amortization in 2020, meaning that payments into state pension funds were sufficient to pay for current benefits as well as reduce pension debt,” the report notes.

Politicians have often used economic downturns as an opportunity to lower pension contributions, but they didn’t in 2020. That’s probably thanks to a years-long shift in budget priorities, the report points out, “and a recognition that the costs of postponing obligations are untenable if left unaddressed.”

The report also notes that successful state pension systems are able to maintain high funding ratios “in part because they have strategies—including policies that target debt reduction and share gains and losses with workers and retirees—to mitigate cost increases during economic downturns.”

It’s important to note that some recent scholarship suggests public pension systems need not aim to be 100% funded. Just as the Social Security program relies on a pay-as-you-go approach, state and local retirement plans might do the same.

Budget tradeoffs

As the Pew report says, prioritizing better funding of state pensions comes at a cost: “it has also crowded out spending on other important programs and services and left states with less budgetary space to sustain future rises in pension payments.”

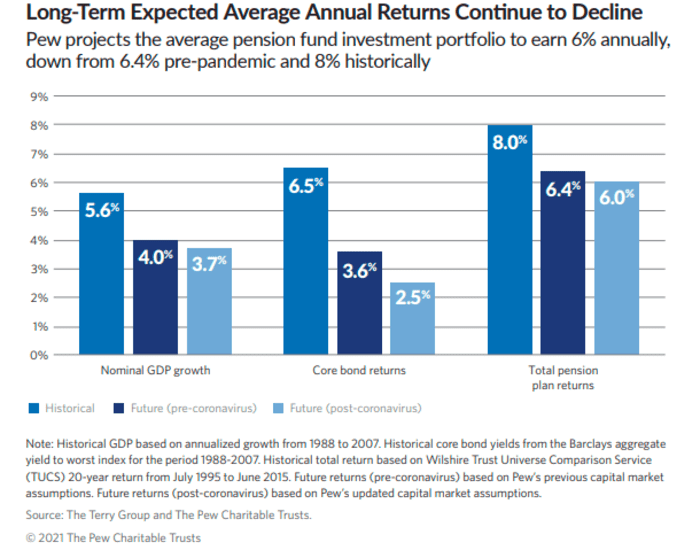

That’s important because investments are likely to return less in the future. The report cites projections of returns for stocks

SPX,

which generally make up about half of pension portfolios, to be 6.4% over the long term, and projections for bonds

AGG,

to yield just 2% over the next decade. Bonds typically make up about one-quarter of public pension assets.

Read next: These public pension systems used to have too much money. Now they’re in crisis. What happened?